Asia Society's First Triennial Dreams of Unity

Sun Xun, July Coming Soon (2019). Ink and colour on silk album. 24-page folding album. Open: 43.5 x 756 x .5 cm; closed: 43.5 x 31.5 x 5.5 cm. Courtesy the artist and ShanghART Gallery. Photo: Alex Wang (ShanghART Gallery).

Amid the many traumas that have seemingly flipped the world upside down over this past year, the Asia Society in New York unveiled its inaugural triennial on the eve of a historic presidential election in the United States.

Originally scheduled to debut in June, We Do Not Dream Alone (27 October 2020–27 June 2021) brings together works by 40 artists of Asian descent, including Kimsooja, Dinh Q. Lê, Anne Samat, Melati Suryodarmo, and Reza Aramesh.

The endeavour strives to amplify voices of a frequently stereotyped and often maligned demographic, as demonstrated time and again by seismic events like the so-called War on Terror and the current pandemic, which remains starkly underrepresented within both contemporary art and popular culture.

Ambitious in scope, the triennial, originally intended to take place across multiple venues across New York City, such as Governors Island and the Lincoln Center, has since been bisected into two parts due to the forced postponement of presentations resulting from Covid-19.

Within the current context of searing divisions in the United States and beyond, a decidedly political undertone charges the first segment of the triennial's primary exhibition at Asia Society's Park Avenue museum, which is fundamentally a cry for unity, healing, and compassion crafted by curators Boon Hui Tan and Michelle Yun.

A sense of commonality emerges as a recurring theme among works presented, drawing parallels between nationalities, religions, and social identities that are too often pitted against one another. Two identical sculptures by Xu Zhen® open the show: a collapsing of replicas of an 11th-century Cambodian male figure and the 2nd-century Roman Statue of Venus Genetrix, which is in the collection of the J. Paul Getty Museum (Eternity—Male Figure, Statue of Venus Genetrix, 2019–2020).

Among the highlights is a suite of largely monochromatic works on paper by the late Nandalal Bose, an iconic pioneer of Indian Modernism who synthesised classical Indian aesthetics with East Asian sumi-e techniques, a mode of painting with black ink wash that originated in China in the Song dynasty, and was brought to Japan in the 14th century by Buddhist monks. Vignettes of daily life drawn from memory portray pedestrian moments, such as a woman standing beneath a rising sun, and a caravan towed by oxen.

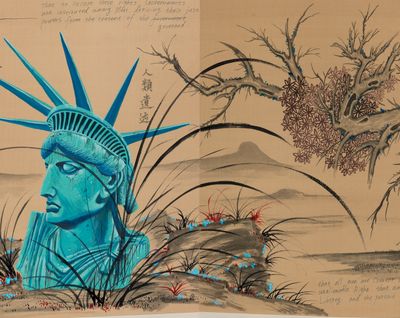

Although the artists on show live and work in far-flung corners of a massive geographic expanse, they demonstrate the vibrant exchange of ideas that globalism has brought onto the world. These points of interconnectedness are especially evident in Xu Bing and Sun Xun's new commissions, which respond to the historical and present ties between the United States and China.

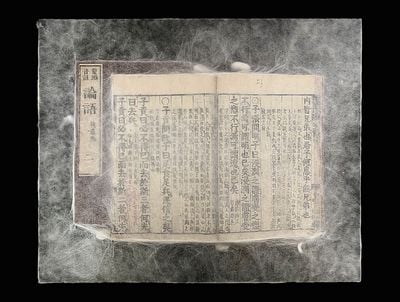

Xu's Silkworm Book: The Analects of Confucius (2019) takes a Confucian text known to have inspired America's founding fathers and encases it in delicate silk, while Sun's July Coming Soon (2019) pairs the artist's English ruminations with Song Dynasty-styled renderings to illustrate the threats that Donald Trump's policies pose to the world. Presented alongside these works is a 19th-century copy of the Declaration of Independence.

Other works respond to the trials and tribulations that the modern era has brought to Asia. Minouk Lim's multimedia installation, for instance, powerfully evokes the pain that deeply traumatised a generation of Koreans who lived through the dark days of a civil war propelled by international superpowers.

Three menacing, towering sculptures surround a video work titled It's a Name I Gave Myself (2018), which culls footage from a live broadcast organised by the KBS network in 1983, precisely three decades after the conclusion of the Korean War, wherein individuals separated and displaced by the war attempt to seek out lost relatives.

Lim's agonising work focuses on segments featuring subjects who were too young during the war to remember their own given names. Each holding a sign bearing a serialised number to identify speakers, they recount faint childhood memories in the hopes that a long-lost relative might recognise them and call the hotline number at the bottom of the television screen.

