Pascale Marthine Tayou’s Material World

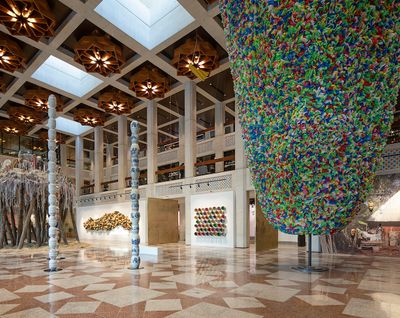

Exhibition view: Pascale Marthine Tayou, LOBI LOBI, Cultural Foundation, Abu Dhabi (3 May–26 November 2023). Courtesy Cultural Foundation, Abu Dhabi.

Around the mid-1990s, Jean Apollinaire Tayou abandoned his law studies at the University of Yaoundé in Cameroon to become an artist and changed his name to Pascale Marthine Tayou.

Marthine is Tayou's mother's name with an added 'h', and Pascale is their father's name feminised. 'I wanted symbolically to underline that there is no comparison between the genders, that there is a form of fusion between people,' the artist said in 2022. 'Of course, there can be a difference, but it is important that there is the fusion of these differences.'1

This notion of fusing differences encapsulates Tayou's practice. As a widely travelled cosmopolitan based between Europe and Africa, the artist creates fluid and transcultural compositions out of ancient and contemporary forms and references.

Tayou's current survey at the Abu Dhabi Cultural Foundation foregrounds this fluidity with an exhibition title, LOBI LOBI (3 May–26 November 2023), referring to a Lingala word describing the day before yesterday, the day after tomorrow, and soon.

Casting an open net between continental shores is Welcome Wall (2023), a series of LED welcome signs in African, Arabic, and South Asian languages installed on a large window at the institution's entrance.

Among these signs are titles of works inside the space, like Plastic Bags (2023). This monumental hanging chandelier of plastic bags indicates the materialist approach that Tayou takes by exploring informal economies as communal sites bridging local, regional, and global cultures.

The video installation Fantasia Urbaine (2007), screened on seven monitors on one wall, anchors this aspect of Tayou's practice. Each screen shows footage from a 2007 parade Tayou organised in Douala, Cameroon, during the Salon Urbain de Douala, a triennial festival of public and contemporary art.

Parade participants were street vendors known as sauveteurs, from the French for 'saviour', describing their ability to sell things people need, from clothes and medicinal products to repair services. As a protest against the Douala municipality's plan to remove sauveteurs from the neighbourhood of Akwa, Tayou's intervention honoured their role within society.

Tayou worked as a sauveteur for years after leaving university. His background feeds into a practice that turns salvaged objects into sculptures like Colorful Calabashes (2014), a wall installation of calabashes sourced from B Market in Bafoussam, Cameroon, strung into a cloud-like plume.

Similarly, Coloris (2022) comprises 53 cement-caked buckets used during the construction of Tayou's house in Cameroon, now covered with shades of glitter and lined against the wall like a sculptural spot painting.

Two of Tayou's distinctive, standing crystal figures, Sauveteurs/Couple de supporters (2012), measuring 1.3 and 1.5 metres each, are positioned in the same gallery as Fantasia Urbaine. Adorned with plastic beads and other accoutrements, one wears a plastic floral headdress and the other dons a multicoloured wig with a plastic horn slung over its shoulder.

Ancient legacies are never far from Tayou's compositions, but they are always integrated into a tangible present.

These crystal forms symbolise ancestral spirits in Tayou's sculptural universe. In LOBI LOBI, crystal masks hang from an olive tree in Arbre de vie (2015), while for Mask (2019–2022), ten faces line one wall, each adorned with objects like Mickey Mouse ears and wooden earrings shaped like Africa. Integrated among them are wooden visages from Masque Bronze (2019), similarly ornamented with household items such as a scaffolding of blue, green, and yellow hand brushes on one.

Ancient legacies are never far from Tayou's compositions, but they are always integrated into a tangible present. Take Fresque Bantu (2021), among the artist's towel 'paintings' that reference Bantu, a linguistic subgroup that historically migrated from West-Central Africa to the south and east of the continent.

The two-by-two metre panel is sectioned into eight parts, each defined by a differently coloured hand towel into which colour-blocked forms of figures and animals have been appliquéd.

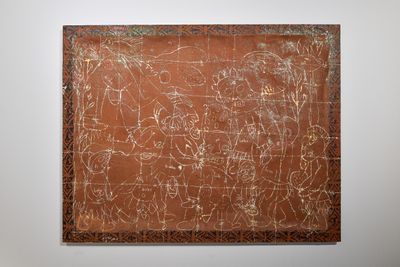

While reaching into the past, BoboLand 1 (2013) simultaneously casts visions of the future. The composition is part of a series showing childlike figures scratched into panels coated with red earth, which the artist associates with memories of their mother sweeping the yard. Rooted to a fictional story of a boy who dreams of going to the moon, these images, as Tayou describes in the wall label, are 'portraits of memories and of this sacred space that "carries" everything'.

