KADIST Brings Tradition to Life at Guangdong Times Museum with 'Frequencies of Tradition'

Co-organised with KADIST, Frequencies of Tradition at Guangdong Times Museum upends static notions of tradition, with works by 19 artists, researchers, and filmmakers uncovering histories and futures that charge evolving trajectories.

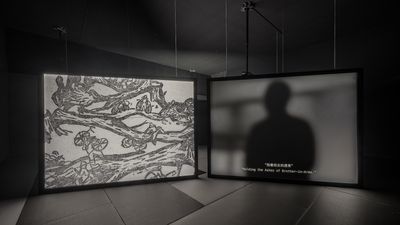

siren eun young jung, A Performing by Flash, Afterimage, Velocity, and Noise (2019). Exhibition view: Frequencies of Tradition, Guangdong Times Museum, Guangzhou (12 December 2020–7 February 2021). Courtesy Guangdong Times Museum. Photo: Luo Xianglin.

Take Ming Wong's sci-fi inflected Tales of the Bamboo Spaceship (2019). The single-channel video opens with a tale of Shaolin monks joining opera troupes along the Pearl River Delta after Qing authorities destroyed their Southern temple: a history of solidarity and resistance between communities that was mythologised by kung fu movies in Hong Kong and Taiwan and stretches from the 17th century to now.

Across the show, compelling remixes re-frame concepts of culture and custom as multi-dimensional and intertwined. In the case of The Heart's Desire (2020), a collaboration with Stella and Roger Nelson, Simon Soon makes pixelated animated GIFs out of archival imagery, including photographs of Cambodian ballet, erotic illustrations for traditional Malay syair poetry manuscripts, and props from 1950s performances depicting an uprising of Chinese plantation labourers in Sumatra.

Curated by Hyunjin Kim, KADIST's lead regional curator for Asia, the exhibition interprets 'tradition as an enchanting liminal space that complicates and pluralises our understanding of the regional modern.' That liminality is embodied in works portraying historical figures as both medium and filter through which customs pass and inevitably evolve.

Hwayeon Nam's multi-channel video installation Dancer from the Peninsula (2019), for example, traces the life of choreographer and dancer Choi Seung-hee. Also known by her Japanese name Sai Shoki, Choi travelled across Europe, North America, Latin America, and—after Japan entered World War II in 1941—China, where she performed for Japanese soldiers, and North Korea, where she defected in 1946.

Narrating a fluid stitching of archival images, contemporary film of a dancer performing in a black box, and emotive close-ups of orchids in (at times ominous) states of bloom, are words spoken in Japanese, Korean, and Chinese drawn from books, magazines, newspapers, and letters written by Choi herself.

Across the show, compelling remixes re-frame concepts of culture and custom as multi-dimensional and intertwined.

We learn of Choi's interest in Asia's choreographic forms, the schools she opened in Pyongyang and Beijing, and her intention to develop a modern East Asian dance, equal to European ballet, that could build bridges across the region.

What emerges is a life forged from the times; a figure of internal and external projections—whether from Western audiences demanding 'authentic' Asian experiences from Choi, fellow Koreans who denounced her as a Japanese collaborator, or her own—as Japan sought to create an empire to rival the imperialist domains of the West, and as Cold War tensions were rising.

Similarly, a series of installations devised by Alexander Keefe commemorate Shanta Rao, among an early wave of classical Indian dancers who opened up traditionally hereditary dance cultures in South India. Like Choi, Rao travelled the world—from Asia, the Middle East and Europe to North America—and became, between the 1940s and 1970s, something of a cultural ambassador for a newly independent India.

Shanta Rao: A Memory (2020) is composed of a voice recording by Rao's contemporary Ashoke Chatterjee and a slideshow of photographs by Sunil Janah taken from Dances of the Golden Hall.

Published by Chatterjee and Sunil Janah in 1979, the book, named after a temple in which Shiva dances as the world comes into being, compiles images of Rao performing classical Indian dance—Martha Graham cited it as the influence behind the 1982 production Golden Hall.

The invocation of figures like Choi and Rao recalls the subtitle for Hyunjin Kim's curatorial essay, 'From Ghosts of Modernity to Spirits of the Ungovernable', with Erika Tan's two-channel video installation The 'Forgotten' Weaver (2017–2019) summoning the ground within the spectrum by recovering an overlooked history and reflecting on the implications of that recovery now.

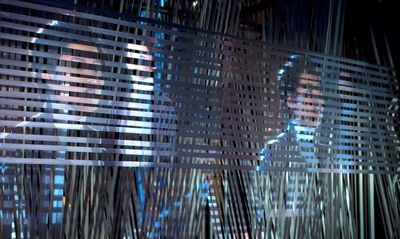

Projected onto a metal frame holding woven straps is APA JIKA, The Mis-Placed Comma (2017), in which a group of women in legal dress stand in the National Gallery Singapore, formerly the colonial Supreme Court and City Hall, and debate the memory—and its instrumentalisation—of Malayan weaver Halimah Binti Abdullah.

Abdullah died from pneumonia while participating in the 1924 British Empire Exhibition in the U.K. and was buried there in an unmarked grave. In a contemporary record of the 1924 Exhibition, her death appears in a footnote.

Tan connects this oversight to the historical exhibition that launched the National Gallery Singapore in 2015, Siapa Nama Kamu?—'What is your name?' in Malay—Art in Singapore Since the 19th Century, which included no Malay women artists but displayed an abundance of Malay women in paintings.

'Where are you my sisters?' asks the voice that narrates APA JIKA's opening frames. 'The story is incomplete. The journey still unfolds. The archive strains to incorporate'. It is this strain that Frequencies of Tradition seeks to ease by interpreting tradition beyond the archive as something palpably present and elastic: at once haunting, alive, unruly, and progressive.—[O]