Shawanda Corbett: 'Ultimately, it's about world-building'

Shawanda Corbett. Courtesy the artist.

Shawanda Corbett. Courtesy the artist.

Shawanda Corbett embeds her personal origins in New York and Mississippi within a diverse artistic practice that encompasses sculpture, painting, performance, and photography.

The artist, born in 1989 and currently based in the United Kingdom, weaves passionate interests in music and literature into a complexly reimagined lineage of Black American history, traced from its abhorrent roots in slavery through to contemporary life.

Following solo projects at London's NOW Gallery (22 October 2020), Corvi-Mora (16 June–31 July 2020), and Serpentine Galleries (26 July 2019), Corbett made her stateside debut at Salon 94 in New York (19 January–5 March 2022) with an expressive showing of ceramic vessels and paintings that allude to the people and places that she has encountered in life.

Titled To the Fields of Lilac in reference to a song once sung along the Underground Railroad, the exhibition situates lustrous stoneware sculptures on plinths that break up the room into nonlinear blocks of space.

The objects, emblazoned with varying streaks of vibrant and metallic hues, are defined by curvatures formed by the clay's organic encounters with the artist's body—in this way, becoming a metaphysical extension of Corbett, who was born with one arm.

Inspired as much by ceramic traditions from Africa and Asia as they are by the dynamic fluidity of jazz music, Corbett's sculptures intend to encapsulate individual personas and characters—many of whom are routinely stereotyped in politics and mainstream media.

These vertical mounds appear both enigmatic and dignified, each distinguished by its own set of idiosyncratic indentations and markings. Titled after phrases that allude to the vernacular culture of the communities where Corbett came of age, each sculpture emblemises a distinctly Black heritage, signalling admiration through the replication of everyday speech.

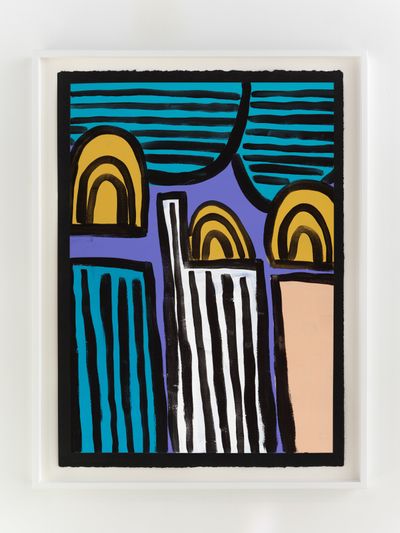

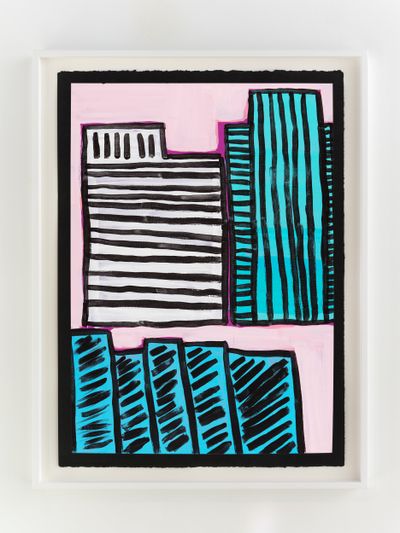

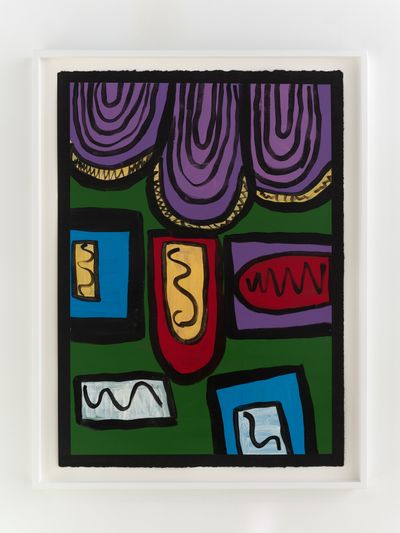

Corbett's subjective history similarly takes centre stage within the suite of paintings that surrounds the sculptures. Bold, black lines demarcate bright blocks of colour from one another, forming graphic shapes that suggest architectural and outdoor spaces.

