The Space Between: A Century of Korean Art at LACMA

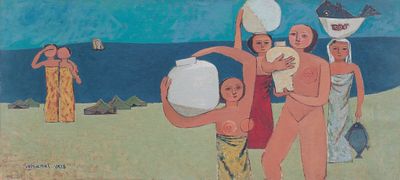

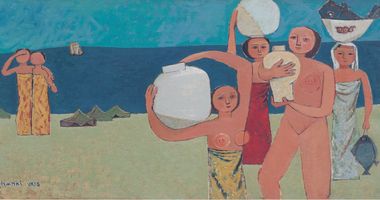

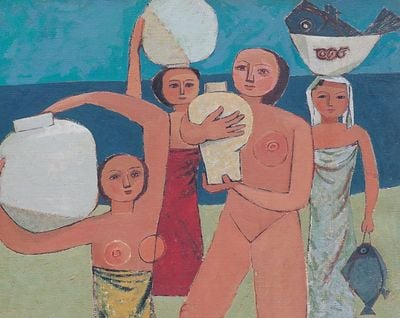

Kim Whanki, Jars and Women (1951) (detail). Private Collection. © Whanki Foundation·Whanki Museum. Courtesy Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

With more than 130 works by 88 artists, The Space Between: The Modern in Korean Art, which opens at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in September (11 September 2022–19 February 2023), is an ambitious showcase that aims to illuminate a particular art history.

Curated by Virginia Moon, the museum's associate curator of Korean art, the exhibition spans the better part of a century, with its curatorial timeframe of 1897 to 1965 broadly associated with the era of Korea's modernisation.

From the final days of the Joseon dynasty at the end of the 1800s, through confrontations with Japanese imperialism in the early 20th century, to the ways Korean artists incorporated the incursions of industrialisation from afar, the exhibition lays out a detailed picture of one culture's vital transformations.

In curator Moon's words, the exhibition is most significantly about 'resilience'. It covers times of intense historical turmoil, representing not only shifts in political power in Korea, but new definitions of national identity and the cultural practices that expressed it.

But while it's one thing to arrange a chronology according to monumental, globally recognised chapters in Korean political history, The Space Between offers a view of the affective, lived experience of perseverance in the often-violent encounters between tradition and tumult. 'Memories of shame, insecurity, hardship, and the separation of families still linger for the older living generation of Koreans,' says Moon. 'After all, the end of the Korean War in 1953 was only 69 years ago.'

As always, the historical is personal. Indeed, the 'modern' cannot be conceived only in terms of time. No map of the category can cover the variegations and innovations of the creative work of people thrown under the mechanics of the age, especially when it designates the rise of global industry according to the Western model, and all its implications for the 20th century's realisation of aesthetics, politics, and modes of subjectivity.

Moon is well attuned to the subtleties and interplays between individual and communal art-making and the enormity of global transformation. 'I firmly believe that within the small population of active artists in Korea during the modern era, regardless of medium, there were exchanges and conversations,' she says.

At the time, ideas from the Western world were being transmitted into Korea indirectly thanks to students attending art schools in Japan, which did not exist in Korea during the Japanese occupation from 1910 to 1945. Accordingly, The Space Between is organised into five distinct sections that indicate without simply re-iterating this historical timeline.

'The Modern Encounter' covers the final days of dynastic rule, when the last two Joseon kings faced an international future by declaring Korea an imperial state. At the time, photographers from Japan were invited to create a visual record of Korea's changing situation.

This influx of photography was to make a lasting impression on Korean culture, though it was not initially accepted as an art form. Traditional ink painters like Kim Eunho eventually modelled the medium's hyperrealism, as reflected in works like Portrait of King Sunjong (1923), which is based on a 1909 photograph.

In 'The Modern Response' section, tradition gives way to the imposition of Japanese colonialism back when artists could only officially learn new styles—many influenced by Western techniques—in Japanese schools.

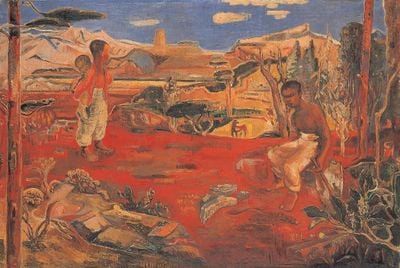

Known as the 'Gauguin of Korea', the late Daegu-based painter Lee In-Sung underwent such an education. His direct figuration and bold primary shades recall the French impressionists, as seen in oil on canvases like Valley in Gyeongju (1934), where vivid reds of a dirt road nearly overtake the people who wait alongside it.

Moon says that some rigid art categories from the colonial era remain in effect today, particularly in exhibitions of modern art. As such, The Space Between brings together photography, sculpture, ink painting, and oil painting in a multi-disciplinary fashion.

Likewise, it was only relatively recently that sculpture was embraced as a fine art medium in Korea, Moon says. Breaking with the convention of associating the medium with Buddhist religious iconography, the show includes an untitled abstract sculpture by the Korean-American sculptor John Pai from 1963.