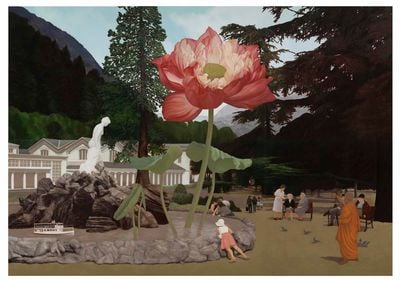

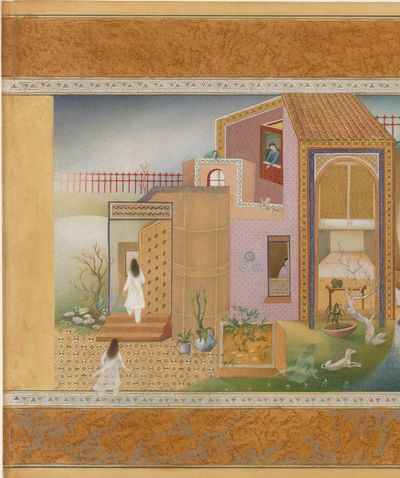

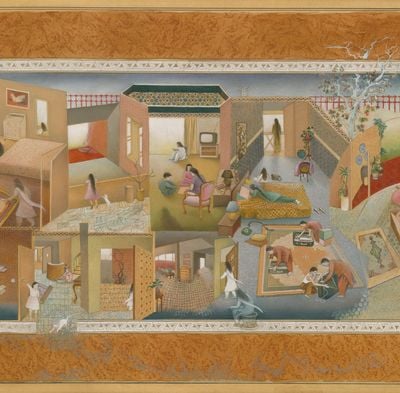

Elsewhere, a masterful, early painting by Shahzia Sikander chronicles a woman's coming-of-age in Pakistan during the 1980s.

Created for the artist's thesis project at the National College of Arts in Lahore, The Scroll (1989–1990) brings the centuries-old tradition of Indo-Persian miniature painting into dialogue with Sikander's own feminist inclinations. A recurring figure, cloaked in white with flowing black hair, weaves through a sprawling interior space, and forgoes conventionally female domestic chores performed by others in the scene, in favour of solitary intellectual pursuits like reading and writing.

But while Sikander's primary character does not engage in any of the activities taking place around her, the artist does not patronise domesticity; rather, the work demonstrates how such activity can harmoniously co-exist alongside more aspirational pursuits.

Across town, an auxiliary exhibition mounted at the New-York Historical Society, Dreaming Together (23 October 2020–25 July 2021), comprises more than 35 works pulled from both institutions' collections. Curated by Wendy N.E. Ikemoto, the presentation explores conceptual and visual similarities between works by Asian artists including teamLab and Huang Yan, and those by American and European counterparts such as Betye Saar and Pablo Picasso.

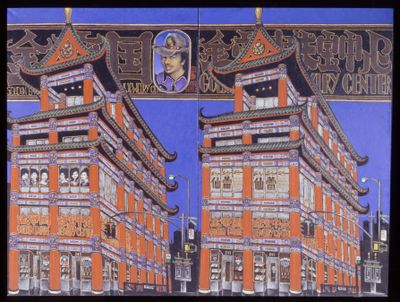

Although groupings of works felt arbitrary and overcrowded overall, Martin Wong's diptych Canal Street (1992) anchored this one-room show. Created seven years prior to his untimely death from AIDS, the ornately detailed paintings depict a building on the titular thoroughfare, wrapped in red columns and capped by a pagoda roof. This traditional-seeming façade houses businesses that typify America's exoticised Chinatowns: nondescript jewellery stores and massage parlours bearing dual language signs that call out to native and foreign passersby alike.

Wong's singular practice collided the artist's identity as a queer, Chinese-American man with New York City's grittiness and hybridity of cultures, and Canal Street registers as a candid love letter to a neighbourhood that bridges two worlds. A small self-portrait wherein Wong grins beneath his trademark mustache and cowboy hat, located along the top edges of the painting, radiates his admiration.

Taken as a whole, the triennial offers a refreshing reset on conventional understandings of modern and contemporary Asian art, where visibility has been far too restricted to a disproportionately small pool of artists whose works are peddled at countless art fairs and stateside retrospectives. While other institutions have previously attempted large-scale exhibitions dedicated to specific regions, the fact that it has taken so long to mount a pan-Asian tribute in an urban landscape where nearly one and a quarter million citizens claim to be of Asian descent, only further illustrates the initiative's importance.

It will be exciting to witness the next editions of Asia Society's new endeavour, presumably unhindered by a global public health crisis. Before then, the second part of Asia Society's first Triennial will open on 16 March 2021 with works by the likes of Ahmet Öğüt, Susie Ibarra, Wen Hui, and more.—[O]