Farah Al Qasimi: 'So many aspects of the world I photograph are deeply universal'

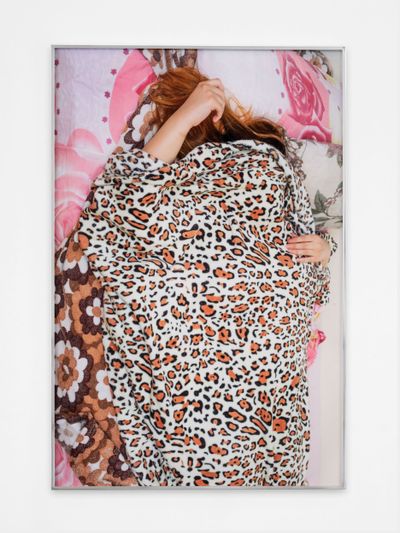

Farah Al Qasimi. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Andrew J.S.

Farah Al Qasimi. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Andrew J.S.

Writing in 2020, artist and writer Christopher Joshua Benton described Farah Al Qasimi's 'brand of Gulf Futurism' as 'less ironic than her contemporaries, but probably more complex—offering up a sentimental, nostalgic, and critical window that is world-building'.

Coined by artists Sophia Al-Maria and Fatima Al Qadiri about a decade ago, Gulf Futurism, broadly speaking, describes the cultural shifts prompted by the rapid modernisation of the Gulf states into what Al Qadiri described as a 'consumer-culture robot desert'. Al Qasimi's images, a patchwork of forms and intersecting perspectives, both encapsulate and expand this contextual milieu in the U.A.E., where tradition has become enmeshed with mall culture, technological development, and free-market globalism.

Dragon Mart LED Display (2019), for instance, is a maximalist still life in which an entanglement of L.E.D. light tubes and plastic flowers in shiny white vases glitter amid a backdrop of mirrored surfaces, reflective walls, and fairy light cascades. The work extends from 'DRAGON!', a series commissioned for the Global Art Forum in 2017, which focuses on Dubai's Dragon Mart, among the largest hubs for Chinese products outside China.

'There are so many layers of aesthetic translation happening there,' Al Qasimi has said of the mall, with its Chinese-produced Gulf furniture adapting classically European styles. 'So there's a sort of broken-telephone game of cultural interpretation happening.'

Dragon Mart LED Display appears in General Behaviour, a survey of Al Qasimi's photographs and videos from 2012 to 2021 at the Cultural Foundation in Abu Dhabi (11 March–20 September 2022), alongside 'Closed Kiosk' (2019), a minimalist series zooming in on monochrome fabrics used by Dragon Mart vendors to cover their booths.

General Behaviour unfolds the broken-telephone game of translation that Al Qasimi describes across images that treat landscape, portraiture, and still-life pictorial traditions with a 21st-century perspective. Whether in Old McDonald's (2014), the imprint of an absent McDonald's 'M' on a sand-brick wall; or M Napping On Carpet (2016), the bird's-eye view of a woman in a beige floral tunic lying on a beige floral carpet in shiny, hot-pink-to-burning-blue heels.

Across Al Qasimi's exhibitions, images blown up into wallpapers form backdrops for photographs arranged like notes in a graphic score—a compositional device echoing Aviary (2019), a photograph of a woman viewing a faux indoor desert complete with live birds and wallpaper sand dunes.

There's a claustrophobia to these compositions, in which artifice and reality are crammed into sharply lit and hyper-colourised frames. And yet, Al Qasimi choreographs these densities into formal explosions that paradoxically create room for images to breathe.

Take Living Room Vape (2016). A clash of interior details frames a man in a white kandura sitting on an embossed periwinkle sofa, with a European painting of a stone-arch bridge framed in gilded gold behind him.

The room's blue walls are mostly concealed by such adornments, including a woven wall tapestry with red velvet borders. A Persian carpet covers the floor, and a table hosts a circle of vases, one bursting with a multi-coloured bouquet: every pattern reflects the Silk Road's transcultural legacies. To one side, a woman reaches out a hand as her metallic, purple-blue robe expands. Amid the detail, the man's face, the image's focal point, is obscured by a perfect plume of vape smoke.

Witty sleights of hand like these define Al Qasimi's compositions, as seen in Shower with Lux Soap (2018), where a hand emerges from the top of a white shower curtain wielding a bar of pink soap, like a soft invocation of Hitchcock's infamous Psycho shower scene.

