Thomas J Price: Reframing Classical Sculpture

Thomas J Price. Courtesy the artist.

Thomas J Price. Courtesy the artist.

When the London-born artist Thomas J Price graduated with a Bachelor of Fine Arts from Chelsea College of Arts in 2004, the school's college art prize was by no means his most notable accomplishment as an emerging artist.

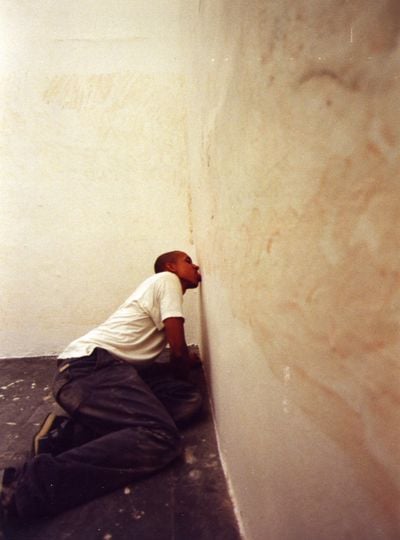

In 2001, Price presented his much-talked-about work Licked, a daring performance, later profiled on the BBC 4 television documentary Where Is Modern Art Now? (2009), in which he licked an entire gallery wall over three days. In the years following his MFA at the Royal College of Art, Price made a dramatic turn, eschewing the grandness and shock value to which he owed his early notoriety. Instead, he opted to cultivate a figurative sculptural practice of subtle variation, as he moved in deliberately slow and considered increments.

Much of Price's earlier work was directly concerned with unconscious forms of communication—from small eye movements in animations such as the series 'Man' (2012) to subliminal messages in his video Hidden People (2000/2001). From these initial preoccupations, Price developed an interest in the minutiae of human facial expression, posture, and comportment—alongside an ardent commitment to material and finish.

From applying palladium or gold leaf to acrylic or aluminium composites, to combining cast bronze figures with colourful Perspex bases, Price continues to uncover the haptic and semiotic depths of this growing range of mediums—using a range of techniques from gilding and lost-wax processes to more contemporary methods like 3D printing. His sculpted figures comprise features from several persons, synthesised into composite characters who look past us with impassive expressions that belie the complexity of human psychology and all the neural activity—like the arrhythmic firing of our synapses—that Price visualised in his earlier moving-image work.

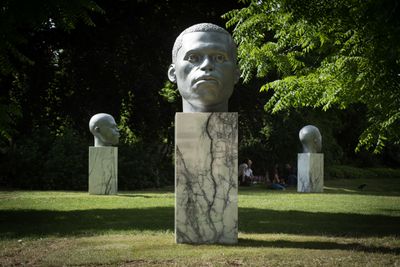

For Price's forthcoming exhibition at The Power Plant Contemporary Art Gallery in Toronto, Ordinary Men (22 June–2 September 2019), a suite of sculptures are presented both inside and outside the gallery. Among them will be a trio of newly commissioned sculptures exhibited alongside smaller bronze pieces and photographs that address the misrepresentations and absences of Black bodies within the traditions of classical sculpture. Showing in Canada Square is Price's 'Numen' series (2016), which embodies the artist's long-standing preoccupation with Greek, Roman, and Egyptian mythology, while on the South Terrace his second monumental cast-bronze, titled Cover Up (The Reveal) (2019), will stand at nine feet in height.

In this conversation, Price reflects on the role of the Black male body, classical statuary, and religious iconography in his work—and the variety of mediums and techniques through which an evolving set of concerns and interests have been articulated in his practice over the years.

TJMWhat were some formative experiences you had during, or just after, your years at art school?

