Ruth Asawa: Citizen of the Universe

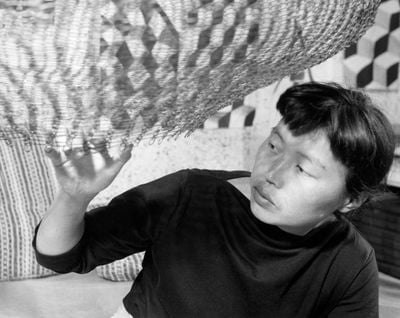

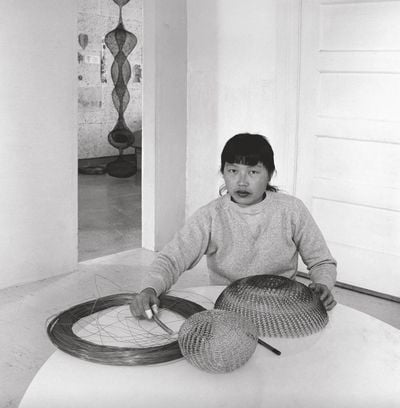

Imogen Cunningham, Ruth Asawa 6 (1957). © 2022 Imogen Cunningham Trust. Artwork © 2021 Ruth Asawa Lanier, Inc./ ARS, NY and DACS, London. Courtesy David Zwirner.

With an unorthodox and experimental education and lifelong practice devoted to integrating art, education, community, and family, the Japanese-American artist Ruth Asawa left a legacy shaped by an 'inclusive and revolutionary vision of art's role in society', writes curator Emma Ridgway.1

Alongside Vibece Salthe, Ridgway is co-curator of Citizen of the Universe at Modern Art Oxford (28 May–21 August 2022), the first exhibition dedicated to Asawa in a public institution outside of North America, organised in partnership with Stavanger Art Museum, Norway, where it will head from 1 October 2022 to 22 January 2023.

Made predominantly between 1947 and 1990, artworks in the show feature Asawa's signature looped and tied hanging wire sculptures, as well as a collection of prints, drawings, letters, and photographs that commemorate the artist's holistic approach to art and life.

Born in 1926 into a Japanese immigrant farming family in Norwalk, Southern California, Asawa worked on rented farmland with her family between classes, until 1942, when they, alongside 120,000 other Japanese Americans, were detained in internment camps during World War II.

Fortuitously, Asawa was able to study drawing with Walt Disney animators who were interned in the Santa Anita camp with them. When she and her family were moved to a relocation centre in Arkansas, she continued her creative development, resulting in a Quaker scholarship to study at Milwaukee State Teachers College in 1943.

Due to anti-Japanese prejudice, Asawa was not allowed to undertake teaching practice despite excelling, and was refused her degree. Propitiously, while studying craft in Mexico the summer of 1945, Asawa's teacher, Cuban designer Clara Porset, recommended that she consider studying with their former instructor, Josef Albers.

Urged on by another artist friend, she departed for the experimental Black Mountain College, known as BMC, in North Carolina in 1946, where the Bauhaus émigrés and artists Anni and Josef Albers taught alongside other influential artists, many of whom had also fled war-torn countries. Among them, architect and Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius, stage designer Alexander 'Xanti' Schawinsky, and dancer Elsa Kahl.

BMC was not a traditional educational establishment, as John R. Blakinger writes in the exhibition catalogue; rather, it was defined by 'a radical egalitarianism that combined progressive education and rugged American individualism with avant-garde experimentalism'.2

Asawa remained at BMC until 1949, studying with seminal cultural practitioners—painter Ilya Bolotowsky, mathematician Max Dehn, composer and theorist John Cage, dancer and choreographer Merce Cunningham, and architect, designer, and philosopher Buckminster Fuller.

Asawa would later say that at BMC, she found a place with 'no separation between studying, performing the daily chores of living, and creating one's own work', which radically changed her life.3

She was particularly influenced by Albers' courses in drawing, painting, and design, which challenged her to push the boundaries of her artistic practice through design exercises using colour, line, and structure.

