58th Venice Biennale: May You Live In Interesting Times

Rugile Barzdziukaite, Vaiva Grainyte, and Lina Lapelyte, Sun & Sea (Marina) (2019). Opera-performance. Exhibition view: Lithuanian Pavilion, May You Live In Interesting Times, The 58th International Art Exhibition – la Biennale di Venezia (11 May–24 November 2019). Photo: © Andrej Vasilenko.

The 58th Venice Biennale, May You Live In Interesting Times (11 May–24 November 2019), certainly benefitted from low expectations, given the lacklustre curatorial of the previous edition, when different segments of the show were conceptually framed with titles like 'Pavilion of Joys and Fears' and 'Pavilion of Colours'. Add to this the disappointing (but not surprising) Golden Lion awarded to Anne Imhof's installation for the German Pavilion, Faust, which featured the nation-state as a fashion-forward Berlin night club (call it Berghain for the art world), and it felt like things could not get any worse. Thankfully, they didn't.

Not only did artistic director Ralph Rugoff inject a fresh approach to curating the central show by presenting most of the 79 participating artists in both the Giardini and Arsenale exhibition spaces, but the award of the Golden Lion for best National participation to Lithuania demonstrated how it is possible to be both socially relevant while pulling off one of the most likeable national pavilions in recent memory. From a rectangular balcony overlooking a covered courtyard, viewers gaze down at Rugilė Barzdžiukaitė, Vaiva Grainytė, and Lina Lapelytė's performance-installation Sun & Sea (Marina) (2019), curated by Lucia Pietroiusti, which completely transformed the pavilion's historic building into an artificial beach. With sand, light, heat, towels, umbrellas and, most importantly, tens of rotating performers dressed in beachwear enacting their day in the sun, many singing operatically, what powered this exhibit was its knowing fakeness—a nod to a future when beaches have been replaced by their imitations.

At the Arsenale, Rugoff has consciously avoided over-curation by providing each artist abundant space, thus presenting a group of loosely related but singular artistic positions distinguishable from each other. Viewers can casually ignore the Arsenale's long and cumbersome hallway and rustic surfaces, thanks to the breaking up of the space with a generous supply of raw plywood and white walls, which admittedly led some critics to compare the exhibition with an art fair. Even if true, the effect—as one curator observed—is more like the Untitled section of Art Basel than your basic grid of commercial booths.

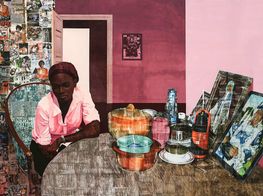

In fact, Rugoff's curatorial approach seems to reveal a genuine interest in contemporary painting and sculpture, which was made apparent from his careful consideration of painters and sculptors in the show. Highlights include Njideka Akunyili Crosby's paintings at both venues of the central exhibition: large canvases depicting the interiors of Nigerian homes at the Giardini, which invoke the saturated colours, texture, and flatness of digital screens, and a series of portraits in the Arsenale utilising monochromatic backgrounds with greyscale figures that seem to function as a missing link between classic black-and-white portrait photography and digital selfies. In terms of sculpture, Nairy Baghramian stood out with Maintainers (2019) in the Giardini, a series of weirdly shaped pieces of cork and Styrofoam covered in coloured paraffin wax resembling natural forms interconnected with pieces of aluminium—a clarifying step forward for a discipline that has been suffering from an identity crisis due to its conflation with all other forms of three-dimensional art.

It is true that Rugoff's exhibition lacks a main curatorial focus—works on show address a plethora of questions around class struggle, war machines, racial equality, climate catastrophe, artificial intelligence, language and its politics, not to mention migration and borders. By showing artists who have different concerns without framing them within a set curatorial direction, Rugoff seems to be advocating for art in general by allowing for broader conversations to occur among practices. In other words, if the works in the exhibition raise social issues, it is not because of the curator's focus but as a consequence of artists and the themes they tackle.