TPI was lucky because my year groups at both Chelsea College of Arts and the Royal College of Art were really ambitious. We had the Young British Artists (YBAs) not far ahead of us and they were, to us, the height of success. This was before the financial crisis of 2008 and we thought we were going to be doing whatever we wanted and realising all the projects we wanted to as artists. But then the crash hit not long after we left art school. I remember presenting work at the Chicago Art Fair in 2008 and it was so quiet. The recession had hit the art world, which was supposed to be untouchable. I remember the experience being quite a surreal one and thinking: 'So this is it? This is how the real world works?' And that was my first experience of the highs and lows of being an artist.

TJMIn those earlier days, amidst the chaos of an economic downturn and the anxiety of influence wrought by the YBAs, did you have a clear sense of the kind of artist you wanted to be and the work you wanted to make?

TPI always knew I wanted to do something long term; I didn't want to skyrocket too quickly and come down with a crash just as fast, which happens a lot. I wanted to build a good foundation that would help me develop ideas. I would call my work 'consistent'. From early on I really tried to concentrate and push through what was happening around me, artistically, at the time. Now figurative work is accepted, and you have quite a few Black artists claiming space and asserting their presence.

When I started making figurative work back in art school, it wasn't really being taken as seriously. I was using stop-motion animation, which no one around me was really doing either. My tutors questioned why I was working in this way because they were reacting against their tutors who had made figurative work. Most people were either working towards a take on minimalism or producing irreverent, YBA-inspired one-liners. And here I was, making a tiny sculpture of a Black person's head that looked like a Roman bust, and I was showing it to a predominantly white audience. What many didn't pick up on was that these were fictionalised people. At that time, I wasn't yet able to express my ideas so well verbally, since I was only just discovering this way of working myself.

TJMIn what ways would you say the responses to your work have changed between then and now—and how have you, in turn, responded to this reception through subsequent work?

TPIn 2016, I had a show at the National Portrait Gallery titled Now You See Me. Previously, I would have been afraid to use that title or to stand behind the aspects of my work that I addressed in that show: ideas relating to race and social status as well as universal human traits. Initially, the work I did was about manifesting oneself emotionally and finding one's place in the world on an intimate level. I then started using different physiognomies, different figure types, and through receiving certain pointed comments and feedback about the characters' race, I became more interested in what happens if I use this kind of person as opposed to another. The only thing that stayed more or less consistent was they were men. Men have often been depicted as strong, authoritative, and resolved, historically, and I always wanted to reveal the inner workings of their emotional worlds.

I showed my first animation, which is based on a gallerist, a white man, whom I had observed in an office that adjoined the corridor behind the downstairs gallery where I had been working as a waiter. I saw him on the top floor—he was incredibly confident, really 'out there,' and exuding power, which went perfectly with the gallery's image. One day, he got off the phone in his office and I could see him staring out into space. It looked to me like the image of someone living two lives: on one hand, projecting an image of unflappable confidence, and on the other, someone who was in some way conflicted. So I tried to recreate this encounter through stop-motion animation.

Then I made another stop-motion work: this time of a Black guy I'd seen on the bus eating or something. There was a real gentleness to him and I was trying to translate this into animation but the most common response I received related to his Blackness. In my naivety—I was in my early twenties then—I tried to defend the work and to answer those questions instead of just asking 'why not?' or 'why shouldn't he be Black?'

TJMAnd what was it in those moments that you saw and were trying to distil with your stop-motion animation?

TPI call them 'in-between' moments—genuine moments when you're not smiling for someone or particularly conscious of how you're presenting yourself. Most of us have our guard up and occasionally it slips a little now and then. I think I became an artist in order to articulate these experiences. When I look back at the early work and how I was approaching these experiences, I can see how my life was absorbed into the work. It was me trying to navigate, without necessarily knowing how, a world that was seeing me in a particular way. That's why I introduced many different kinds of people into the work, to ask: 'What's this person like?' 'How would this person see things?'

For years I doggedly tried to remove race from my work; the first sculptures I made were called Head 1 and Head 2 (2004). I was noticing how, in the media, Black was largely being used in negative contexts; but if, say, someone won an Olympic medal for something, they would just be British. So a lot of the work I make is a reframing of, and response to, the history of racialisation and how it impacts people's experiences of the world—my own included.