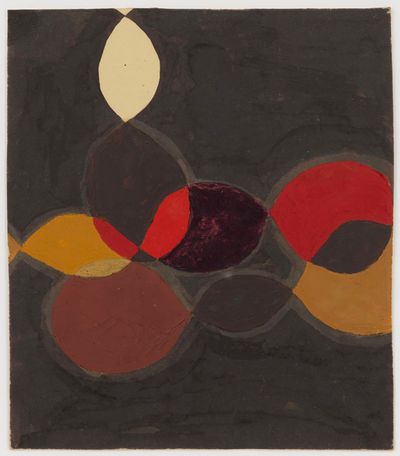

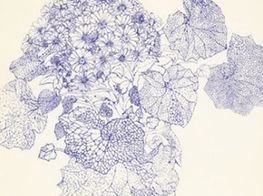

Also key to Asawa's studies was the imaginative use of simple materials like the shape of a dogwood leaf, plentiful at BMC, with which Asawa experimented creating overlapping forms and shapes, and colour studies.

As Asawa's formal experimentation progressed, so did the artist's approach to art and life, education and learning, with concepts of unity influencing her personal experiences.

In the painting Untitled (BMC.83, Dogwood Leaves) (1946–1949), for instance, the shapes are formed from experiments with bending and overlapping leaves. Folding a leaf on itself will reveal two different shades, but Asawa pushes the colour studies further, juxtaposing different hues to vibrate against each other.

While studying dance with Merce Cunningham, Asawa created pictorial studies of bodies moving through space and the choreography of their repetitive and overlapping movements.

She adeptly abstracted human forms into biomorphic, double-lobed forms in the painting Untitled (BMC.56, Dancers) (1948–1949)—two-dimensional studies Asawa would later transform into the third dimension with her wire sculptures.

A turning point came in 1947 when Asawa volunteered in Toluca, Mexico as a summer art teacher, where a local craftsman taught her the crochet loop used to make the metal wire egg baskets that had captured her imagination.

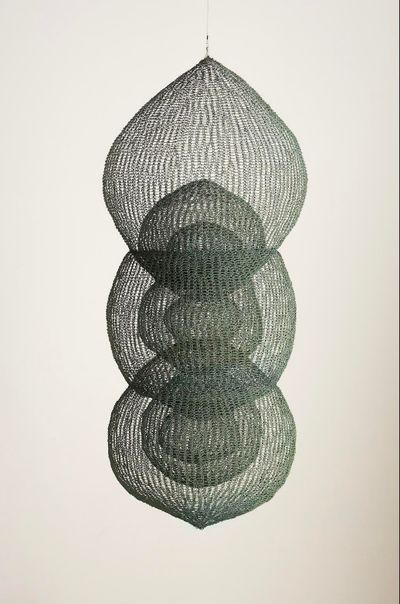

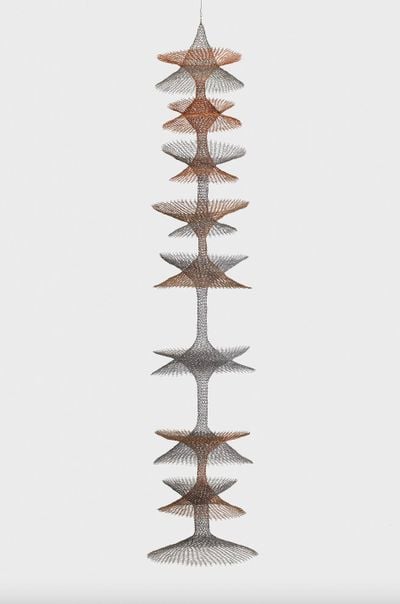

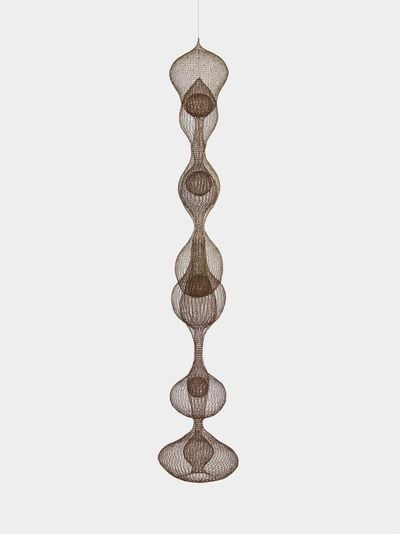

Asawa would develop this craft-based technique over decades to form her signature sculptural works. Beginning with open basket forms, they evolved into hanging, multi-lobed sculptures with forms nested within forms, made using the original looped-wire method learned from the Toluca craftsman.

