Sharjah Biennial 15 Subverts and Contradicts, Generating Potent Reflections

Helina Metaferia, The Willing (2023). Produced by Sharjah Art Foundation. Performance view: Sharjah Biennial 15, Arts Square (7 February–11 June 2023). Courtesy Sharjah Art Foundation. Photo: Shanavas Jamaluddin.

The 15th Sharjah Biennial is undoubtedly a subversive exhibition. Curated by Sharjah Art Foundation president and director Hoor Al Qasimi, there are moments across this generative curatorial—over 300 works by over 150 artists and collectives across 19 venues—that nudge open the Overton window in the U.A.E., which cannot go unnoticed.

Take Nosferasta: First Bite (2021) by Adam Khalil and Bayley Sweitzer, a short film screened at Bank Street Building, starring artist and musician Oba. Framing the settler colonial project and the nation-state system it spawned as blood-sucking, the story begins on the shores of the so-called New World, where the vampire Christopher Columbus turns a shipwrecked African slave into his progeny.

Fast forward a few centuries, and this progeny has become a Rastafarian in New York trying to renew his U.S. green card. He talks about marijuana releasing him from the trauma of enslavement, amid a euphoric weed-smoking montage that feels eyebrow-raising in the context of the U.A.E., where the drug is illegal even if discovered in a person's system—like with Singapore and Korea—as is, in some cases, its depiction.

In its showing in Sharjah, Nosferasta highlights the non-alignment of legality across global time and space, and the myriad factors that contribute to those divergences, not to mention their interpretation. New York decriminalised recreational marijuana in 2021, the year the U.A.E. marginally relaxed laws surrounding the discovery of certain THC-containing products at the border—landmark moves in both cases.

Such overlaps highlighting contextual differences, intersections, and developments occur throughout Sharjah Biennial 15 (SB15), which departs from the late Okwui Enwezor's thesis for an exhibition he was meant to curate, and whose words form the show's title: Thinking Historically in the Present.

Another example is Isaac Julien's achingly beautiful Once Again . . . (Statues Never Die) (2022). The five-channel black-and-white video installation, presented at Calligraphy Square, stages a conversation between two 20th-century American contemporaries, based on their writings on African art: the white collector Albert Barnes, and the Black queer cultural leader Alain Locke, father of the Harlem Renaissance.

Such overlaps highlighting contextual differences, alignments, and developments occur throughout Sharjah Biennial 15...

Discussions between Locke, played by Moonlight's André Holland, and Barnes, played by Succession's Danny Huston, were filmed at the Barnes Foundation in Pennsylvania. While at Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, a romantically charged interaction between Locke and sculptor Richmond Barthé, played by Devon Terrell, is put into relief by the U.A.E.'s ban of Pixar animation Lightyear in 2022, among a reported 14 countries to have done so, due to depictions of a same-sex relationship.

With instances of male nudity obscured only in full frontal shots, and edited callbacks to Julien's 1989 film Looking for Langston, which pays tribute to queer pioneers of Black American art and culture, the screening of Once Again in Sharjah demonstrates the Sharjah Biennial's willingness to carefully test the lines of acceptability in the U.A.E. for its 30th anniversary edition.

As a conversation with previous editions, it's certainly noteworthy that Thinking Historically in the Present reflects the Biennial's growth and realignment, particularly in the last decade. In 2011, a few SB10 artists and curators were questioned by police after protesting a crackdown on civil unrest in Bahrain, before an installation's removal from a public square due to explicit descriptions of sexual violence prompted reductive accusations of censorship. (The work would've come with a trigger warning, even in America.)

What followed was Yuko Hasegawa's reorientation of the Biennial's focus to the so-called Global South, with a 2013 show emphasising contextual nuances. The Biennial has pursued transnational conversations within a 'postcolonial constellation of the Global South'1 since, establishing itself as lodestar for reframing and rewriting art histories beyond the West. (Al Qasimi, who founded Sharjah Art Foundation in 2009, was elected president of the International Biennial Association in 2017, with IBA now headquartered in Sharjah.)

With that in mind, sections in Once Again filmed in the Pitt Rivers Museum at the University of Oxford, where Locke served as the first Black Rhodes Scholar, are especially poignant when reading SB15 as a statement of intent. Particularly given the Sharjah Biennial's efforts, with Sharjah Art Foundation, to create encounters that decentre the primacy of the Western world and its canons.

