Jennifer Packer: Seeing in Real Time

Exhibition view (detail): Jennifer Packer, The Eye Is Not Satisfied With Seeing, Serpentine Galleries, London (19 May—22 August 2021). Courtesy Serpentine Galleries. Photo: George Darrell.

Jennifer Packer's first solo exhibition in a European institution, The Eye Is Not Satisfied With Seeing (19 May—22 August 2021), presents new and recent works across six spaces in the Serpentine Gallery's Grade II-listed former tea pavilion in London.

Rather than arrange the show in a manner that separates striking portraits, rarely seen drawings, and unique interpretations of vanitas flowers, the overall hang demonstrates the synergy between these subjects. The move undoubtedly echoes Packer's desire, as she has stated previously, for drawing to take its rightful place next to painting, rather than serve as a precursor to a finished work or sketch to an unfinished idea.

Across the show, drawings created from memory demonstrate Packer's engagement with the genre as 'a counter-practice'—a way of 'argu[ing] with a painting.'1

Rendered in black charcoal, which produces a range of greys, and pink, purple, blue, and white pastels, The Mind Is Its Own Place (2020) revolves around two figures leaning into each other side by side as one gazes down at the other who is asleep.

Though abstracted, the rendering of these bodies highlights a sense of intimacy and care. In her exhibition essay for the exhibition's catalogue, scholar Christina Sharpe connects the raised knee in the drawing to the late George Floyd and American football player Colin Kaepernick's protest stance. What is really going on, however, is left for the viewer to interpret, as is signatory in Packer's work.

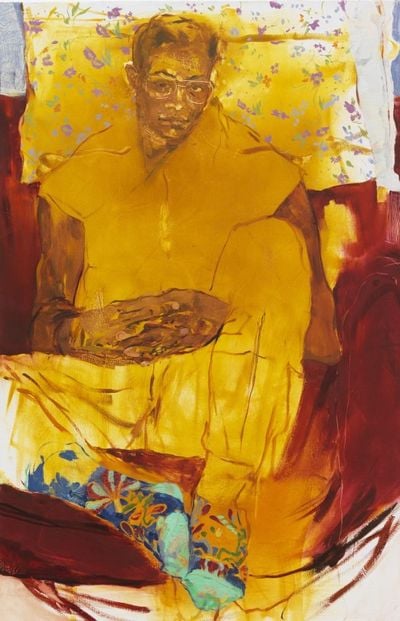

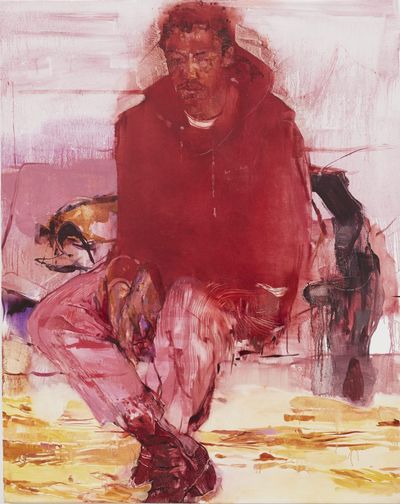

Curated by Melissa Blanchflower with Natalia Grabowska, the exhibition begins in the South Gallery where differently sized canvases are arranged as a constellation of Packer's subjects. These range from the small portrait Token (2020), depicting a crimson headshot of a sleeping man, to the medium-sized still-life painting of a commemorative flower bouquet, Untitled (2016), to larger works like the vivid yellow-hued portrait of Tia (2017) lounging but gazing nonchalantly.

Every painting demonstrates Packer's skillful use of loose lines, brush strokes, and limited colour palette to create dynamic and complex reflections of contemporary Black lives based on real experiences.

Transfigurations (He's No Saint) (2017) shows a topless man lying on his back with arms raised above his head and hands clasped against his forehead. The figure is composed of loose brushstrokes and lines built up from contrasting shades of burnt oranges and reds with a distinct bright yellow midriff. Green and red shorts suggest that perhaps this person is sunbathing or relaxing post-swim, as he gazes at the viewer with half-closed eyes.

Yet, another reading of this same painting could transport the figure to a scenario where he is being stopped and searched, arms raised in surrender at yet another interrogation. In this scenario, his gaze becomes weary; like that of a marked man.

'We belong here. We deserve to be seen and acknowledged in real time. We deserve to be heard and to be imaged with shameless generosity and accuracy.'

That double entendre—of scenarios whose meanings open up possibilities of interpretation—extends to Packer's style overall. Rather than centre on the 20th-century Western art historical tradition that tends to pit abstraction and figuration against each other based on their tensions, Packer attends to their representational qualities, with brushwork that allows forms to at once dissolve into and emerge from the surface.