TJMCould you tell us about the forms and formats that you work with in your compositions, and why?

TPI've started using 3D-printed models, which is a new way of working for me. I'm looking at the standardisation of how state or imperial power has been visualised in these portraits of men—because they are mostly men—of rank represented throughout Euro-American art history. I'm approaching these Euro-American forms in the same way Picasso approached African masks and Iberian sculpture, for example—with little reverence towards their origins but more of an interest in the aesthetic. If I like the effect, I use it. But there will be a tension in the work because the viewer has likely never seen the kind of person I'm depicting presented in that way.

I also reject some conventions—for example, the figures may slouch a bit, or their expression might not be overtly regal or stately. New Drape (Shakespeare Road) (2011) is a sculpture, in black bronze, of a younger guy whose got his hands in his pockets and is wearing a pair of trainers. In the hierarchy of materials, historically, bronze says 'powerful' and 'official'—it says the person represented has done something to warrant immortalisation in this material. But my figures are 'made up' as a critique of this tradition. It's a way of trying to talk about things in the abstract or a general sense. This made-up person has not had to achieve something, and this is a way of pointing to the intrinsic worth that everyone has as a human. New Drape (Shakespeare Road) (2011) and Man on a Horse (Kings Avenue) (2011) are from a show in 2011 called Angell Town at Hales Gallery, which I named after an estate in Brixton, right next to where I grew up.

When I made What Next (Angell Road) (2011) and Sportswear (Achilles Street) (2011), I wanted to make figures that took up space, that were just present and caught in those in-between moments that I mentioned previously. They may appear a little less-than-happy, or they might be deep in thought, thinking about their shopping list or some other mundane detail. Sportswear (Achilles Street) (2011) is named after a street near my studio—it's a sculpture of an African guy, in South London, wearing an American football jersey. It relates, in part, to the international connectedness of our sartorial choices and how they take on new meaning once removed from the context of their origins.

TJMWhat role do materials play in your process, and how has this transformed over the years?

TPThe choice of material and process is really important to my work. For my 'Numen' series (2016), which is a continuation of my investigation into Greek, Roman, and Egyptian mythology, I used lost-wax casting, a technique that dates back to ancient times. But the work is made of aluminium, a modern material once used in airplanes for intercontinental flights during the golden age of flight, and now it's used in MacBooks and Coke cans.

I'm really affected by process; it's intrinsic to what I do. The way I do something is very connected to how you're supposed to understand it, so for me not to talk about how something is made would be to ignore part of the work. I understand some people don't want to know about the making so much and that's fine. But I'm always trying to be honest with myself when I'm working, which means asking myself questions all the time and having to be really truthful with how I respond. It's easy to convince yourself that where you ended up is where you intended to be or the result that you have is what you intended to make but sometimes you have to go back and start again. It's this honesty and rigour that creates worthwhile work.

TJMCould you talk us through some of your current projects, including your forthcoming solo exhibition at The Power Plant Contemporary Art Gallery in Toronto?

TPWe're in the process of pouring a nine-foot bronze sculpture, Cover Up (The Reveal) (2019), just outside of Philadelphia. The Rennie Collection has purchased that work, along with a three-foot version of a previous piece, which they are loaning to my upcoming solo exhibition at The Power Plant Contemporary Art Gallery in Toronto.

The exhibition, Ordinary Men, is my first solo show in Canada and inside the gallery, I'm presenting three newly commissioned works alongside several smaller bronzes and photographs that challenge the erasure of Black bodies within the traditions of classical sculpture. Outside, in Canada Square, will be my 'Numen' series from 2016. To the west, on the South Terrace, Cover Up (The Reveal) (2019) will be presented. These four works extend the exhibition's reach further into public spaces to engage visitors both inside and outside the gallery, confronting them, and passers-by, with images of Black men on a monumental scale.