Strokes within these colour fields, sinuous at times and straight at others, evoke sound by resembling the notations of a musical score. Although their meanings remain elusive to viewers, the paintings suggest a rich narrative of belonging and observation, collectively portraying the world as the artist sees and remembers it.

On a long wall besides these works, a close-up photograph of the artist, printed at larger-than-life scale, commands attention. Corbett, appearing as an invented character that frequents her live performances, gazes into the camera lens, as though to confront viewers and her own creations.

White porcelain clay is smeared onto her face, gesturing towards mime ministry—a religious tradition linked to Black parishes in the United States. Whereas mime ministry actors use bodily movements to convey biblical messages, Corbett, through her alter ego, injects her presence into the exhibition to express a profoundly intimate point of view.

Soon after the opening of the exhibition, the artist reflected on the inspirations and processes behind her practice, and looks to forthcoming projects, including a solo exhibition at Tate Britain in London later this year.

VCHow did your childhood and coming-of-age in New York and Mississippi shape your thinking, both in terms of art and the world at large?

SCIn New York, there was a lot of audio and visual expression. My family lived in predominantly Dominican and Puerto Rican neighbourhoods, where I interacted with different people and experienced different cultures.

In the south, on the Gulf Coast, it was different because the demographic was mostly Black. It was more conversational, and the talking was very performative. It was a way of release. It influenced the music I listen to, what I make, and how I make it.

VCDonna J. Haraway's 'A Cyborg Manifesto' (1985) is often described as a guiding source of inspiration within your practice. Can you reflect on your initial engagement with this text, and talk about how it translates or manifests in your work?

SCScience fiction has always been a part of my interests. I love different streams of reality—how they can communicate different perspectives and outcomes.

I got into cyborg theory after reading 'A Cyborg Manifesto'. I loved the terminology, which was used to describe, essentially, upper middle class white feminism. That isn't a bad thing, but I wanted to add more common terminology and my own perspective—the different identities that I have.

Everyone I encounter, everyone I have met or heard, becomes part of the work.

Cyborg theory is in all my work; in the entire ceramics process, and even with how audiences are positioned. There's a concept in cyborg theory called double vision: you see things twice, from where you're situated and from wherever the camera is.

It can refer to many things, but I understand it as an extension of what you initially see and how you remember it. That makes up a part of the foundation of my practice.

VCCeramics is one of the oldest art forms in the world, whereas cyborg theory and science fiction feel very rooted in the future. Instinctively, they make me think of newer, more technological mediums such as V.R. or A.I. What is it about ceramics that compels you?

SCCeramics is very physical. What I initially liked about it was that I couldn't throw at all. At the very beginning, it would literally fly off the wheel. It gave me a physical challenge.

The wheel records how you move, and you're connected, grounded. I don't want to say primal, but you know what I mean?

A.I. is similar for me. You become the coder telling this machine to do something, and it draws from your knowledge and how you see things. The only thing is that you can't go backwards after the firing, so ceramics is more permanent than A.I.

VCIn your sculptures and paintings, individuals and places that hold particular meaning in your life are reduced to abstract forms and patterns. Do these configurations come about organically, or do they delineate from certain cultures or moments in history?

SCThe technical aspect is influenced by West African and Japanese pottery. The American way of throwing is not necessarily about getting it right, but about altering the clay. You learn to knock the memory out of the clay, because clay has memory.

You are working against the clay the entire way. In other cultures, you are working alongside the clay, even if you are shaping it. It will still do what it does, and that is completely fine.

I would say it is music—like the way jazz musicians play—that influences me more. I'll have an initial image, and it almost never comes out the same way.

I don't really plan that much because, ultimately, it's about world-building. The building takes years, even decades, to capture the entire storyline, which is different from how most artists work. Everyone I encounter, everyone I have met or heard, becomes part of the work.

VCWould you say that your sculptures and paintings, as a cumulative body of work, tell the story of your life?

SCYes and no. I use my background to interpret what is happening, but the outcome is inevitably about a world that doesn't exist.

What does it look like? It addresses the range of humanity, using the traditional science fiction method of going about it. I think it's all connected. The work stems from places that are grounded in some type of reality.

