Gavin Jantjes: What Freedom Means

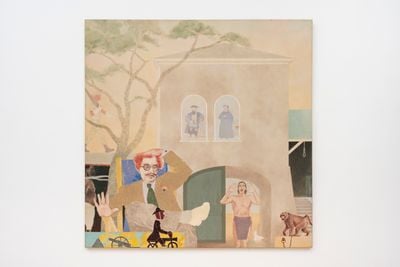

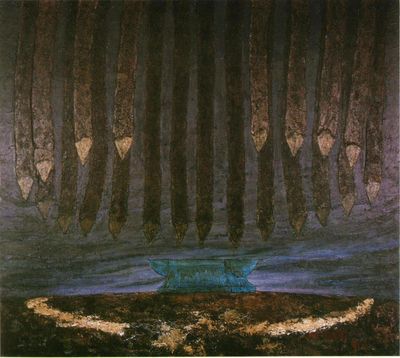

Gavin Jantjes, Untitled (1989). Acrylic on four canvases and ceramic egg. 300 x 304 x 56 cm. Courtesy the artist. © Gavin Jantjes, licensed by DACS. Photo: Ann Purkis.

Organised by Whitechapel Gallery and Sharjah Art Foundation with The Africa Institute, Gavin Jantjes: To Be Free! A Retrospective 1970–2023 celebrates the life of an artist who is many things—activist, printmaker, painter, writer, curator, and artistic director.

Curated by Salah M. Hassan in Sharjah with Gilane Tawadros and Cameron Foote for the Whitechapel iteration (12 June–1 September 2024), over 100 works reflect a practice shaped by personal and political transformation.

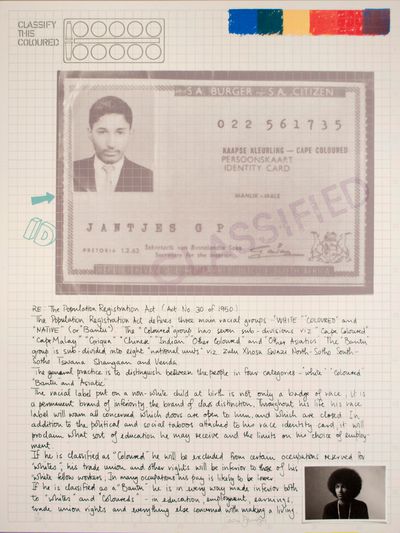

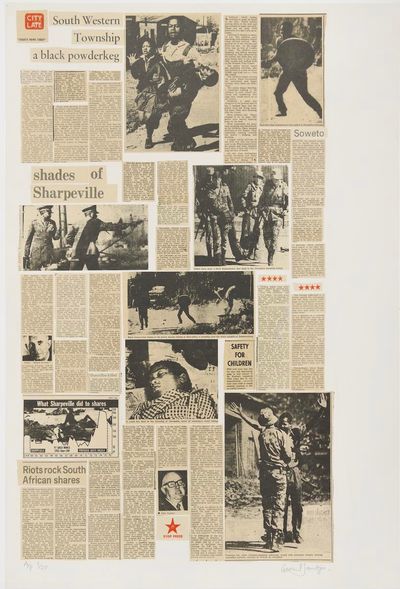

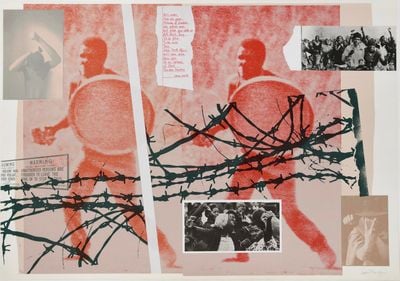

Among Jantjes' early works is A South African Colouring Book (1974–1975), conceived to support the Anti-Apartheid struggle and banned in South Africa in 1978. Eleven screenprints with collage confront life under Apartheid, with photographs and text drawn from the archives of the African National Congress, the International Defence and Aid Fund, UN, and UNESCO, as well as Ernest Cole's 1967 book House of Bondage and German magazine Stern.