Take Slavs and Tatars' installation, Dillio Plaza (2019), which acts as a bold full stop for the entire show at the Arsenale. Located in a large and enclosed square-shaped space at the end of the venue, a central fountain in a tiled square pool is located among other elements, from a vending machine selling sauerkraut juice to scattered green plastic garden chairs for visitors' use. Hanging in the space is a tall, thick vinyl curtain printed with the image of two cucumbers, each adorned with an oversized pink nipple—a suggestive and playful image that connects with the collective's wall installation of signs at the Giardini, Tranny Tease (pour Marcel), (2009–2016), which expresses a similar sense of play when it comes to how the artists mix and match the pronunciation of words and their different meanings across languages in visual terms. As a whole, the project explores the political implications of transliterations, mistranslations, and semantic transformations 'as a strategy of resistance, and research, into notions such as identity, colonialism, and faith.'

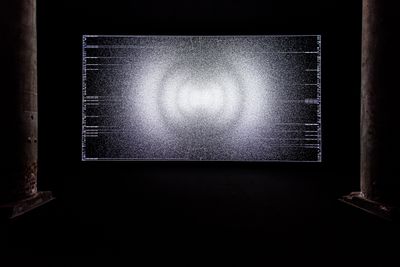

Unfortunately, with its stubborn floor plan, the architecture of the Central Pavilion at the Giardini was clearly an obstacle to Rugoff's curatorial efforts when compared to his remodelling of the Arsenale's spaces. That said, successful installations include Ryoji Ikeda's spectra III (2008/2019), an all-white hallway overexposed with powerful white fluorescent lights covering the ceiling, which contrasts with the artist's projection theatre in the Arsenale, where Ikeda's monumental three-part single-channel installation, Data-verse (2019), is installed behind a pair of dominating architectural columns. This time-based collage consists of computer-generated images and soundtracks produced from open source scientific data sets from institutions like CERN and NASA: a poetic index of the increasing complexity with which artificial and automated intelligence understand and interpret the natural and social worlds.

When viewed in relation to the bright, white hallway that Ikeda created at the Giardini, the impact of the machine-driven epistemological revolution on humanity's understanding of the world reflected in Data-verse could well amount to incapacitation by the blinding light of technology, as depicted in spectra III.

Lawrence Abu Hamdan's film installation Walled Unwalled (2018) at the Giardini, and his eight related video loops shown at Arsenale, This Time There Were No land Mines (2017), similarly present a contemporary contradiction when it comes to technology as an instrument of power. The former work explores various legal cases that were resolved with acoustic evidence heard through walls, while the latter installation focuses on an uprising of Palestinian residents at the Golan Heights on both sides of the border between Syria and Israel on 15 May 2011. Both works point to how, in today's complex technopolitical world, new technologies, while bringing down old walls and borders, are at the same time helping to erect new divisions.

Further demonstrating the rich network of positions and counter-positions on display in the Biennale's central show are works by Arthur Jafa, who was awarded the Golden Lion for best artist in the central exhibition. Screening at the Giardini is The White Album (2018): a video collage of footage drawn from numerous sources—including YouTube clips, music videos, and footage from historical archives—that combine to offer a stark portrait of the pathologies of whiteness. (Scenes include CCTV footage of Dylann Roof walking into Emanuel African Methodist Church in Charleston, poised to commit a mass shooting.) Jafa's piece deals with questions of race and class in the United States without falling into the trap of identity politics, by focusing on whiteness as a condition. The abstract realism of this jarring work is echoed in the form of three giant logging truck tyres wrapped in chains showing in the Arsenale—anti-monuments to a violence that permeates modern life.