Lux soap reappears in Lux Soap in Blue Bathroom (2018), a close-up of a blue ceramic sink with pink soap nestled in its corner groove. In General Behaviour, the image is shown with Orange Soap in Orange Bathroom (2018), which catches peach soap melting into a niche—part of a series elevating both the still life and monochrome traditions to a sublime and nostalgic domestic kitsch.

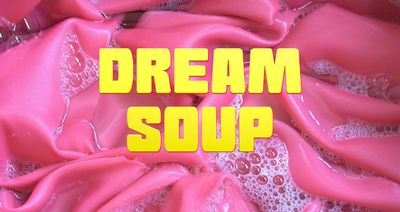

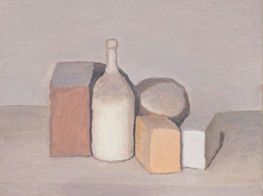

Also on view is Perfume (Obama, Lovable, Flawless) (2018), a still life of perfume bottles arranged on a green-marbled bathroom ledge, like a technicolour Morandi. The work connects to Dream Soup (2019), a video tracking the production of perfumes in factories and stores around the Emirates, screened in a room with lavender Rococo furniture and carpeting.

'I've been trying to nail down what a "Gulf aesthetic" actually is, and I don't think you can,' Al Qasimi said in one interview, pointing out that looking at the displays at Dragon Mart is part of it—'I always go there when I want to think about where I am.'

The same could be said of Al Qasimi's practice in general, where the subject of the Gulf expands into a dynamic, maximalist, rhizomatic entanglement that cannot be contained, much like the artist's practice.

In this interview, Al Qasimi reflects on the personal significance of General Behaviour, while introducing Surge, a recent solo show at François Ghebaly in Los Angeles (14 May–18 June 2022), which marked the opening of a horizon in the artist's practice.

SBYour exhibition General Behaviour is named after a video screened on Bidoun, for which Sophia Al-Maria wrote a beautiful introduction, and the show includes a still from the video depicting a line of young girls performing at a festival, Khaleeji Hair Dance (2020).

What's the meaning behind the title?

FAQGeneral Behaviour is a title I took from a pack of stickers meant to educate children on good Muslim behaviour. I thought it was such a great title because there's a generality to how I work; sometimes things are hyper-focused and research-heavy, and sometimes it's just observation. As the Cultural Foundation show is almost a survey of my everyday practice, it felt apt.

SBAs you said, this is almost a survey, and it really highlights your distinctive approach to photography. How would you define your practice?

FAQBeyond wanting to engage with the excessive imagery around us, I'm interested in layers and windows as someone who is of the generation that suddenly had access to the internet. I am very aware of how it acts as both a window and a black hole connecting you to the rest of the world while removing you from your surroundings.

We're never free from being consumers, as we're always being targeted ... My work is a space where I can be critical of that language.

I think the images are meant to act the same way; they suck you into this other universe and act as a tonic for the ordinary. At the same time, they contain an alternative ordinary. I think the layering reflects how we are constantly being tugged in different directions by advertisements and algorithms, physically and virtually.

I live in a neighbourhood where I look out the window and see billboards. It's depressing, but also comforting; the advertisements don't know who I am and whether I am their target audience, while my Instagram feed knows the microscopic details of what I said yesterday.

We're never free from being consumers, as we're always being targeted, and our money is being sought after. My work is a space where I can be critical of that language. I'm not trying to sell you anything but to give you an almost Disneyland-like experience that is transformative and takes you somewhere. It's a physical manifestation of the desires capitalism harnesses and exploits, but it doesn't ask for anything besides your attention.

SBAre there particular artistic influences that have informed your approach to image-making?

FAQI'm a big fan of Jan Groover and Paul Outerbridge, photographers who showed us the magic of a still life. I watch a lot of cartoons and horror films. I love Maya Deren and the choreographer Blondell Cummings, who made a lot of beautiful dance pieces that took place in domestic settings.

Also, Sophia Al-Maria, whose writing has been so important for me as a window to understanding my own experience. And Elle Pérez, a dear friend and incredible artist, whom I love talking to about the problems and joys of photography as a medium.

SBThere's always a witty sleight of hand in how you stage your shots, as seen in photographs like It's Not Easy Being Seen (2016), where an arm in chroma-key green gloves in a chroma-key green room reaches for a tipping vase.