Packer's backgrounds—most often interior spaces—are as ambiguous as the figures occupying the frame. April, Restless (2017) captures this sense of liminality. A female figure sits on a chair surrounded by a yellow cloud-like haze, making it hard to separate body from the seat. Interior details such as a mint green table, typewriter, flowers, and personal memorabilia frame her, ever so subtly merging the figure and the surrounding interior as interconnected parts of a personal narrative.

Packer's love for her subjects is clear in every stroke, as well are the political acts embedded in their representation. These are real people from Packer's circle—family, lovers, friends, artists, peers; among them, fellow Yale graduates and teachers, including Eric N. Mack, Tomashi Jackson, Jordan Casteel, Tschabalala Self, and Devan Shimoyama.

'My inclination to paint, especially from life, is a completely political one', she has said. 'We belong here. We deserve to be seen and acknowledged in real time. We deserve to be heard and to be imaged with shameless generosity and accuracy.'2

In the Serpentine show, Packer's political insistence is perhaps most clearly expressed in Blessed Are Those Who Mourn (Breonna! Breonna!) (2020). This large painting depicts a home interior with yellow dripping down walls to indicate a sweltering summer's day as a Black man in sky-blue shorts reclines on a yellow sofa fast asleep, cooled by a fan in the background.

The work's title references the horrific and still unaccounted for murder of then 26-year-old Black medical worker Breonna Taylor, who was woken up and shot by police executing a search warrant as they broke into her Louisville apartment unannounced, drawing attention to the ongoing state-sanctioned violence directed at Black lives and a chilling reminder that not even home is safe.

Works by Packer commemorating Black lives are in line with Christina Sharpe's 'wake work'. Sharpe's ongoing inquiry involves 'plotting, mapping, and collecting the archives of the everyday of Black immanent and imminent death, and tracking the ways we resist, rupture, and disrupt that immanence and imminence aesthetically and materially.'3

Packer's floral still lifes, which she began painting from observation in 2012, add a deeply moving layer to this invitation to presence. According to the artist, some of her flower compositions serve as funerary bouquets and vessels of personal grief made in response to tragedies of state and institutional violence against Black Americans. But rather than repeat the viral spectacle of Black death, bodies are replaced metaphorically with bouquets symbolising the cyclicality and transience of life.

Say Her Name (2017) poignantly remembers African American political activist Sandra Bland who died while in police custody, widely believed to have been murdered, through a wilting bouquet of roses, carnations, lilies, and blue flowers, which could be cornflowers, irises, or delphiniums, spreading from the centre to the edge against a rich gold and black background.

In focusing on Black lives, Packer continues a redress in Western art history and the dearth of Black representation in portraiture. Notably, Kerry James Marshall, who for over 40 years continues to depict the daily lives of Black Americans in portraits, landscapes, domestic interiors, and amid historical events.

Other critically recognised Black female artists whose works upend portraiture traditions include Jordan Casteel, Njideka Akunyili Crosby, and Tschabalala Self, who all paint from life, and Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, whom Packer has cited as an influence in her work, who by contrast creates figures drawn from her imagination.4

Where Packer locates imagination in her work is expressed in the title of her Serpentine exhibition, which references Ecclesiastes 1:8, a bible verse alluding to a relentless quest for desires that are never satisfied through looking and seeing alone. Here, visual representation is posited as a form of bearing witness to the present.

In Ways of Seeing, John Berger situates the importance of representation in the moment when he states that 'no other kind of relic or text from the past can offer such direct testimony about the world which surrounded other people at other times.'5 Packer's painterly generosity calls us to see, now. —[O]

1. Youssra Manlaykhaf & Róisín McVeigh, 'Jennifer Packer's Political Still Lifes & Intimate Portraits Centre Black Lives,' Serpentine Galleries, https://www.serpentinegalleries.org/art-and-ideas/get-to-know-jennifer-packer/

2. Jennifer Packer: The Eye Is Not Satisfied With Seeing, press release, Serpentine Galleries, https://serpentine-uploads.s3.amazonaws.com/uploads/2020/11/PRESS-PACK-Jennifer-Packer-Serpentine-Dec-2020.pdf.

3. Christina Sharpe, 'The Wake,' In the Wake: On Blackness and Being, (Duke University Press: 2016), p.13.

4. Packer has previously spoken of being influenced by artists including Manet, Goya, Fantin-Latour, Botticelli, Matisse, Morandi, alongside contemporaries like Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, Kehinde Wiley, Hurvin Anderson, Nicole Eisenman who she describes as part of her 'painting family.' See Emily LaBarge, 'Jennifer Packer', 4 Columns, 29 January 2021, https://www.4columns.org/labarge-emily/jennifer-packer

5. John Berger, Ways of Seeing, Chapter 1, available at https://www.ways-of-seeing.com/ch1