Liverpool Biennial Takes a Step Towards Reparations

Albert Ibokwe Khoza, The Black Circus of the Republic of Bantu (2023). Performance view: 12th Liverpool Biennial, uMoya: The Sacred Return of Lost Things, Tobacco Warehouse (10 June–17 September 2023). Courtesy Liverpool Biennial. Photo: Mark McNulty.

Liverpool's history as a city built off the slave trade is not easily forgotten. Once accounting for nearly half of Europe's involvement, its docksides have since rebranded with museums and attractions, where this year's Liverpool Biennial was introduced with healing in mind.

Necessarily perhaps. The biennial faced controversy after former director Fatoş Üstek resigned during the installation of its 11th edition, citing inadequate support from the biennial board, alongside two board members protesting the conditions that made her work 'untenable'. Its 10th edition was also met with criticisms of unpaid labour and disregard for artists, staff, and volunteers.

Seeking answers in Indigenous forms of knowledge, biennial director Sam Lackey invited Cape Town-based curator Khanyisile Mbongwa to organise its 12th edition, uMoya: The Sacred Return of Lost Things (10 June–17 September 2023).

uMoya, Zulu for spirit, breath, air, climate, and wind, was devised after Mbongwa was hit by a strong breeze while walking along Liverpool's docks—a choice that reflects the curator's commitment to engage the city and its locality.

Central to uMoya is the question of how to restore 'ancestral and Indigenous forms of knowledge, wisdom, and healing' lost to institutions in the Western world now tasked to 'care', and how to retain agency in the face of growing systemic inequalities and environmental decay. Or as Mbongwa calls it, how to be 'truly Alive' despite colonial 'Catastrophes'.

Contending with this task are performances and artworks by 35 artists and collectives—including Julien Creuzet, Albert Ibokwe Khoza, and Gala Porras-Kim—spread across eight venues, with additional outdoor locations.

A strong scent of soil emerges from a disused brick warehouse by Stanley Dock, a 20-minute walk from the city centre, which once stored tobacco imported from West Africa and the Caribbean, earning Liverpool its title as the British empire's second city.

At Tobacco Warehouse, Binta Diaw's Chorus of Soil (2023) draws attention to the trading in cotton, sugar, and later slaves that Liverpool's ports enabled, resulting in the forced displacement of over 1.5 million people, many of whom did not survive the crossing.

Using soil plots and seeds, the artist created a near-to-scale replica of Liverpool's 18th-century Brooks slave ship, named after the family who built Liverpool's town hall and still has a street named after them.

Modelled after a 1788 drawing commissioned by abolitionists showing sections of the vessel crammed with bodies, the materials composing Diaw's original model creates links to an expanded and historical network of exploitation. Seeds of okra and black-eyed peas allude to plantations, but Diaw reclaims the labour of working the soil as an emancipatory gesture, offering a view towards generative growth.

The question of how then to sit with these histories of exploitation in Liverpool and beyond is explored at FACT Liverpool, with Belinda Kazeem-Kamiński's six-channel video installation Respire (Liverpool) (2023) suggesting that the answer is together.

Filmed with adults and children from Liverpool's Black community, participants are shown each blowing into a red balloon that expands and contracts with every breath; their faces—tired, worried, and frightened—are presented in rotation across three large screens.

Draped fabrics—red, green, and black—appear on three smaller screens in between, which light up at intervals, appearing to guide the tempo of their breath. Still, the cavernous sound weighs down the room, amplified by a humming track by Bassano Bonelli Bassano urging to 'keep on'.

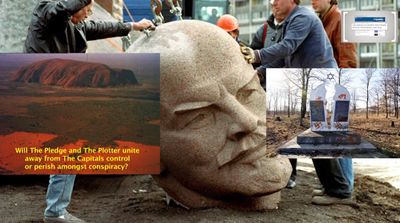

That call to 'keep on' becomes a rallying cry at the World Museum, where Brook Andrew's SMASH IT (2018) is nestled between Benin artefacts in the World Cultures gallery, currently undergoing a redevelopment plan seeking to introduce new perspectives to its African collection, which includes more than 10,000 items.

Andrew's 28-minute film questions the present-day relevance of colonial archives with a blend of interviews with Australia's Indigenous thinkers, archival films from the Smithsonian Institute, recent footage of protestors toppling statues, and excerpts from old ethnographic films.

Mirroring anarchy, SMASH IT unfolds many scenarios across different quadrants in a single frame, along with inverted colours, flickering text, and subtitles in both English and French. The eye is uncertain where to rest. Slight exhaustion kicks in eventually, which seems to amplify the call to act against historical injustices shaping institutions across society.

The exhaustion Andrew induces, then, reflects the challenges that come with dismantling centuries of systemic imbalances—as when contemporary art institutions, when pressured to change, express a willingness to make amends as if that were a quick fix.

Between entrenched histories and looming futures, uMoya seems to suggest that healing is a process, not a resolution.