There's a musicality to it; a sense that each photo was a decisive moment that balanced intention with the serendipity of an instance, like the black cat at the centre of Furniture Market, Stray Cat (2018).

FAQMost of the time when I work, I am not seeking a specific moment, but when it comes, I know it. No matter how you're working, there's always a moment something clicks. Either the person feels comfortable, or you've figured out a gesture that makes sense; something is right and you just know.

It's funny because I am very vocal when working with others, I feel like I am a 1990s rom-com version of a photographer and I don't even notice it. Vocalising is so important because you are reflecting someone back to them—it's a conversation.

In the image you mentioned, I was photographing this window when the cat came along. A person working at the cafeteria next door saw that I was trying to get the cat's attention and brought out some chicken to keep the cat in the frame. It was such a sweet gesture and totally unplanned.

SBYour voice is especially clear in your staged images. In General Behaviour, a line of portraits of men features one of your dad, Baba at Home (2017), set against a cascade of draping curtains.

FAQYes! I wanted to photograph him like a painting of a Dutch nobleman. I took that photograph minutes before I left for the airport to go to graduate school. I feel lucky he let me do that.

He worked in government for most of his life, so he is very used to being photographed. But every time I say I'm going to take his picture, he immediately smiles—it was hard to get him to not be prepared or appear guarded.

SBThe way you approach your compositions really suits the space of the Cultural Foundation, with its intersecting sightlines, architectural styles, and angles—a postmodern unity.

FAQI love that space. It was one of the first spaces in the country dedicated to arts and culture and I grew up playing piano recitals there. The hall where my exhibition is located is iconic—its patterned marble floors are burned into so many people's memory.

I went there all the time as a kid—my mom's office was also there because she worked for the National Archives as a historian. Basically, anyone who did anything related to culture had their offices in the Cultural Foundation. There was a library, a café, and they hosted book fairs; it was one of the few free places where you could spend your spare time in the 1990s.

To have a show there is like having your art on a highway billboard. People visit the Foundation for so many reasons, and because it's free, it gets foot traffic and audiences who are not necessarily there for the exhibitions. I think that's really valuable, to be able to happen upon something without seeking it out. As an artist, it's kind of the dream audience. You're not just making work for a bubble.

SBIt's amazing you played piano there, given one of the video installations in the show, Alone in a Crowd (King of Joy) (2020), is of you playing the piano dressed as a clown cycling through a range of emotions.

FAQI didn't even make that connection until the show was up! It's so interesting because the piece is so much about the performativity of emotion. But I wasn't necessarily thinking about playing the piano as a kid; I was so nervous about messing up whatever basic Mozart song I was playing.

There is something to be said about performativity and identity, and how they come together in your youth. I don't know many people who had to play at piano recitals or be on stage as a kid and didn't dread it. That's how I feel when I'm in my work—overly visible and vulnerable.

It seems fitting to me that this film should screen in a place that I associate with a certain kind of vulnerability—a fear of being seen. Even though I'm dressed as a clown, it's just me. It's my face and there's no script to it. I sat down and played the piano in the house I grew up in, on the piano where I learned to play basic Mozart songs.

Making the video, I thought about music as a language and how to translate different points on the emotional spectrum. Not only through sound, but also through gestures and facial expressions, because in the video, you can only see my face.

People were unsure if I was actually playing the piano when they saw the video, but I don't think it really matters. Looking at it now, I realise that the experience of sitting with the discomfort of seeing myself emote is where the work is located, or where the discovery was.

SBAnd the piano was a conduit to that discovery?

FAQDefinitely. It literally moves from major key to minor. Happy to sad. Joyful to tragic.

SBWhich is reflected in the range of emotions you express as you play.

FAQWe all know that tragedy and comedy go hand-in-hand—you know, like those dramatic masks that are always shown in pairs.

SBFirst as tragedy then as farce?

FAQYes, and it turned into something bigger than it was. King of Joy was an important exercise in restraint for me because I often try to hide behind affect, and that's something I'm trying to challenge myself more on. How do you know when to strip things down, to stop and pull back? Sometimes it's hard to know when to stop.

When I was an undergrad, I studied music and fell in love with painting. I was in this painting class where I was making these huge, laborious paintings about my O.C.D. One day, I made one that was really small, and my professor at the time was like, 'This is it. You cracked the code.'

There was something about not labouring over it, not being precious; just making something with a life of its own. I think that clarity is rare and it's often out of view.

Most of the time when I work, I am not seeking a specific moment, but when it comes, I know it.