The figure in Cover Up (The Reveal) (2019) is wearing a hooded sweatshirt and when the piece is installed, outside, there will be a moment when people respond to it in light of the much-publicised state violence against Black people in the U.S. I started this piece in early 2017 and these deaths have persisted with shocking but unsurprising regularity.

TJMYou've also worked in performance, presenting your own body in action as opposed to the representations or mediations of imagined persons. You performed one of your most talked about pieces, Licked (2001), while you were still a student at Chelsea College of Arts.

TPI have loads of ideas for performances pieces; I think I'm a bit of a frustrated actor. Licked (2001) was supposed to be a performance resulting in an installation. At that stage I was so taken by the reception of the YBAs and the whole idea of spectacle that I wanted to see if I could create a furore, or some kind of rumour, potentially: I wanted word to travel that 'someone is licking the inside of this gallery'. Would people come and see it, I wondered? Would those entering the space after the performance believe it had taken place?

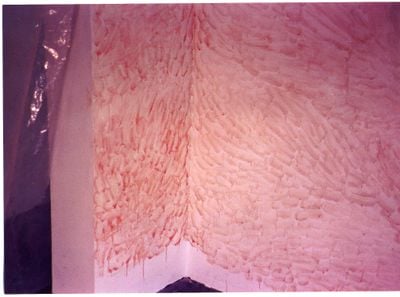

When I started licking the walls as part of the performance, I held my hands up like a frame, using them and the rest of my body to measure how far and where I'd gone. The moment I made contact with the wall, it sucked all the moisture off my tongue—so I got a bit panicked and had to re-think my strategy. I got a bowl, a flannel, a large bottle of water, and chewing gum. I chewed the gum to get my saliva going while lubricating the wall with the wet flannel and that seemed to work. Then I got about a metre in and I could see the walls getting dirtier and rougher. Not long after, I could taste iron in my mouth—it was my tongue bleeding. And I thought I could just wash it off since it was only a small amount at that stage but I must have covered another two feet or so before the marks I was making with my tongue started to look like they had been painted on with a brush dipped in red paint.

TJMSo the work changed in ways that you had not anticipated. How did you respond?

TPI realised it was a visual record of a process and a kind of portrait. People could watch me through a plastic sheet that was fixed across the entrance to the gallery and by that stage the work's power dynamic had shifted massively: instead of people seeing a room covered in my invisible saliva, they watched me make my way across a room, leaving bloodied marks as a visible record of my action. I got as far as I could go—going as high, as low, and as far into the corners as I could—and I did this for three days.

Then came the stage when people didn't believe that it was blood. It became a far more effective piece because of the bleeding. The piece was really well received and rumour travelled to different colleges. It was even featured in the BBC 4 documentary, Where Is Modern Art Now, presented by Gus Casely-Hayford. It was then that I had to make a decision about what I wanted to do and where I wanted my work to go. I was really into Matthew Barney's work at the time because of its physicality and I was dealing with masculinity—though I hadn't quite realised I was doing it. I already had ideas for my next performance piece and I felt I had to outdo Licked in terms of shock value. Part of the plan for the follow-up performance involved hanging myself upside down. But then I realised I didn't want to just be making 'shock art' and courting attention with this very theatrical, crowd-provoking work. That's when I thought: no more performance.

Since then I've made videos of me cleaning and lacing my trainers and my hand photographs are performative, but they are all in line with what I'm working on now—narrative work about the formation of histories. But Licked was a really pivotal piece and it took place so early on in my career. I often start talks about my practice with that piece; it's still so integral to what I'm trying to do now.

TJMLicked (2001) reminds me of acts of ritual sacrifice performed by religious devotees who crawl on their hands and knees to a sacred site, for example. I noticed a small portrait of the Virgin Mary on the wall in your studio, which got me thinking about religious icons and how they are part of a dominant aesthetic tradition for many members of the Black diaspora. You've spoken of your sculpture as approaching the stately aggrandisement of men of rank—are there any parts of it that relate to religious iconography?