With that in mind, Torkwase Dyson's Liquid a Place (2021), which opens the exhibition on the ground floor of Tate Liverpool, is a reminder that this was once the site of Britain's first commercial wet dock made to service the transatlantic slave trade. Three monumental steel anchors with semi-mirrored surfaces pay homage to lives lost at sea.

Dyson's sculptures foreshadow works by ten artists on the fourth floor, shown in a succession of rooms, where most are given their own space to breathe. Spread on the ground in one gallery is Edgar Calel's offering to his Mayan Kaqchikel ancestors, Ru k'ox k'ob'el jun ojer etemab'el (The Echo of an Ancient Form of Knowledge) (2021).

Tropical fruits and vegetables rest on stones of varying sizes, nodding to rituals from Calel's childhood in Guatemala where dreams shared over breakfast offer premonitions for the day. A rhubarb and avocado stand out among apples, bananas, and grapes; a white bouquet leans against a central rock, memorialising time's passage.

Calel's work and its six other versions are a reminder of how language can sometimes stand in for action. Acquired by the Tate at Frieze London in 2021 under a 13-year custodianship, Calel's installation is ascribed a sacredness that appears to evade the dynamics of property and ownership, thus underlying the inequalities protested by art institutions like Tate while simultaneously upholding them.

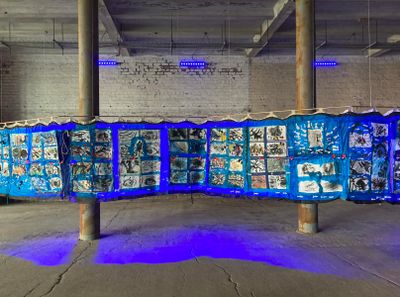

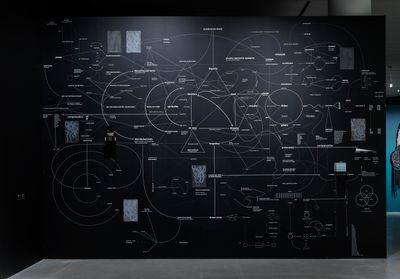

Nolan Oswald Dennis' No conciliation is possible (working diagram) (2018–ongoing) in the next room shows the equation is more complicated. The installation covers two entire walls with black wallpaper with elaborate mappings, overlapping diagrams, and inscriptions, positing what the artist calls a 'Black consciousness of space' while reflecting on the underlying causes of colonial violence.

Along the walls, cowry shells, pink crystals, and decolonial literature expand on the artist's reflections, while two piles of black bean bags on the ground invite seated contemplation.

Assembled inside an emerald gallery are Guadalupe Maravilla's towering 'Disease Throwers' (2019) made from objects such as loofahs, metal gongs, and plastic anatomical models, which narrate the artist's undocumented migration to the United States and later cancer diagnosis. Activated during healing ceremonies through sound, they recall uMoya's call to heal together.

Perhaps this is what curator Mbongwa meant by coming 'Alive'—when art is not only a way to reclaim individual agency but makes space for others to do the same.

What follows in the next rooms are quieter but equally poignant works such as Lubaina Himid's acrylic on canvas, Between the Two my Heart is Balanced (1991). Two Black women in African dress stand on a grey boat at sea, tearing through a stack of maps between them.

In the next room, Shannon Alonzo's Washerwoman (2018) comprises a bust-less female figure made of beeswax and resin seated at one end of a metal wash bucket. The form is remarkable for the contrasting textures between the shredded fabric of the figure's clothing, including an expansive skirt made of wooden cloth pins, and the visceral surface of her skin.

A closer look reveals hands soiled by manual labour gripping onto laundry that can never fully be cleansed, recalling the embedded nature of historic events, of which devastation can never be fully repaired.

At the Cotton Exchange, a live painting by Alonzo hints at how art-making can help us process these events through active re-imagination and engagement. Drawn and erased throughout the biennial's duration, a mural of Caribbean faces and bodies tangled in mangrove roots celebrates Trinidad's carnival culture and its history as a place of refuge.

Alonzo's painting connects to Mbongwa's call through this biennial to come 'Alive', by using art to reclaim individual agency while making space for others to do the same. At Bluecoat, Benoît Piéron's play space for children attests to this hypothesis.

In a pink-walled attic, silk fabric forms a tent structure above a metal-framed bed ornamented with lively paper and light garlands, and a breakfast station, as part of Le Lit (2023). Surrounding the bed as part of Peluche Psychopompe VIII (2022) are two bat-shaped patchwork dolls made from repurposed hospital sheets, each hanging from an IV drip grounded in a potted plant beside a growth lamp. A third doll overlooks a reading corner, suspended above a foam alphabet mat that spells out 'love' and 'play'.

Having spent much of his childhood in hospitals for leukaemia treatment, Piéron's installation re-imagines illness as a 'potentiality' and encourages children to play regardless—an invitation that circles back to uMoya, and the parallels between present-day ills and what we make of them. Between entrenched histories and looming futures, healing is a process, not a resolution. —[O]