Each page plays on the composition of a children's activity book. There's a colour-in portrait of former South African prime minister John Vorster—quoted on another page titled 'The True Colours of the State', claiming Black South Africans should have no political rights because their purpose is to serve whites—with one frame depicting him as Hitler.

One page invites readers to 'Classify this Coloured' based on the 1950 Population Registration Act's racial categories: 'white', 'coloured' [mixed race], and 'native' [Black]. Another page shows a 'WHITES ONLY' sign above text mentioning the growing case law around whiteness as a legal definition.

Apartheid's appalling, all-encompassing violence is highlighted on every sheet. Among images of the 1960 Sharpeville Massacre, when police indiscriminately killed people protesting the pass laws requiring non-whites to hold authorised documentation to move around the country, Jantjes invites readers to 'Colour these People Dead', which is effectively what South Africa's legal apparatus did.

As a result of the pass laws, the country's daily average prison population was among the world's highest at the time—a state-sanctioned method to control an occupied and dehumanised population that finds resonance in the current conditions of occupied Palestine.

Apartheid's appalling, all-encompassing violence is highlighted on every sheet.

Influenced by Bertolt Brecht's notion that art is an instrument of political struggle, A South African Colouring Book was in part the artist's response to his observations studying at Hamburg Art Academy, where he arrived in 1970 on a DAAD scholarship. (He was granted political asylum in Germany in 1973.)

Coming to Europe after the May 1968 student movement in France, he was struck by the lack of awareness protestors had of Apartheid amid the Anti-Vietnam War movement and the broader wave of Third World Liberation movements that arose in the postwar era. 'The issues of race and identity within national cultures as postulated by W.E.B. Du Bois and Frantz Fanon had not yet penetrated the almost impervious rhetoric of the Marxists, Marxist-Leninists, and Maoist student groups,' Jantjes wrote.1

Further, 'In West German popular consciousness, apartheid South Africa was a friend and business partner,' he found—an ally in the Cold War during which time the United States and Soviet Union wrought havoc fighting proxy neocolonial wars in a zero-sum drive for world power.

Given the dearth of coverage and contextualisation in European broadcast media, Jantjes found similarities between Europeans he encountered abroad and white South Africans at home: neither had entered the townships to see the brutality of Apartheid for themselves.

Jantjes' prints confronted that silence by taking advantage of new print technologies, the photograph as evidence, and the directness of Pop art to agitate against erasure.

The intimacy of the colouring book created a point of contact between both worlds. A page reading 'Colour this Slavery Golden' connects the history of colonialism and slavery, a golden age for its perpetrators and beneficiaries, and South Africa's roots in it. The same history joined both sides of the Black Atlantic in the struggle for independence from colonialism and its neocolonial forms in the 20th century.

Among Apartheid's architects was Jan Smuts, who helped write the UN Charter's preamble in 1945, including its mention of human rights. W.E.B. Du Bois called out that hypocrisy in a 1947 appeal to recognise the Black American plight, highlighting the international community's continued allegiance to white supremacy given South Africa's defence of humanity while enslaving its Black majority.2

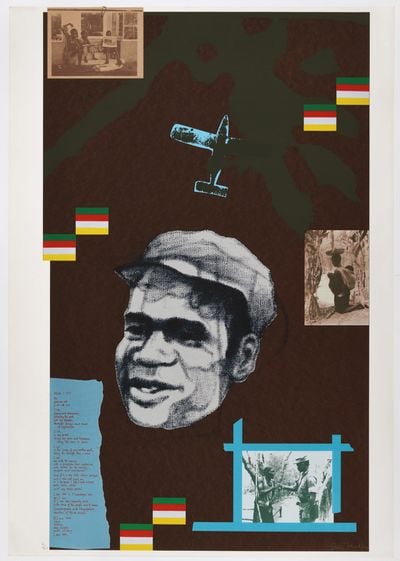

Jantjes, like those struggling for freedom in the empire's former colonies and metropoles at the time, knew that systemic violence intimately—as do those today. The screenprint and collage For Mozambique (1975), for instance, commemorates Eduardo Chivambo Mondlane, the founding president of FRELIMO, a movement that fought for independence from Portuguese rule in Mozambique and later governed the country.

