Lynette Yiadom-Boakye's Resistant Figuration

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, Tie The Temptress To The Trojan (2016). Collection of Michael Bertrand, Toronto. © Courtesy Lynette Yiadom-Boakye.

Since her beginnings in the early 2000s as a student at London's prestigious Royal Academy Schools, Lynette Yiadom-Boakye has created mesmerising figurative paintings, etchings, and drawings that resist and complicate the assumed definition of portraiture.

Some 80 such works have come together for the artist's first major survey at Tate Britain, titled Fly In League With The Night (2 December 2020–9 May 2021). The show spans almost two decades, from the early 2000s to the present, yet resists a chronological display. Rather, curators Andrea Schlieker, Isabella Maidment, and Aïcha Mehrez have opted to explore correlations between bodies of work in relation to the artist's obsessive inquiry into the conditions of painting itself.

In Yiadom-Boakye's paintings, which combine muted palettes with bright hues such as yellow, blue, red, and green, figures are rendered in thick and oily strokes that become more refined with time.

In First (2003), one of the earliest works in the exhibition, the portrayal of a smirking figure errs on the side of abstraction, bar for the striking red robe that contrasts with a blood-red background, while Tie The Temptress To The Trojan (2016) shows a more sharply rendered man languishing across a bed draped in checkered sheets, indifferently returning the painter's gaze as if suddenly interrupted from his thoughts.

When confronted with such images, the mind tries to make meaning from each subtle gesture. Who is this person, and what has just happened? Whatever the scenario, what the painter foregrounds are bodies that communicate gesturally and outside of spoken language.

As a student at Falmouth School of Art on the Cornish coast, Yiadom-Boakye initially painted from life, but soon abandoned this for a fictive approach that treats figures as '... composites, ciphers, riddles.'1

Born and raised in South London, where she still lives and works, Western European painters—Impressionists including Édouard Manet and Paul Cézanne, and English portraitists like John Singer Sargent and Walter Sickert—offer clues to understanding the artist's formal concerns and aesthetics.

In Solitaire (2015), a young man dressed in black with a mink around his neck poses elegantly, while in Nightingale (2009) and A Passion Like No Other (2012), the inclusion of a ruff, a highly luxurious garment tracing back to the Renaissance period, hints at status.

Such compositions echo historic European portraiture, when focus shifted from religious idols to secular subjects. But while Yiadom-Boakye 'troubles the cliches and assumptions of the history of portraiture from within', to quote curator Isabella Maidment, she also resists the tendency to focus on identity—whether of her figures or her own as a British-Ghanaian artist.2

'At some point, I decided to strip away everything—all the narrative, all the background—and just have the figure with nothing else to interfere', she once explained; 'there was a very particular decision to take away everything.'3

Across Yiadom-Boakye's work, resistance and rebellion are central—an approach to painting that resonates profoundly at a time when the Western art historical canon is being necessarily upended, revised, and challenged.

When confronted with such images, the mind tries to make meaning from each subtle gesture. Who is this person, and what has just happened?

More interested in the conditions of painting and the alchemical effects of pigments and brushstrokes dancing with light on a canvas's surface than indulging the expectation that a diaspora artist must be self-referential or autobiographical, Yiadom-Boakye cites automatic drawing as an approach she adopts in creating paintings. Automatic drawing relates to the physiological term automatism, which describes bodily movements attributed to the unconscious.

In this sense, figuration seems a more apt frame to consider Yiadom-Boakye's work. Rather than depicting real sitters, fictitious Black figures are drawn from the artist's imagination and found imagery, freeing their bodies from the bounds of a specific time, place, or context.

These are individuals that represent Black life, but they are not fixed to a particular historicisation. Recurring motifs—gestures, landscapes, clothing, and poses—and the use of fiction as a critical tool frames the Black figure with a futurity that is yet to be defined.

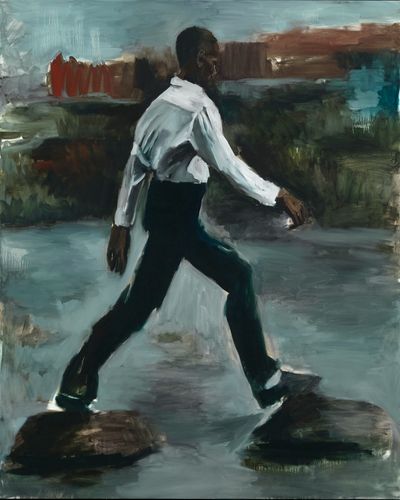

Also a prolific writer, the ambiguous titling of the artist's works, where word and images are unrelated yet serve to counter the limitations of the other, extend the challenge to gaze without framing. A Bounty Left Unpaid (2010), for example, shows a male figure dressed in a crisp white shirt and black trousers stepping across two rocks in the water. The title reveals nothing about this action, leaving it up to the viewer to associate word with image.