I still have trouble watching King of Joy because I don't like looking at my face, even when it's covered in clown make-up—especially as a photographer who sits behind the camera. For most of my work, I make sure my voice is present in subtle ways, but it's right there in this case.

SBIt's true that your photographs, despite their decisive compositional voice, have this quality of removal. Your gaze feels almost diffused through the maximalism of your compositions.

FAQIt's this compulsive thing I do; at this point, it's pathological and I have to confront it. But it's interesting to look back at my work and think, it's not voiceless—it's there, it's loud.

In my show at François Ghebaly, my narration is in the video; I voice this African land snail that is singing a song at the end of the film, but that's about the extent of my physical presence.

SBThis is where we get to your recent show Surge, which departs from Tomoharu Katsumata's 1975 film version of The Little Mermaid. Could you introduce the show and the video you just mentioned?

FAQThe show takes the narrative trope of The Little Mermaid as a metaphor for the environmental impact of coastal city economies. I chose the title of the show randomly—I thought—before Sophia Al-Maria reminded me that it's the title of one of my favourite Etel Adnan books.

The short video I just mentioned is also titled Surge (2022). Three voices narrate it. It starts with the voice of a human expressing their fear of water and the ocean, and then it segues to a mermaid who talks about her fear of land.

Then it cuts to a third voice, which is an African snail that is considered a pest. People kill these snails by dumping them into buckets of salt. The snail sings about longing, and being seen and acknowledged by someone it loves. It's never said whether the character is a human or another snail.

It's my voice singing in the work, as I wrote the music for the film, but it's transcribed a couple of steps up, so it sounds like what a snail might sound like, I think.

SBIf I were to compare Surge with General Behaviour, which shows your work up to 2021, it seems Surge, in 2022, marks the opening of a horizon in your practice.

FAQI would say that. This work felt so new and unfamiliar to me. I was home, on winter break from my job, and the Omicron wave had just hit.

I hadn't been home in a year, and because of the mandatory quarantine in the last few years, I hadn't seen anyone but my family for so long. I was so excited to be reunited with friends; to be photographing and making collaborative work. That possibility was crushed when I realised the risks.

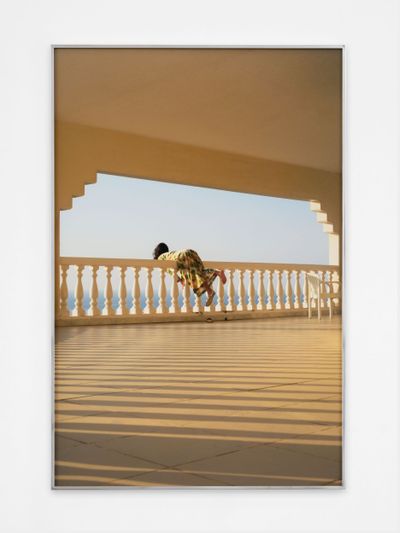

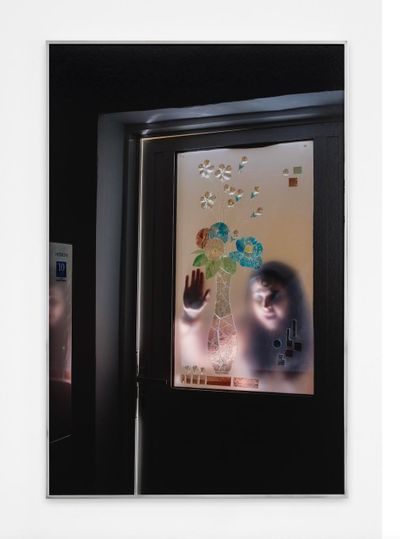

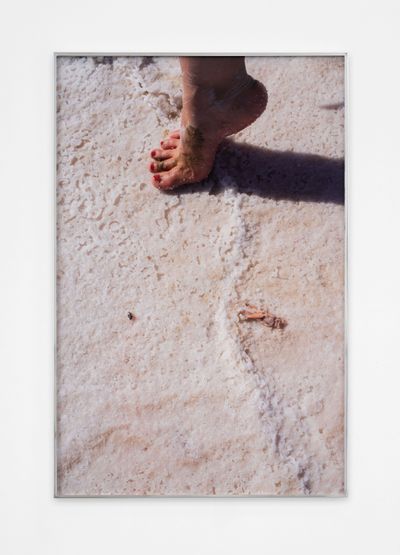

So, I spent a lot of time on my own, photographing in public spaces while masked. Some were taken in friends' houses, but I think there's a sense of isolation, sadness, and loss in a lot of the photographs. It really felt like everything was on pause.