That sacred space where all things converge is monumentalised in the shrine-like Home Sweet Home (2011), a forest of tree trunks on a hay mound base, topped by a plume of cables, birdcages, and microphones.

Small, carved and painted wooden flâneur figures are found among their entanglements. These wanderer figures, whose cosmopolitan styling evokes the suited, sartorial swagger of Congolese sapeurs, are among the many signals that Tayou integrates into their compositions to connect ideas of culture and adaptation across time and place.

Bendskin Cotonou B (2014), for example, is a bicycle holding a stack of cardboard boxes on its back and a small television. A video shows benskineurs in rural Benin, informal motorbike couriers and taxi drivers in West Africa who navigate winding routes while carrying heavy loads, including passengers who bend their bodies to even the spread. Hence 'bendskin', which also refers to a Cameroonian form of dance.

Garden House (2010) creates another intersectional form with seven wood panels structuring an enclosed space. Each is printed with images of forests, wooden shacks, and dirt floors, and hosts found objects on their surfaces, including birdhouses, corrugated iron sheets, and white plastic garden chairs.

This deconstructed shanty town, based on those Tayou has observed in Benin, Cameroon, and Japan, is positioned under The Falling House (2014), two model houses hanging upside down from the ceiling made from photographs printed on wooden panels, with corrugated iron roofs. When shown in Tayou's 2015 Serpentine Gallery show in London, Boomerang, the artist called the installation an embodiment of the human race.

These embodiments extend to series like 'Colonne Pascale' (2010–ongoing), which stacks pots and vases from around the world, reminiscent of Constantin Brancusi's Endless Column (c. 1938). Five new columns commissioned for the Abu Dhabi Cultural Foundation's outdoor fountain include two composed of clay pots from an artisanal pottery studio in the U.A.E. where craftsmen blend South Asian and Arab designs, and three created from steel pots painted with patterns characteristic to the Gulf.

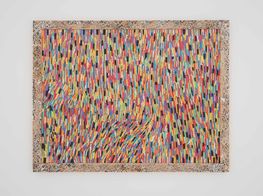

These columns speak to Tayou's resolute engagement with the world as a material space formed from the handiwork of all. Nowhere is this more clearly expressed than in the 'Cloth Paintings' series (2013), which Tayou has described as 'portraits of the crowd'.

Pieces of fabric drawn from found clothes are patchworked on wood to create undulating collages of colours—from black to green and orange to white—expressing a humanist perspective that evades the flattening universalism of colonial modernity.

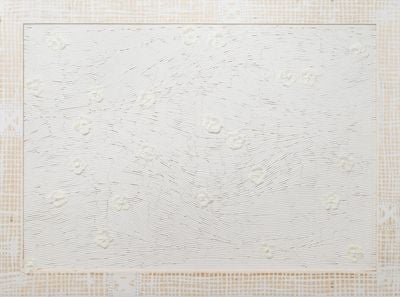

Indeed, while Tayou's forms integrate histories of violence into their compositions, they also seek pathways through these embedded human stains. In White Spirit B (2018), white chalks on wood create a monochromatic surface referencing the artist's Cameroonian education under the French and British educational systems as vestiges of Africa's colonial past.

But while the work visually references whiteness as a power structure, these white chalks, as exhibition materials note, refer to childhood innocence, when the mind is not yet indoctrinated into believing myths of superiority.

Tayou's chalk paintings form a characteristic trajectory in the artist's practice, with compositions like Chalk Fresco E (2014) arranging red, blue, and yellow chalks across a panel to create a 'painted' surface. In LOBI LOBI, these works form a link with BOBO LAND (3 May–26 November 2023), a companion show organised by the Abu Dhabi Cultural Foundation for younger audiences in the same building.

BOBO LAND opens with an installation of giant painted wood chalks, Colorful Thorns (2020), which bear down like stalactites from the ceiling over a hand-tufted carpet printed with a chalk fresco. Arranged on the wall nearby are wooden flâneurs bordering a snaking pathway, around which a wall text points out that, while everyone comes from different times and places, 'we are all on the same voyage towards our dreams.'

Two large collages from the 'Kids Spirit' series (2011) expand on these reveries. Over pages from student notebooks, Tayou has drawn an organic grid of children amid a flow of lines and ladders, while the photographic series 'Kids Masquerade' (2009) shows children wearing cartoon character masks, from Batman to Sailor Moon.

Calling back to the series after which this show is named, where Tayou inscribed the dreams of a boy on red earth, BOBO LAND reminds kids and adults alike that the imagination is limitless. 'Once one dream ends, another is born,' one wall text states. 'Round and round the path takes you, Around the circle of life.'

Of course, Tayou has no illusions that life's spiral is forever harmonious, as suggested by Tornado (2023), which is installed in an external portico like a prologue and epilogue at once. Kite-like diamonds of corrugated metal sheets painted candy colours hang from the ceiling, open to the elements that surround them—like another portrait of a crowd. —[O]

1 Matteo Mammoli, 'Masks, colours, coffee – Pascale Marthine Tayou from Cameroon to the world', Lampoon Magazine, 8 November 2022.