As far as national participations are concerned, a format that is rapidly losing its relevance in the context of global art practice, the Ghana Pavilion, is among a few exciting contributions. Designed by architect David Adjaye into several curved spaces inspired by the nation's architectural traditions, the first gallery presents three lush hanging curtains by El Anatsui made from materials including discarded bottle-caps, aluminium printing plates, and copper wire, alongside Ibrahim Mahama's gorgeously installed A Straight Line Through the Carcass of History 1649 (2016–2019), which blends beautifully with the rough and earthy texture of the pavilion's architecture. This carved wall sculpture made out of salvaged wood, smoked fish mesh, and other found materials represents the resources and industries on which Ghana's political economy has long depended.

On view in the pavilion's other galleries are black and white studio portraits by nationally celebrated photographer Felicia Ansah Abban, Selasi Awusi Sosu's Glass Factory II (2019), a three-channel sound video installation with glass bottles that reconstructs Ghana's bottle manufacturing industry, and John Akomfrah's multi-channel film The Elephant in the Room – Four Nocturnes (2019), which mixes detailed and colourful footage of African flora and fauna with archival photographs of the continent's colonisers. Particularly noteworthy are the nine richly painted canvasses of Africans by Lynette Yiadom-Boakye in rather unusual poses. In one of the most striking images, the skin and dark clothes of a group of young African men are contrasted with the white cigarettes they are smoking.

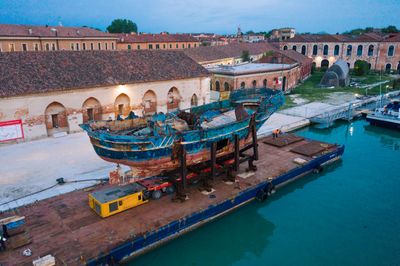

Another strong national intervention has to be the Polish Pavilion's, where Roman Stańczak's installation Flight (2019) references the Smolensk presidential airplane crash in 2010, which killed some of the country's most senior military figures, its central bank chief, a number of MPs, and then-president Lech Kaczyński and his wife.

Using this seismic event as a point of departure, the installation addresses the state of Poland since the collapse of communism more broadly, by showing a scale model of a private plane turned inside out, with its internal parts hung haphazardly on its outer surface. The work ignites both a desire for transparency surrounding the event that the work references—the plane crashed mysteriously in Russia minutes after taking off—and a proper understanding of its political aftermath: an artistic testament to a complex history that must not only be remembered or memorialised, but investigated and confronted.

Flight is an interesting counterpoint to Christoph Büchel's Barca Nostra (2018–2019), the Venice Biennale's most controversial work. From a NATO base in Sicily, the artist transported a boat that sank in the Mediterranean Sea in 2015 and resulted in the deaths of hundreds of migrants, and docked it next to a Biennale café. During the preview week, the gesture drew sharp criticism as a crass and disrespectful affront to the memory of those who perished in a tragic sinking, especially when surrounded by the social circus of the Venice Biennale's vernissage.

Sometimes, concentrated and brief gatherings like the Venice Biennale's opening week can create a hyper consensus that does not allow enough space and time for deeper and more reflective engagements with the subject. Understandably, the sight of visitors taking selfies with an Aperol Spritz in hand around a gigantic rusty boat that represents an ongoing humanitarian crisis—located just a few miles away from docked multi-million-dollar yachts belonging to rich collectors—was appalling, and made those who knew the origins of the vessel uncomfortable. But since when is art supposed to be fully digestible and compatible with our attitudes and conceits, particularly when art is often presented—in events like these—as a political force?

Considering Rugoff's exhibition statement that 'art is more than a document of its time', Büchel's Barca Nostra could easily be considered nothing more than a gigantic three-dimensional document, but the impact of exhibiting such an object goes beyond merely representing a humanitarian and political catastrophe. The boat's inclusion in this year's main exhibition has already opened up several conversations about the way art frames social and political issues and how curatorial exhibitions ought to consider the consequences of such framing. In a way, the gesture invoked Umberto Eco's text 'Open Work', quoted by Rugoff in his curatorial statement, which introduces the author's conception of art as a means to relentlessly test cultural norms. In the case of this edition of the Venice Biennale, the test involves the feedback loop of holding a mirror up to the spectacle. —[O]