I think my past work had a real commitment to colour and exuberance. I felt like this was muted in Surge, but it feels more like a shift than a loss.

SBThat makes sense because the work you've done in commercial spaces, for instance, condenses the maximalism of commerce into the frame—it's like you dive in.

But with Surge, this idea of keeping a distance comes through in a pulling back. Could you talk about that?

FAQI think it's pictorial space; there's not as much crowding because the world isn't happening as much, or as closely together. There's more spatial isolation and single figures within a frame.

There are a lot of isolated women in enclosed spaces, and one giant wallpaper of a man in a lobby, examining himself in a mirror. It was a nod to the Little Mermaid trope—all these isolated, single, ostensibly female figures reaching toward or hidden behind something.

Often, when I'm working in settings with multiple people and there is a lot of play, gesture, and choreography, there is also a lot of spatial build-up in the work. A lot of activating of foreground, background, and overlap.

Some of that is present in these new works, but a lot of the works in Surge hint at the experience of movement through the world; of being afraid of the possibility of connecting with others because closeness is suddenly synonymous with danger.

This period has taken a massive psychological toll on everyone, and we haven't really started to process what it means. Only by looking back at the photographs, I was able to see this kind of isolation and reaching—a hope that is fragile but present.

SBThat brings to mind an image in Surge of a snail resting on a woman's arm, Woman and Snail (2022), and the exhibition's narrative.

You have a mermaid longing to be loved by a human, and a snail longing for love that everyone wants dead. There's a potential for solidarity between the two.

FAQYes. There's a montage of TikTok and YouTube footage in Surge, the film, which is basically people showing you how to kill a tonne of snails at once.

It's funny, I never felt very sympathetic towards snails until I met Gary the snail, and Dandelion, his sibling. It's interesting to think about how we value certain types of life; so many species are regarded as pests because people illegally bring them into environments where they shouldn't naturally exist.

This has to do with humanity's impact on the natural environment: we set up hierarchies of life that are generally convenient for money-making.

There are many different ideas that come together in Surge, but ultimately, it's asking: who deserves happiness, and how do we measure empathy?

This critique of value systems has never been at the forefront of my work before, but it's something I have thought about for a long time. I've been a vegetarian for 11 years, and I grew up in a household that deeply values animal life and often took in strays for rehabilitation or rehoming.

A couple of years ago, I also stopped eating fish, which coincided with me watching Finding Nemo (2003) for the first time. I got weirdly emotional about the thought of catching fish.

The late comedian Mitch Hedberg talked about how catching fish must suck for the fish. When they're too small, they get thrown back into the water. He said, imagine showing up at work and someone says, 'Hey man, you're late again, where were you?' And you're like, 'Oh, I got caught again.'

Thinking about fish having their own ecosystems, communities, and lives, one of the songs in the film repeats a line from the Nirvana song 'Something In The Way', which is from a secret track on Nevermind from 1991. It says, 'It's okay to eat fish / Cause they don't have any feelings,' and I repeat that line over and over in the film.

So there are many different ideas that come together in Surge, but ultimately, it's asking: who deserves happiness, and how do we measure empathy?

SBIs there a broader narrative here about the patriarchy, insofar as it is defined by the lack of recognition of certain beings?

FAQI wasn't necessarily thinking about it as a patriarchal influence, but I do think the message can be distilled to this relationship between desire and danger. The first Little Mermaid cartoon that came out in 1975 by a Japanese animation studio stayed true to the Hans Christian Andersen version, in which Marina—the mermaid—dies at the end.

Her sisters and her little dolphin friend beg her not to throw her life away for this loser prince who forgets about her the second another princess comes along, but she doesn't listen. She has the option to kill him or to die and she chooses not to kill him.

It's sad and I thought about this as a direct metaphor for what happens when, as a society, we want more. More capital, more progress, buildings, infrastructure, fresh water—things that come at a price.

For example, there are so many places in the world where beachfront properties are highly sought after. Where the possibility of selling villas is more important than the health of coral reefs that are eradicated to make way for the beachfront. And so, these ecosystems die—incredibly complex webs of life, nourishment, and balance.

I tried to imagine and give voice to the ecosystems upset and eradicated by these drives for economic gain. Of course, it's a cartoon-like voice; but it's still a voice.

