On Film: The Sydney Biennale Report Part Iii

Tacita Dean’s commission for the 19th Biennale of Sydney and Carriageworks, Event for a Stage, sits at the apex of a Biennale whose greatest successes have been in its film, video and performance works. Dean is an artist who courts chance and she described this, her first live work, as being based on a “series of profound misunderstandings” between herself, an actor and an unfamiliar medium. The work elegantly combines the traditions of theatre and radio with the rigors and science of filmmaking to make a contemporary portrait of three arts that are gradually losing time.

Two screen works in particular from the Biennale, one shot on film and the other whose subject is the theatre, are worth mentioning in their own right, but also because they serve as a primary introduction to Dean’s complex work, for a readership that will never see its original one-off iteration. Ann-Sofi Sidén and composer Jonathan Bepler’s Curtain Callers (2011) appears as a tracking shot through a theatre that reveals the action in the front of house, backstage and audience areas: an actor does a vocal warm up in the green room, prop makers paint a ventriloquist’s dummy and an usher stares blankly into space from the box office. The film, actually a series of expertly cut scenes filmed over one year at Stockholm’s Royal Dramatic Theatre, calls attention to the illusion of theater through the art of digital production and editing. Mathias Poledna’s short film A Village by the Sea (2011), shot on 35mm and using a 30-piece orchestra, expertly re-creates the mood and stylized look of a Golden age Hollywood musical. Both these works are homages to the superior quality of the threatened and de-popularised art forms they imitate and depict, while the latter work is, like Dean’s Event, at once anachronistic and contemporary.

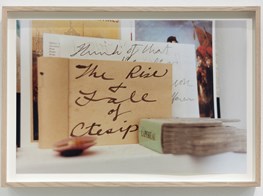

For her Biennale commission Dean was offered a stage in a theatre and four nights. It may seem an unusual commission for an artist distinguished by her work in film and her dedication to its preservation, however her work has long shown a preoccupation with not just the medium but also with the mechanics of performance and performers themselves. Dean’s first critical success as an artist came with The Blackboard drawings (1996), sublime large scale chalk drawings that are impossible to fix and are therefore always in shifting motion. In Kodak (2006) Dean used black and white Kodak 16mm to film the last Kodak factory in Europe to produce the very same stock; Foley Artist (1996) portrayed the art of creating sound for film and again used the medium to refer to itself. Event for a Stage follows a similar reflective logic to explore the nature of making film, theatre and radio. Dean isn’t opposed to digital processes; rather she believes they can exist in harmony with those of celluloid film. It was perhaps this harmony she was thinking of when she decided that Event for a Stage would have three manifestations: firstly four nights of live one-off performance that were shown as part of the Sydney Biennale in May, secondly as an ABC radio event in June and finally as an edited 16mm film.

Though Dean imposes one medium upon the other in Event for a Stage, each seems to maintain its own center of gravity. In the world of the theatre I would describe the action onstage as beginning with a man amidst a storm. But because this isn’t theatre or film, and by Dean’s own admission ‘not art’, the action is best described as beginning with the house lights on as a small crew busily set up two 16mm film cameras. The cameras roll, the clapperboards sound and then The Actor (Steven Dillane in pale stage make-up) performs a brief monologue as Prospero in Shakespeare’s The Tempest. To begin Event for a Stage with a reference to a play that is explicitly concerned with its own nature as a play, is a fitting start for an artwork that intends to do the same.

Event for a Stage is a work in progress, depicting as it does the processes inherent in making a script, a film and a work of live performance. One effect of all this artful self-consciousness is that everything, from the audience in their seats to the sound of technicians cleaning dust from the camera, is part of the narrative of process. Theatre is a battle of interpretation between playwright, script, actor and audience. Filmmaking is a more rigid process, where all involved are beholden to the temporal length of the reel. To accurately represent the theatre and filmmaking Dean must include the audience and crew as well. Eschewing the showy tactic of dramatizing their respective roles, she has simply mic’d all present for sound so that audience and crew in the initial Event for a Stage will become the soundtrack to the radio event and the performers in its final iteration as a 16mm film.

There is something particularly English about Event for a Stage, perhaps one affect of it being made for radio. But its Englishness is also there in the way the actor narrates his own circumstances and endures those circumstances despite his reservations, similar to the use of subjective camera and voice-over in the films of Patrick Keiller. Onstage Dillane fights between being an actual actor and playing one in an performance he feels is amorphic, difficult and ‘not theatre’. During the 40 minute event, Dillane acts out a simple and effective choreography to distinguish between the roles he plays: a white circle has been drawn between the raked seats, when he is inside the circle he is The Actor, reticently reading from scripts which he snatches from Dean who sits front row. The Actor occasionally reads from Heinrich von Kleist’s “On the Marionette Theatre”, a text that leads us to ask whose consciousness affects the action onstage and how the director performs their role.

I asked him whether he thought the man working the marionettes must be a dancer himself or at least have some notion of what constitutes beauty in dancing. He replied that though an activity might in its mechanics be a simple one it did not follow that it could be wholly conducted without feeling.

Outside of the circle it is Dillane himself who speaks. He gives short, vivid personal monologues that add gravitas to the stagecraft and are compelling to listen to. He speaks about his parent’s gradual slide into dementia, how his mother is happy in hers and how his father, before he died, developed an “unconventional relationship with characters from a television sitcom”. His father was Australian and he recalls a photograph of him standing under a jacaranda in the grounds of Sydney University. Dean often says she works closely with chance and coincidence, but there is a craft to knowing who and what to pick. Event for a Stage is perhaps the most artful, intelligent and, at 40 minutes, graceful portrait of an actor, a filmmaker and their respective crafts yet made. -[O]

Stella Rosa McDonald has a Master of Fine Arts from the University of New South Wales (COFA) and is a writer and artist based in Sydney.