Another Revolutionary Woman: Ghada Amer’s Paravent Girls

When looking at the works of New York-based artist Ghada Amer, medium-specific ways of thinking about painting and sculpture fall short of capturing the intricacies of her multifaceted approach.

Exhibition view: Ghada Amer, Paravent Girls, Tina Kim Gallery, New York (26 October–9 December 2023). Courtesy Tina Kim Gallery. Photo: Hyunjung Rhee.

Amer has a longstanding method of appropriating images of women from porn magazines, presenting them in ceramics, embroidered paintings, and later bronzes. The 'Paravent Girls' debuted in Marseille last year in a multi-venue survey with Mucem.

For her solo show Paravent Girls (26 October–9 December 2023) at Tina Kim Gallery, New York, she introduces subtle yet compelling interplays between the two- and three-dimensional. Deploying folding screens as architectural interventions, Amer combines the concept of paravents (windscreens) with stylised portraits of women to create a rich, embodied space for female subjectivity.

The first space gives glimpses of Amer's processes for representing women in porn across different materials and surfaces. While portraiture often generates a sense of relational intimacy by placing a viewer in close proximity with a subject, Amer's portraits of porn models draw attention to the male gaze that drives mass consumption of women's bodies. More importantly, however, is how the women gaze back, gaze at each other, or avert external gazes.

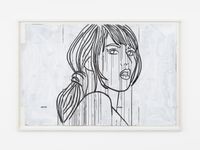

Study for Jennifer and Barbara (2021) is an outsized portrait of a young woman with a pouty, half-open mouth. It is painted with black ink on cardboard covered with white acrylic paint, with drips of excess ink running down the image.

This portrait is rendered in sculptural relief in The Red Portrait (bronze) (2021), where a similar image on cardboard is cast in bronze using a lost-wax process. Against the painted white background, dark, densely populated lines are raised in three-dimensional relief to form the outline of a young woman's head.

Diagonally across stands the towering Sculpture with Wounds (bronze) (2023) at over two metres tall, which depicts the bust of a nude woman with a direct, confronting gaze. The rich patina and texture of the bronze faithfully transfer the organic imprints of the artist's hands that have shaped the grooves of the figure's outlines.

Despite the variances in Amer's play with scale, material, and texture, these works are united in their stylistic renderings with simplified outlines that recall Pop art. Whether defining visages or recreating the drip effects of ink and paint, Amer's distinctive lines are seen to grow, sweat, and melt over each other.

In contrast, the second space showcases three monumental, bronze folding screen sculptures—collectively titled 'Paravent Girls'—in architectural cadence. As privacy devices, paravents are often used to delineate subject and object, viewer and the viewed. Amer depicts figures on both sides of the sculpture, forcing the viewer into motion—an act that disrupts the passivity of the hetero-patriarchal gaze. Here, power dynamics are far from fixed.

Amer transforms her characteristic materials and subjects—discarded cardboard and women in pornographic images—into the monumental. It is remarkable how her work stands in contrast to Richard Serra's Reverse Curve (2005/2019), a gigantic, winding steel sculpture steeped in masculine, Minimalist traditions. Amer's version of a curving, monumental metal sculpture is characterised by such details as the impression of corrugated cardboard on the bronze; the play between light and shadow created by cardboard flaps; and ambivalent glances thrown by the girls.

There is the oft-cited incident that Amer—who was born in Cairo and educated in France—was rejected a place at a French art school on account of her gender. In an interview with The New York Times, Amer described how much of her boundary-pushing experimentation with painting and sculpture is fuelled by her anger at gender discrimination. 'But I'm a woman, as well—who makes art about women. It's frustrating,' she said.1

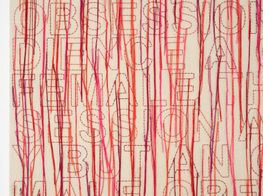

The manifestation of these frustrations can be seen in Another Revolutionary Woman (2022). The work juxtaposes the flirty glance of a woman with repeating lines of embroidered Arabic text. Quoting Egyptian writer and psychiatrist Nawal El Saadawi, it reads: 'The Revolutionary man will be considered a popular and respected hero but the revolutionary woman will be considered weird and abnormal and unfeminine.'

Continuing Saadawi's advocacy for women's right to sexual pleasure, Amer depicts women in alternating states of seduction, self-pleasure, or daydream. The consistency of her subjects is itself a political act. The artist shows that monumentality and softness can co-exist as two sides of the same coin.

Paravent Girls is capped by a moment of heightened erotic tension. At the far end of the gallery, Suzy Playing (bronze) (2021) portrays two women locked in a tender embrace, their gazes soft and brassieres exposed. The image may be based on pornographic sources, but with Amer's intervention this moment of intimacy is frozen, reframed, and rendered forever monumental.

Bathed in a protective aura, they invite an active gesture of looking, as opposed to passive consumption. A paravent is something that guards against the wind. Amer's paravent girls, whether crying in joy or melting in ecstasy, shield themselves from erasure and violence, and the price of being a revolutionary. —[O]