SBI'm reminded of the master-slave dialectic, which describes the violence of modernity.

To complete the dialectic, Hegel wrote, individuals who encounter one another have to engage in the negation of both self and other to attain true self-consciousness. If that doesn't happen, one person is left negated; it's an idea you could relate to the notion of othering as a mode of consumption.

FAQI think you have to define something as 'outside of yourself' to justify its consumption. Photography is a useful tool for that if you think about how it aided eugenics and colonialism for so long. This idea of literally objectifying something so that it is not of you, nor part of your experience, is where cartoons come into play as tools for empathy.

The existential gymnastics we do to justify supremacy over other life forms continuously amazes me.

I grew up with 1990s Nickelodeon and anime like Lady Lady!! (1988). Princess Mononoke (1997) was my favourite movie as a teenager and SpongeBob SquarePants is still one of my favourite cartoons ever, for many reasons. I also love The Muppet Show from the 1970s, when it was still Jim Henson.

Cartoons have been formative for me, even as an adult. I return to them because they teach me about seeing the world on a smaller scale and understanding there are life forms I cannot communicate with. And just because they are unlike me, it doesn't mean I have supremacy over them.

It's a scary time to be alive, but when was the last time it wasn't?

I've photographed in falcon hospitals before and have looked at falcons that have been incapacitated to be harnessed as hunting animals. These are wild birds of prey, and now they have passports. I've spent time with cows and horses for my work, with all kinds of birds and fish, and the existential gymnastics we do to justify supremacy over other life forms continuously amazes me.

That's also a huge reason why I am not a meat eater, let alone the meat industry's insane cruelty, corruption, and carbon footprint. But it's this idea that if you are unlike me, I can exercise control over you that is so particular to individualist identity politics and post-capitalist thought.

It's really sickening and a hard thing to contend with, as someone who needs to engage with these principles to survive. It's also an ancient design to drive wedges between people and eradicate their natural tendencies towards empathy and connection. It's a scary time to be alive, but when was the last time it wasn't?

SBI'd love to ask, the image of the three women in pastel dresses, Salt Lake Sirens (2022)—did you stage this? It's a perfect shot!

FAQNo, that wasn't staged, and I'm so glad you asked because you never know, right? That's why I love photography as a medium, because the world is already there. It's already bizarre and beautiful and all these things are already happening.

Sometimes I do author images by creating the right circumstances to make a photographic moment happen. But for that moment, I drove 45 minutes to the outskirts of Abu Dhabi, where there is a salt lake from the brine in the seawater getting pulled to the surface.

There were three young women who were taking pictures for their Instagram accounts and they looked as if they were about to go to a party. They looked amazing; beautiful and glamorous, colour-coordinated in perfect pastels. So I asked them if I could also take their pictures, and they said, 'Sure'.

I was so grateful they allowed me to do that. I wanted to send them the pictures, but they were like, 'No, we're good!', so I don't have their information to find them. Normally, if I photograph someone in public, I try to get the work back to them. But they were like, 'No, we have the Instagram version.'

SBI first encountered your work, specifically the Dragon Mart images, in 2017 at the Global Art Forum, which tends to draw—whether directly or indirectly—on the often fetishised concept of Gulf Futurism.

Thinking about the gaze and the history of photography, how do you relate to how different audiences and publics look at your images: from what they see to what they expect from them?

FAQI think their universality is inherent because much of the work has to do with growing up in a post-internet world and using the internet to access cultures beyond your own. So many aspects of the world I photograph are deeply universal and hint at migration beyond borders and oceans.

The images are from my own experience; my mother's family are Lebanese-Americans who emigrated in the 1950s. My father is Emirati, but he also came to the U.S. to study and spent a lot of his life outside the U.A.E.

If people are unable to see past location at first glance, it's not my responsibility to explain the deeper ideas, because my target audiences—who are the people in the work, the people the work is about—will have that understanding when they see it. It's interesting how people from different backgrounds come up to me and say, 'This image reminds me of Sundays at my grandmother's house in Mexico City'—or Manila. Anywhere.

There are many reasons why that is, but I am more interested in the magic of it. I think the words 'aesthetics' or 'aestheticise' get a really bad reputation, often because they've been used flippantly to talk about serious things. But aesthetics can also be a window into a longer conversation, where we start to ask deeper questions that stem from our understandings of beauty and desire. —[O]