Mondlane was assassinated in 1969, around the same time as several other African independence leaders by former colonisers and their allies. Among them was Patrice Lumumba, independent Congo's first prime minister, who was killed by 'Congolese politicians and Belgian "advisers" with the tacit support of the United States and the malign neglect of the United Nations', as Isaac Chotiner wrote for The New Yorker.

Jantjes' prints also immortalised figures like writer and activist Angela Davis, Ghana's first President Kwame Nkrumah, and Amilcar Cabral, who led the African Independence Party for Guinea and Cape Verde. Cabral's photo appears in the 1974 print It is Our Peoples, next to his quote locating 'the strength of justice, progress, and history' in the people.

Amplifying the histories of Third World solidarity to which the Anti-Apartheid struggle belonged is For Algeria (1978), which commemorates Algerian independence from French colonial rule in 1962 and its subsequent role as an international beacon of anti-imperialism. An image of Frantz Fanon is presented alongside his quote describing the coloniser as 'both organiser and victim of a system that has choked him to silence'.

Jantjes' prints confronted that silence by taking advantage of new print technologies, the photograph as evidence, and the directness of Pop art to agitate against erasure.

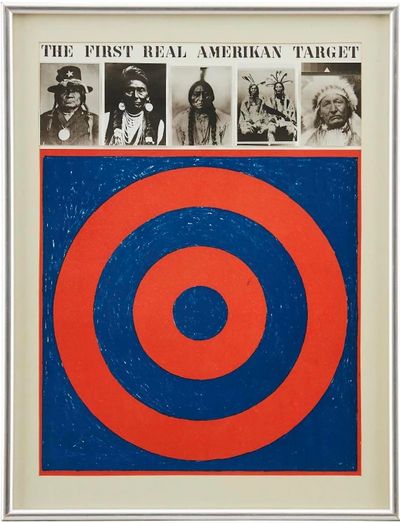

'Discourses around late modernist abstraction could, and very often, did deflect debate away from the issue of an artist's role in an undemocratic society,' Jantjes recalled in the context of South Africa, bringing to mind the CIA's use of postwar American abstract art as anti-Soviet propaganda. As if to respond, The First Real AmeriKan Target (1974) lines up images of Indigenous Americans above Jasper John's iconic target motif to critique the genocide on which the United States was built, and which it has yet to truly reckon with.

Jantjes' use of pop aesthetics to serve revolutionary struggle was highly effective. Not only did it communicate documentary facts and fragments to wider audiences but bypassed media blackouts and political obfuscations of lived experiences of oppression.

In 1976, A South African Colouring Book was included in an exhibition at London's ICA, the same year the Soweto Uprising saw Black students killed for protesting the introduction of Afrikaans at school. Then, in 1978, the International University Exchange Fund created an edition distributed by the UN Special Committee Against Apartheid. That year, Jantjes designed a series of posters for the UN's official Anti-Apartheid year, as the visual campaign director for the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.

In 1977, A South African Colouring Book was shown in documenta 6 at the request of Joseph Beuys, Jantjes' former professor, who told Jantjes he was not himself in his prints but 'reacting to something'. Jantjes says he didn't realise it at the time. Out of necessity, activism came first.

Hence the multi-faceted meaning of his survey title, To Be Free! As Salah M. Hassan writes, the idea of freedom in this survey symbolises 'the determination of many South African artists and writers to explore all forms of artistic and aesthetic expression with full freedom, unbound by the Eurocentric gaze and its prescribed roles and assumptions for Black artists'. (A determination shared by artists across the world dealing with the mainstream art world's Western centrism.)

In the late 1970s, Jantjes began applying his activist aesthetics to the use of colour, shade, and form on canvas, most notably by rubbing and scoring paint into print-like surfaces.