The work's clear prioritisation of form over representation attests to the curatorial attempt to expand the canon and connect aesthetic sensibilities and movements between the East and its diasporas in the West. This drive for transcultural connection is emphasised in the third section, 'The Modern Momentum', which unpacks an unbridled vibrancy of modern art activity that accelerated and came into its own in the wake of the colonial era.

Here, works by painters Kim Whanki and Park Soo Keun both recover the natural landscapes of traditional painting and imbue them with modern stylism—the former with richly hued abstraction and the latter with elegiac, thickly outlined forms.

These exhibitions reflect an effort by the museum to enrich Los Angeles' embrace of its Korean community while furthering the global conversation on contemporary art...

Non-traditional media also became more widely deployed during this time, and new ideas percolated. Quac Insik, who experimented with brass and glass, would become a leading theorist of the Mono-ha movement (School of Things) in Japan and Korea, which focused on industrial materials, claiming that in a loud world it is best to let objects speak. In his glass on panel Work (1962), a bullet hole can be sighted on a gridded glass panel resembling windows in a classroom.

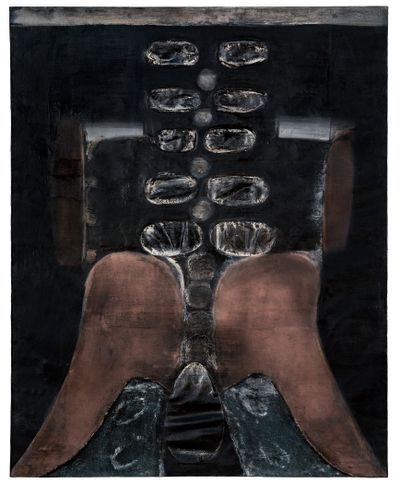

Painted the same year, Park Seo-Bo's oil on canvas Primordials No. 1-62 (1962) elevates disembodied mechanical components into a totemic enigma.

In such circumstances, paradigmatic mutations found singular instantiation. The exhibition focuses on a particularly noteworthy moment in the section 'The Pageantry of Sinyeoseong (New Woman)'. Sinyeoseong refers to the new idealised image of the Korean woman in the 1920s, which informed a 'feminist' movement in Korea for women's relative independence.

Despite being motivated by ruling class men's interest in educating women to produce a more industrially modern society without any substantial shifts in broad power dynamics, the movement produced a unique aesthetic sensibility.

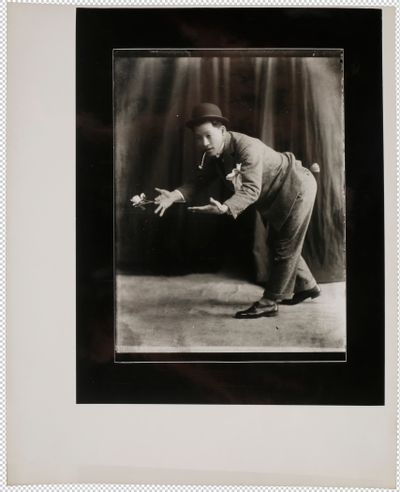

That sensibility is exemplified in what remains one of the most reproduced photos in Korean history, Shin Nak Kyun's 1930 sepia photograph of the famous entertainer Choi Seung-hee, regarded as a pioneer of modern Korean dance, performing a curtsy in a white dress.

Choi's life is emblematic of the complex geopolitics of a quickly reconfiguring world. In keeping with Japan's ambitions for an East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, she championed the concept of pan-Asian dance. Defecting to North Korea after the Korean War, she spent time teaching in China, instructing a generation of professional dancers, and adapting new forms of Chinese choreography that later became Chinese classical dance.

Choi's headlong plunge into modernism anticipates the framing of the exhibition's final section, 'Evolving into the Contemporary'. Presenting the show's most recent works, this section highlights art made after Korea's division into North and South at the close of World War II and the subsequent codification of ideological differences during the Korean War in the early 1950s.

When the Korean government started sponsoring national art exhibitions, some artists perceived these state-sanctioned art shows as perpetuating the colonial conservatism of previous generations. The 1960s Artists Association of recent university graduates, including Kim Dae-wu, Kim Bong Tae, and Choi Gawn-do, rejected governmental structures. When they exhibited their paintings against the walls of Deoksu Palace, in front of the British Embassy, it seemed like the history of Korean modern art reached an inflection point, absorbing the past's fractures while facing the future with confidence.

The Space Between extends the momentum of such future-facing gestures in both scope and intention, as the latest in a series of shows at LACMA supported by The Hyundai Project: Korean Art Scholarship Initiative. These exhibitions reflect an effort by the museum to enrich Los Angeles' embrace of its Korean community while furthering the global conversation on contemporary art and Korean culture's role within it.

'The show is first and foremost for anyone who wants to see Korean art,' Moon emphasises. 'Having said this,' she continues, 'the show is also for the different waves of Korean immigrants to the country. It will be meaningful to share with them these works that were being produced in their country of origin during their lives.' —[O]