VCIn the current Salon 94 exhibition and in past shows, the works on view all bear titles that draw from expressions, such as Stop all that slouching, boy or Baptize you in the name (both 2021). Are these phrases conceptually united in any way?

SCThe titles are selected during the process of making the work, even when I have to take a break to think about it. They're intuitive, but the phrases come from conversations that I've heard or have had.

The religious references do not allude to age, but experience. There are wise, elderly women, and some men, who go to church and all of that, but there's also a saying that everybody has at least one old fool. The things they would say, while still being insightful, are just delivered differently.

So, it doesn't matter how eloquently words are put together in a sentence, it's all about getting that message. It's a different dialect, for sure.

VCYou've mentioned music a couple of times, which not only influences your painting and sculpting practice but is also a major component of your live performance work. Do you approach performance any differently than how you approach other mediums?

SCIt's all the same. Each medium calls for a different process, but ultimately it all starts with the space, which determines how I make my work. If it's a performance, there's a way that I want audiences to see, to hear.

I use my background to interpret what is happening, but the outcome is inevitably about a world that doesn't exist.

For exhibitions, it's about the flow of walking around, and about being still. There will be parts that draw you to stay put, and parts that prompt you to move around because there is visual overlapping with bright colours.

I respond to the space with music, whether it's a selection or something that is written out. That tells me what the performance is going to look like, how the audience is going to sit, how the dancers are going to be moving. It's complex, so it varies.

VCI've read that you often collaborate with your brother, Albert Corbett. Is that something that you've always done since you were kids? What is that like?

SCIt's cool because we are different sides of the same coin. He's a professional dancer. One of the main reasons why I wanted to work with him is because I am most comfortable with him.

When we think about dance, we think about how the body is supposed to be 'complete'. It's technically complete in my case, but it's different. It's about the language.

While the choreographers I have seen are great, they also have limited imaginations when they meet someone like me—as my brother would say, 'limited resources'.

We have debates together, deep conversations. While he did not choreograph the last performance I did, called Breathe (2020), we still had a conversation about it. What is the breath? How do you capture it? How is it recorded within the Black body?

It was very insightful because he has a photographic memory. He has a lot of what I would call receipts, because he can pull any information from a time in history. We balance each other out, as far as imagination and reality goes.

VCCan you tell us about the white clay that often appears on your face, in photographs, and in performances? Where does that come from, or what does it signify?

SCI created a character, and its name is haar wese, which is Afrikaans for 'her being'. It only shows up when it has something to say, whether it's musically or even visually. The clay on its face is a reference to mime ministry in the United States, in predominately Black churches.

Mime ministry is an original dance—from before ballet was created—performed to gospel music because most of the public did not know how to read.

It was not exclusive to the United States, but it was used to portray a story physically. It's not just about miming the words—performers mime the ad-libs, the breaths, everything. You're not really listening to the church songs so much as you're watching what they're doing.

These mimes apply white makeup on their faces to symbolise their African heritage rooted in slavery. How thick or thin it is depends on how vulnerable the character is going to be.

The first show Body Vessel Clay (29 January–24 April 2022), curated by Dr. Jareh Das at Two Temple Place in London, is great because many astounding ceramic artists, like Magdalene Odundo, will be included. I'm really excited about that.

VCYou're also having a solo exhibition at Tate Britain. Can you talk a bit about these upcoming projects, and what you're planning to show?

SCThe other show, for Tate, is a film based on dance theatre, influenced by Oskar Schlemmer's ballets. Although his work is very political, social, and quite heavy, you don't get a sense of it because of the bright colours. It's definitely its own language.

My version follows 24 hours with a person of colour, in blocks of three hours, for the entire day. It depicts a range of emotions, from the moment you wake up to the moment you go to bed. That's what I wanted to focus on, because we all are connected by emotion.

It's how you express emotion that gives it purpose. It's not about being sad, angry, happy; it's really about love and hate, and the grey areas in-between. It's about self-love, and how you connect with other people who are struggling with self-love. It's deep.

I wrote the music score for the film, found amazing musicians, and it's being choreographed by Albert. There's also a nice display, and ceramics will be involved. It's all in the making. I'm excited about this year, and to see how everything will come together. —[O]