Later looped-wire sculptures include Untitled (S.065, Hanging Seven-Lobed, Multi-Layered Continuous Form within a Form with Spheres in the Second, Third, Fourth, and Sixth Lobes) (1960–1963), formed with oxidised copper and brass wire.

Made using the continuous forms-within-forms construction that Asawa began developing in the early 1950s, the piece is composed of a series of overlapping spherical layers graduating from interior to exterior as a continuous surface.

Another work, Untitled (S.208, Hanging Three Interlocked, Three-Layered Spheres) (1959–1960), made of oxidised copper wire, is an example of some of Asawa's most complicated interlocking constructions, in which forms seem to continuously grow out from within themselves.

From the mid-to-late 1950s, Asawa's interlocking technique progressed to allow two forms to interpenetrate and pass through each other—a high point in her experiments in looped wire, as Tamara H. Schenkenberg writes in Ruth Asawa: Life's Work (2019).4

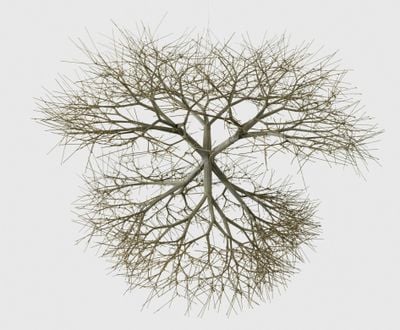

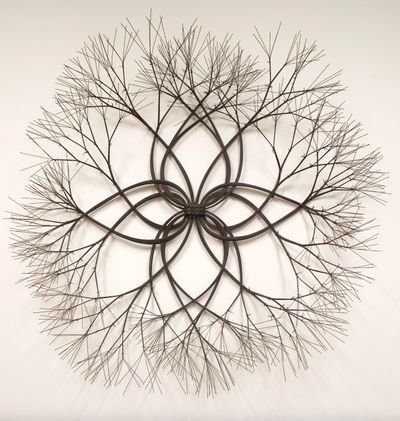

The impetus for Asawa's later signature tied-wire sculptures, developed in the 1960s, apparently came from the artist's desire to draw the skeleton of a desert plant and understand its tangled patterns, which she reproduced with wire.

With Untitled (S.052, Hanging Tied-Wire, Double-Sided, Center-Tied, Multi-Branched Form Based on Nature) (1965), Asawa took a bundle of wire tied in the centre and experimented with branching the wires in opposing directions, inspired by trees and root systems.

This natural process of emulation and repetition remained central to Asawa's learning and practice; patterns of a repeated simple action or shape are found in most of her works.

But while Asawa's work was recognised early in her career in New York, with exhibitions at the Peridot Gallery (1954, 1956, 1958), followed by the Whitney Museum of American Art (1955, 1958), and the Museum of Modern Art (1959), the tepid critical response Asawa received was likely due to gender and racial prejudices at the time.

Unthwarted, Asawa wrote to her fiancé Albert Lanier in 1948 from BMC, expressing her determination to transcend the racial and gender inequalities suffered earlier in her life. 'I no longer identify myself as a Japanese or American,' Asawa wrote, declaring herself a 'citizen of the universe'.

Having already surmounted overwhelming barriers rooted in institutionalised racial, gender, and class prejudices, she penned: 'I no longer want to nurse such wounds; I now want to wrap fingers cut by aluminium shavings, and hands scratched by wire. Only these two things produce tolerable pains.'5

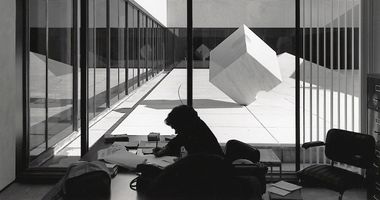

Lanier, an architecture student whom she met at BMC, had moved to San Francisco, which had passed laws in 1948 allowing interracial marriage—one of the first American states to do so. They married and settled there in 1949, eventually raising six children.