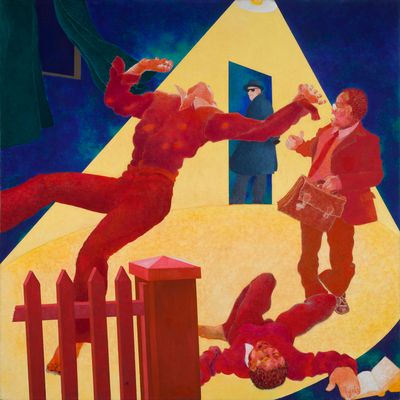

In Amaxesha Wesikolo ne Sintsuku (School Days and Nights) (1977), red-earth figures representing Soweto protestors tumble to the ground in a room where a white government official enters the shadows through a backdoor. In Quietly at Tea (1978), white men wearing markers of their supremacy—including a bowler hat and crucifix—circle a piano served by house staff. An African figurine sits upturned in the foreground.

Jantjes calls what followed 'picture poems'. The seven large canvases in the 'Korabra' series (1986), named after the Akan proverb 'to go and come back', explore Africa's history on a symbolic plane. In Vaal (1987), a circle of grey stones in a savannah signifying Africa's Indigenous population foregrounds white ox-wagons of European settlers in the distance.

Describing the heavens as a neutral space, 'accessible to every human being' since it remains undefined and unclaimed by any nation, the 'Zulu' series (c. 1984–1990) looked to the cosmos and ancestral spirits. In the 'Water Bearer' series (1986), delicate, fluid celestial bodies are rendered in Indian ink on brown paper, while the 'Firebrand Drawings' (1987) depict focal objects burned onto pages amid sequences of stars. In Firebrand Drawing 7, a stomach is bordered by a vertical line of stars on either side, like a poetic dedication made on a literati ink scroll or cave wall.

Throughout his evolution, Jantjes stayed connected to South Africa's political history. In the painting Half the Sky (1988), whose title refers to a Chinese proverb about women's labour, constellations are named after South African women activists including Miriam Makeba and Nadine Gordimer.

One year later, Jantjes made Untitled (1989), a large acrylic-on-canvas painting where a white umbilical cord shaped like an infinity loop connects a mask resembling those of the Fang people of Gabon and a figure from Picasso's Les Demoiselles D'Avignon (1907).

After moving to the United Kingdom—he set up a studio in Wiltshire in 1982—Jantjes turned to curatorial and teaching work to decentre Western-centric frames of reference in art. In 1986, he co-curated the Whitechapel Gallery exhibition From Two Worlds and became the first Black full-time senior lecturer in Fine Art at the Chelsea College of Arts.

The year prior, he completed The Dream, The Rumour and The Poet's Song, a public mural in Brixton, commissioned by the Greater London Council to tell the story of Britain's Afro-Caribbean community, which pulled no punches in criticising the racism they have endured.

Jantjes' work took him to Oslo, where he served as artistic director of Henie Onstad Art Center from 1998 to 2004, before joining Norway's National Museum as senior curator until 2014. The artist's return to painting following these institutional roles reveals a practice that has continued to develop.

'The Exogenic Series (Aqua)' (2017) came first, with swathes of marbling on canvas that create luminous pools of rippling colour, their pigments layered at varying weights and viscosities, signalling a total departure from figuration. This approach was applied to smaller canvases in the 'Witney' series (2019–ongoing), named after the village in Oxfordshire where Jantjes settled in 2018, while the 'Sharjah' series (2022) expanded these fluid planes at panoramic scale.

Looking back to his early prints, which immersed viewers in the realities of an ongoing political struggle, these later abstractions are captivating in their pictorial formalism. The waves on canvas structure a multidimensionality that reflects the artist's open-ended exploration of fluid forms, calling viewers into a space beyond definition. From then to now, there is a continuity in this invitation to be free. —[O]

1 Gavin Jantjes, 'A South African Colouring Book', Catalogue Note, 2018, Sotheby's.

2 W.E.B. Dubois, 'An Appeal To The World: A Statement of Denial of Human Rights to Minorities in the Case of citizens of Negro Descent in the United States of America and an Appeal to the United Nations for Redress', 1947.