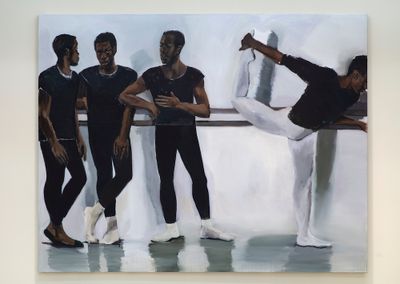

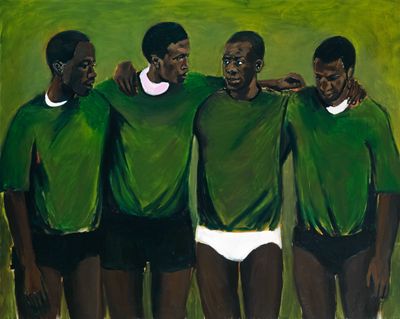

As Schlieker notes, groups of two, three, or more began to emerge in the artist's work around 2009, with poses and settings becoming more varied in later years and subjects engaged in shared activities like smoking, relaxing, or dancing.4

Throughout, colour blocking imbibes figurative studies on canvas with a certain geometry. A Concentration (2018), for example, shows four men dressed in black and white at a ballet rehearsal in a white studio; while in Complication (2013), four men in green jumpers and underwear—three in black, one in white—stand closely together, interlinked by one arm resting on the other's shoulder.

Architecture, light, and bodily engagement play an important part not only within the compositions that frame the artist's figures, but in the experience of the artist's paintings in exhibition spaces. Groups of paintings are often hung low on the artist's instruction, quietly commanding in their presence, with gallery walls treated like expanded frames.

In the David Adjaye-designed Ghana Pavilion at the 58th Venice Biennale in 2019, for instance, nine paintings from the 'Just Amongst Ourselves' series (2019) were hung on ochre walls made from soil imported from Ghana, mirroring the rich shades framing the subjects in each canvas, such as Blue Ink for An Infidel (2019), which portrays a man dressed in a white T-shirt and grey trousers posing elegantly as he emerges from a dark arched doorway.

Meanwhile, in Under-Song for a Cipher at the New Museum (3 May–3 September 2017), figures were captured in 17 paintings made between 2016 and 2017, including Crystals On The Mount (2016), which shows the profile of a smiling woman, whose burnt-orange T-shirt complimented the deep-red walls of the galleries.

At Tate Britain, however, walls have been painted eggshell white—a departure from the colour-filled spaces of recent exhibitions. This neutral backdrop perhaps serves as an embodiment of the studio or the space of the canvas itself, and by association representation and the artist's challenge of it.

In the exhibition catalogue, Isabella Maidment writes about a young man dressed in white standing against a white background suggestive of a studio wall in For The Sake Of Angels (2018). 'Other than the shadow of his profile there is nothing to place this man either in space, or in time—at least nowhere specific in the past century.'5

1 Lynette Yiadom-Boakye: Fly In League With The Night (18 November 2020–9 May 2021), Tate Britain, exhibition guide, https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-britain/exhibition/lynette-yiadom-boakye/exhibition-guide

2 Isabella Maidment, 'The Power of Invention', in Lynette Yiadom-Boakye: Fly In League With The Night, exhibition catalogue edited by Maidment, Isabella and Schlieker, Andreaeds (Tate Publishing, 2020), p.50.

3 Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, with contributions by Naomi Beckwith, Donatien Grau, Jennifer Higgie and Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, (New York: Prestel, 2014), p106.

4 Andrea Schlieker, 'The Paintings of Lynette Yiadom-Boakye' in Lynette Yiadom-Boakye: Fly In League With The Night, exhibition catalogue edited by Maidment, Isabella and Schlieker, Andreaeds (Tate Publishing, 2020), p.16.

5 Isabella Maidment, 'The Power of Invention', in Lynette Yiadom-Boakye: Fly In League With The Night, exhibition catalogue edited by Maidment, Isabella and Schlieker, Andreaeds (Tate Publishing, 2020), p. 49.