As Asawa's formal experimentation progressed, so did the artist's approach to art and life, education and learning. Art was a central part of life; she made her works at home, where she taught her children art and how to prepare the looped wire for her sculptures, and hanging her works throughout their shared, domestic space.

Hugely invested in her community and the arts education of children, Asawa co-founded the Alvarado School Arts Workshop in 1968 with friend and fellow parent, architectural historian Sally B. Woodbridge.

The experimental summer school was held in the cafeteria of the elementary school her children attended, devoid of an art curriculum at the time. There, Asawa and Woodbridge volunteered to teach weaving and papier-mâché sculpture, made using simple, everyday materials.

Eventually, the Workshop expanded to include 50 San Francisco public schools employing artists, musicians, and gardeners, and in 1982, Asawa founded the first public arts school in the city. In 2010, that school was renamed Ruth Asawa San Francisco School of the Arts to honour her seminal work in education.

In tandem, Asawa received many public commissions in San Francisco, among them two origami fountains at the Nihonmachi Pedestrian Mall in Japantown, from 1975 to 1976 and 1999. Their forms are based on paper-folding experiments at BMC, as well as childhood experiences with origami.

While Asawa's work was gradually taken more seriously in her lifetime, the recognition for her contributions to art history continues to grow exponentially. In 2020, the U.S. Postal Service honoured the artist with a series of ten stamp designs featuring her signature wire sculptures, and in 2022, the artist was featured prominently in the 59th Venice Biennale's central show The Milk of Dreams—all reflecting Asawa's amplifying importance as an artist.

Citizen of the Universe at Modern Art Oxford is but another step in expanding Asawa's reach, giving audiences a chance to see for themselves how Asawa challenged and redefined the conception of sculpture at a time when the medium was rigidly defined. —[O]

1 Emma Ridgway, 'Introduction', exhibition catalogue for Ruth Asawa: Citizen of the Universe, ed. Emma Ridgway and Vibece Salthe (2022): p.9.

2 John R. Blakinger, 'Camouflaging Asawa', exhibition catalogue for Ruth Asawa: Citizen of the Universe, ed. Emma Ridgway and Vibece Salthe (2022): p.70.

3 Ruth Asawa, 'Artist's Statement', exhibition brochure for Ruth Asawa: Completing the Circle, Linhares (2002). Cited in exhibition catalogue for Ruth Asawa: Citizen of the Universe (2022): p.120.

4 Tamara H. Schenkenberg, Ruth Asawa Life's Work, (Pulitzer Arts Foundation: St Louis, in association with Yale University Press: New Haven and London, 2019): p.140.

5 Ruth Asawa, 'Letter to Albert Lanier', postmark 29 December 1948, The Sculpture of Ruth Asawa: Contours in the Air, (Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco in association with University of California Press: Oakland, 2006): p.51. Cited in Emma Ridgway, 'Ruth Asawa: Citizen of the Universe', exhibition catalogue for Ruth Asawa: Citizen of the Universe, ed. Emma Ridgway and Vibece Salthe (2022): F.2, p.19.

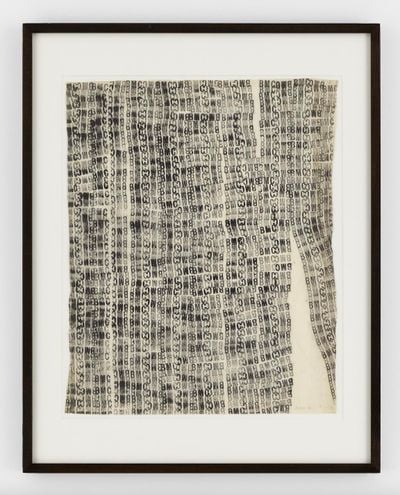

![Untitled (P.002-I Tied-Wire Sculpture Drawing with Five-Pointed Center Star, Embossed [Silver]) by Ruth Asawa contemporary artwork works on paper, mixed media](https://files.ocula.com/anzax/29/29b0c3ad-9578-4ea3-88ff-e1555af2202a_200_201.jpg)