Juan Ford: Artist of Seduction

At Galerie du Monde, Hong Kong, the centrepiece of Juan Ford's recent solo exhibition Blank (15 March–20 April 2019) was Recollector (2018), a hyper-realistic portrait of a solo female figure standing against a clear blue sky, the painting cropped at her knee. She is costumed in white drapery, although fragments of red, blue, and yellow under her arms and peeking through at her knee suggest a further ensemble underneath. Ford often paints from photographs he takes of friends, himself, or mannequins dressed in fabric, tape, and other man-made and natural detritus. In this instance, Ford used a mannequin; however, this is impossible to tell, with the figure's arms sheathed in cloth down to her fingers, her face similarly wrapped, and an oversized pair of sunglasses covering her eyes. Shrouded and head turned slightly, she looks practically human, though her costume and the manner in which she stares beyond the viewer suggests she is looking to a world other than our own.

Juan Ford, Recollector (2018) (detail). Oil on linen. 180 x 150 cm. 70 7/8 x 59 1/16 inches. Courtesy Galerie Du Monde.

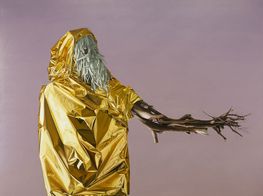

While Recollector was not the first work Ford created for the show, it is the work the show came to revolve around. The painting's centrality was reflected in its size—at 1.8 metres tall (in proportion with the viewer), it was the largest artwork gracing Blank. Present in the exhibition were two other portraits of similarly bespectacled figures wearing layered costumes. The Mystic (2019) depicts a frontal bust and Naiad (2019), named after the water nymphs of Greek mythology, shows a figure dressed similarly to Recollector but visible only from the waist up. Each of the figures are dressed in costumes sticky with white paint—the result of an experiment in which Ford randomly decided to pour a full bucket of white paint over his sculptural creations to suddenly find in his figures 'an Athenian statue or a muse of ancient times'.

Early on in his career, the Australian-born Ford demonstrated an interest in the theories of classical antiquity. In 2006, when he was awarded the Australia Council for the Arts Studio Residency at The British School at Rome, he began a series of paintings of marble busts, including Husk #6, which depicts a dramatically lit bust floating against a dark background. The artist acknowledges the influence antiquity has had on his practice, in particular the ancient Greek understanding of light as being composed of two distinct strands, lux and lumen—lux being the light of rational, scientific enquiry, and lumen being the light of the imagination. The bright blue sky behind the objects and figures in the artist's paintings is a reference to his interest in these ideas of light. However, it is equally a reference to the harsh, dry light that permeates the Australian landscape.

Around the same time that Ford started making references to antiquity in his work, he also started to introduce Australian fauna. Older paintings, like the ominously titled The Last Enemy (2007) shows the underside of the human skull with leaves sprouting from its foramen magnum, while One Last Embrace (2008) is a painting of white tape wrapped around Australian bottlebrushes, foreshadowing the intertwining of the human figure with twigs and animals in Recollector. Over time, plants have come to adopt anthropomorphic forms in his paintings. Guardian (2018)—another painting in Blank—depicts a human bust with a horned helmet made out of leaves and has its precedent in the T-shirt-wearing branches in the earlier artwork Osaka Speed (2013). In Degenerator (2013), a bespectacled figure holds a rifle fashioned out of tree branches held together by tape. Thick green paint oozes from beneath his sunglasses and mouth, dripping onto his white shirt, implying that his body might be full of the artificial substance. With her oversized eyewear and veil to fend off the elements, the figure in Recollector could be a similar fighter.

Ford's works are intended to clearly reference his home country, but should not be limited to a discussion of it. While the artist has stated that he doesn't want to impose readings of his work upon viewers, he acknowledges that he does wish the work to convey an environmental message (the artist himself is a vegetarian for environmental reasons). A painting in Blank entitled El Lissitzky (an artist who advocated for artists as 'agents of change') perhaps references the responsibility Ford feels in using his work as a subversive tactic of environmental activism.

Ford describes a desire for his artwork to act as a 'circuit breaker'. Certainly, his paintings are unashamedly an amalgam of subject matter, referencing multiples genres and a diversity of cultural connotations, and resisting any single, straightforward interpretation. An avid reader of history, he notes the traditional art-historical approach is linear and often emanates from the perspective of those in power. As an art student in the 1990s he learnt a version of art history very much founded on a Western art history canon, from the Greeks through to the New York School and the version of Modernism espoused by Clement Greenberg and Robert Hughes. However, Gerhard Richter was an important early influence in demonstrating to Ford that there were other possibilities for art: 'it was as if Richter had taken a bulldozer through the myth of what art 'should be', and laid down alternative paths to trample, short-circuiting the rigid trajectory of Modernism.' The lone figure in Recollector may summon to mind ancient Greco-Roman statuary, religious sculptures of the Madonna, or a post-apocalyptic warrior figure from the film Mad Max, but it might equally evoke a shaman. And while portraiture has long prevailed in Ford's practice—the artist has been nominated four times for the Archibald Prize, Australia's foremost portraiture accolade—the artist's output references landscape painting as much as it does a history of botanical drawings. Ford collapses the different mediums and genres, creating his own artistic vocabulary where his paintings are the outcome of a sculptural and photographic process. His portraits are not merely depictions of humans, but also of trees, flowers, foliage, landscape, culture, history, and light.

Ford's work is painstakingly completed to hyper-realistic perfection. However, the result is not a bland simulacrum of the creations that Ford photographs. The artist has explained his focus on the human figure as a way to stage an inner vision, 'something that has come from play, from dreams, from thoughts'. The paintings are bolstered by layers of meaning, some obvious and some less so. In the catalogue accompanying Blank, writer and curator Andrew Gaynor notes that the artist's Masters by Research, undertaken at RMIT University in 2000, examined the combined use of painted realism and anamorphosis—a technique famously used by Hans Holbein in his painting The Ambassadors (1533), and in the woodcuts of the German artist Erhard Schon (c 1491–1542), who would use this distorting technique to disguise alternative meanings to his work. So perfectly rendered as to seem to be a photograph, Recollector draws the viewer in by its seeming celebration of reality; however, the figure is born of paint and imagination, and upon closer consideration we see her as something otherworldly, her strange clothing drenched in paint and adorned with plastic creatures and twigs. Ford seduces the viewer with his technical virtuosity, but he equally surprises us with what we find, daring us to imagine, perhaps leading us to conjure up the world into which Recollector stares.—[O]