TPYes, ideas around reverence and religious icons have informed my work. I think they started off as unconscious understandings, but they have become more of a conscious thing over time. In 2009, while on residency at the British School in Rome, I looked at the sculptures of saints in the city's churches. I was there for four months and I looked at almost every church and every sculpture. I was intrigued by the idea that, when these artists were creating religious artefacts, like votive statues, they sculpted them with great attention to detail—even the parts that aren't so visible, like the inside of a hand. This level of care functioned as part of the offering and a sign of reverence for the person represented.

The sculptures that were in the 2018 edition of Sculpture in the City were from the 'Numen' series, which is a word for a divine presence, and subtitled Shifting Votive One and Two, which relates to ideas of whom we choose to worship. The marble plinths that form part of the works act as a sign of reverence for the depicted heads that are placed upon them. I'm a big fan of plinths and the status they confer. I spent a year working on a 'super-plinth'—that started as a white painted plinth meticulously hand-sanded to a shimmering finish, but that changed to one formed of several stacked levels of glossy white Perspex. I'm not sure I'd do it again.

When I started sculpting heads, I saw a guy sitting in a car with his window down, visible from his neck up and I made this into a sculpture, Ackerman Road (2006), the base for which I finished with car spray paint. For vast swathes of the population, cars still very much function as a status symbol and so in that sense they relate to my interest in how power and prestige are conferred and finishing the base with car spray paint helped make the object contemporary without lapsing into tropes of using unusual materials or found objects as plinths, which I think is a bit tired.

TJMYou've also made work that plays with the relationship between abstraction and figuration.

TPAt Frieze London 2018, I debuted Power Object (Section 1, No. 1). It's a cross section of a large figurative sculpture—a section taken from the groin—but it looks abstract and I've used tool marks to create a texture on its curved surface, with its ends hand-polished to a mirror-like finish. It's then been placed onto a Carrara marble base. The work relates to Barbara Hepworth's and Henry Moore's tradition of large figurative sculpture—the kind you see at Tate Britain. So I'm setting myself right up against that history. The second part of the work's title, 'Section 1, No.1' refers to British stop and search policy, which allows police officers to exercise their power to search people at any time—a vastly disproportionate number of whom will be Black.

TJMMost of the sculptures you've made are of men, and the issues they deal with relate to the experience of Black men. But you've recently been working on a sculpture of a woman.

TPLay it Down (On The Edge Of Beauty) (2019) is the first sculpture of a woman's head that I've done. Previously I sculpted Black men because theirs is an experience I could relate to, as a Black man. When it came to women, I didn't want to go into it lightly and presume to know the workings of their minds—given that I was intent on capturing those truthful 'in-between' moments. And even after discussions with women about this over the years—particularly women of colour—who have told me, consistently and in no uncertain terms, that they want to be seen, to be represented, I still felt like I didn't necessarily know how to.

Now I realise there doesn't need to be a neat symmetry between the work I make of men and my work on women. This freed me to talk about the things I do understand. For one, how in popular culture, media, and fashion it's common to take aspects, or signifiers, of Black womanhood and use them while not acknowledging those from whom they are taken or, worse yet, castigating and demonising their originators—taking certain hairstyles and placing them on white models, pretending it's some innovation, while punishing young Black women for wearing the same hair.

This new sculpture, Lay It Down, looks at 'baby hairs'. It's slightly smaller than the heads in my 'Numen' series, which refer to Greek and Egyptian deities, but the idea of deifying is still present—so I cast it in bronze but without giving it a patina so I could have an overt sense of the material come through. The work has been well received so I'm looking forward to making more of them. I'm beginning to get together the reference material for the next works in the series right now, so there should be enough for a show in 2020, if not sooner.—[O]