Edited alongside shots from Ghanaian filmmaker Nii Kwate Owoo's 1970 documentary You Hide Me, of British Museum storage rooms filled with looted African artefacts, are scenes of a Black curator, played by Sharlene Whyte, roaming the Pitt Rivers Museum's African exhibits. 'It is not a dead society we want to revive. We leave that to those who go in for exoticism', a female voiceover says, quoting Martiniquan politician Aimé Césaire. 'Nor is it the present colonial society we wish to prolong'. Rather, 'it is a new society we must create...'

That call to create a new society is SB15's key inquiry, which remains thoughtfully anchored to its context while pursuing global ideas. Take Farah Al Qasimi's short film, Um Al Dhabab (Mother of Fog) (2023), installed in a green-lit room of the Khorfakkan Art Centre, which aims to correct the British Empire's invasion-justifying characterisation of the Al Qasimi as pirates by remembering them as anti-colonial fighters.

In the film, two young women recover an ancestor's bones from a site earmarked for development, which speaks to the rapid modernisation that has defined the U.A.E. in recent decades. When they rebury their forefather by the shore, his spirit revels in the sands and waters he defended, as bird's-eye shots come into view of terrain ripped up to make way for a commercial megaplex so characteristic of global capitalism.

Um Al Dhabab conjures the tensions between past and future that bear down on the present, as does Once Again. While discussing African art, Locke gestures towards himself when describing those who know this art best. Yet it was Barnes, an anti-segregationist with links to the Harlem Renaissance, who held the artefacts and the means to collect them, highlighting the complex dynamics of patronage, not to mention the intersections of race and class, that have shaped cultural histories through time.

Thus, while Once Again seeks pathways forward, it acknowledges the fraught ground from which the future will inevitably emerge, as does SB15. 'Nothing is more galvanising than the sense of a cultural past,' says Locke in one scene. Even more so when that past has been displaced. But what happens when that displacement is rectified by, or from within, a structure—whether artistic, political, or both—that is intimately enmeshed with the system that produced that displacement?

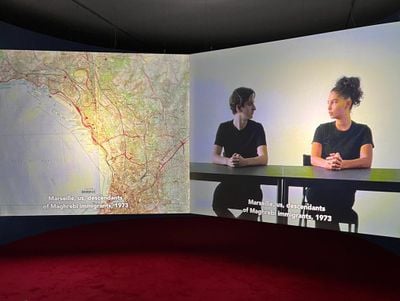

Nowhere is this contradictory entanglement—a catch-22 that resonates across postcolonial and diasporic worlds—more palpable than in Bouchra Khalili's mixed-media installation The Circle (2023). Narrated by two descendants of Maghrebi immigrants in Marseille, a two-channel video tells the story of the Arab Workers' Movement (MTA) and its theatre groups, Al Assifa (The Tempest) and Al Halaka (The Circle), who, with the support of French students and leftists, protested the working conditions of immigrants in 1970s France.

As a conversation with previous editions, it's certainly noteworthy that Thinking Historically in the Present reflects the Sharjah Biennial's growth and realignment, particularly in the last decade.

Through archival images that often pass under a smartphone's lens, The Circle describes the context from which the MTA emerged. Including the 1972 Marcellin-Fontanet decree, which declared only foreigners with a work contract and proof of access to 'decent housing' eligible for resident cards, instantly rendering a cross-section of immigrant labourers irregular in the eyes of the law.

Khalili connects The Circle with The Tempest Society (2017), a video presented at documenta 14 foregrounding immigrant conditions in Greece. An interaction between both works' narrators in The Circle's prologue draws links between Athens in 2016 and Marseille in 1973 and 2022. At SB15, that constellation inevitably pings back to Sharjah in 2023 and the decades-long struggles for migrant workers' rights in the U.A.E., not to mention pathways for long-term residence visas and citizenship for established expatriates.

While recent reforms have moved to address both issues, labour unions and strikes remain illegal across the federation, making a May Day walk-out in 2022 by riders for the U.K.-based food-delivery firm Deliveroo in Dubai, followed by riders for German-owned Talabat that same month, even more notable. Particularly when interpreting The Circle's inclusion in SB15 as a gesture of support.

That gesture is amplified at Kalba Kindergarten, where Gabriela Golder's two-channel video installation, Conversation Piece (2012), features two young girls reading The Communist Manifesto (1848). They ask about different words and phrases, which their grandmother, an ex-militant in the Argentine Communist Party, answers. Questions about class struggle invite an analysis of the battle between oppressor and oppressed in the capitalist system, which often remains hidden, particularly where opposition is suppressed or pacified.

In the context of an authoritarian state governed as a federation of absolute monarchies, where forms of liberalism have been allowed to flourish, the presence of Golder's work feels incendiary and contradictory in equal measure. A daring provocation that magnifies the prismatic complexity of the geopolitical moment and its historical roots.

Take Nosferasta, where fleeting splices of silent film show Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie. In 1936, Selassie accused the League of Nations of abandoning Ethiopia, a League member since 1923, in the face of Mussolini's Italian invasion, despite Italy's violation of international treaties and the League's obligations to peace. But one story in the saga of Western imperialism.

While Once Again seeks pathways forward, it acknowledges the fraught ground from which the future will inevitably emerge, as does Sharjah Biennial 15.

Back then, even powers that engaged with the European nationalist-imperialist system were subjected to forms of colonisation by dint of their non-European status, and as a result, occupy a complex place within the field of decolonisation and anti-imperialism today. Just as ex-colonial Western states, some of them constitutional monarchies, continue to preach democratic liberalism while enacting neo-colonialist tendencies.

Then there are those places and peoples that have been historically caught in between, as articulated in Lee Kai-chung's three-channel film I Could Not Recall How I Got Here (2019) at Bank Street. A story of longing and alienation unfolds in the lives of a Cantonese prisoner and Japanese housewife amid Japan's occupation of the British colony in World War II; an extension of Shōwa-era ambitions to establish a pan-Asian empire, which W.E.B. Du Bois, for a time, endorsed as a challenge to white supremacy.

Thinking Historically in the Present asks what solidarities and futures might be generated from this very world, or the world as it is: a messy entanglement of histories that have produced evolving economic and political systems and cultures that do not always align. Nor could they in this unfolding multipolar century, as states filtering the postcolonial rhetoric of non-alignment seek progress beyond Western paradigms, and grassroots movements arise to challenge them, demanding progress by other means and on equitable terms.

Hajra Waheed's SB15 commission Hum II (2023) pays tribute to such movements. Seven songs connected to women-led popular uprisings across Africa, Asia, and the Americas, have been turned into humming melodies that play within a conical chamber at Al Mureijah Square. Among them are the sounds of 'Baraye', released in 2022 by Iranian singer Shervin Hajipour, in the wake of Mahsa Amini's death at the hands of Iran's morality police.

At Sharjah Art Museum, where Robyn Kahukiwa's monumental red-and-black-figure painting Tihe Mauri Ora (1990) seethes against the subjugation of Maori women under colonialism, Varunika Saraf's We, The People (2018–2022) commemorates civil actions across India's modern history. Among the events depicted in 76 hand-embroideries, is a 1971 protest in New Delhi demanding the release from U.S. prison of Angela Davis, who emphasises international solidarity in an SB15-commissioned documentary by Manthia Diawara.

Ayoung Kim's Porosity Valley 2: Tricksters' Plot (2019) enacts another form of solidarity with a multimedia project at The Africa Institute, which departs from reactions to Yemeni refugees in South Korea.

A two-channel video follows a data cluster treated as malware in a new territory, where an automated biometric model for citizenship becomes both a solution to statelessness and its system of incarceration. It's a utilitarian distillation that finds an affective counterpoint in Gabrielle Goliath's 12-channel sound-and-light installation, These three remain (2023). Abstracting solidarity to its essence, the word 'love' has been isolated from over 1,200 songs and woven into an immersive sonic embrace at the open-air Bait Gholum Ibrahim.

In its mapping of histories, SB15 foregrounds the entanglements defining the world as a shared historical space. Hassan Hajjaj's documentary film Gnawa Capoeira Brothahood (2022) at Bait al Serkal, explores the roots of two communal dance and musical traditions in the slave trade: Sufi-Islamic Gnawa and Brazilian Capoeira, a martial art originally disguised as dance by slaves.

While Hyesoo Park's A Man without a Country (2023) blurs the boundaries defining seemingly clear-cut geopolitical and ideological divides at Bank Street. A wall of questionnaires filled out by North Korean defectors to South Korea reveal, at times, disillusionment to their new circumstances, whether due to their othering as outsiders or the struggle to survive in the capitalist system.

Works like these, which confront the intricate particularities of material enmeshment in order to open up potent reflections around what Enwezor described as 'all the world's futures', resonate with Once Again. 'For us, the problem is not to make a utopian and sterile attempt to repeat the past, but to go beyond,' says Whyte's character in the film, quoting Césaire.

While no biennial could be expected to answer what that 'beyond' might be, Thinking Historically in the Present has gathered a remarkable assembly of works to think—and feel—through the true density of its foundations. —[O]

1 Hoor Al Qasimi, 'Curatorial Statement', Guidebook for Sharjah Biennial 15: Thinking Historically in the Present (2023): p.8.