Mona Asks, What’s in a Namedrop?

The value of fame comes up for appraisal at the world's edgiest art museum. Wu-Tang Clan, Pablo Picasso, William Shakespeare, Margaret Thatcher, and Holden Torana are just a few of the big names in an exhibition that's both fascinating and, perhaps knowingly, fatiguing.

Darren Sylvester, Filet-O-Fish (2017), Courtisane endormie (Sleeping courtesan) (1920), and Holden Torana (LX) SLR 5000 A9X Sedan (a hotted-up Torana) (1977). Exhibition view: Namedropping, Mona, Hobart (15 June 2024–21 April 2025). Courtesy the Museum of Old and New Art, Hobart, Tasmania, Australia. Photo: Mona/Jesse Hunniford.

In an increasingly attention-based economy, a bigger name is better in so many ways. Brand equity is assigned real dollar values. Clout furnishes opportunities. For audiences and consumers, recognition is a proxy for quality. 'Never heard of them' is damning. Yet Mona is, to me, more compelling than MoMA. I'm less famous than Martin Shkreli, hiker of pharmaceutical prices and big Wu-Tang Clan fan, but I'm also less hated.

The slippery value of brands and celebrities—both famous and infamous—is the subject of Namedropping (15 June 2024–21 April 2025), this year's major exhibition opening at the Museum of Old and New Art (Mona) in Hobart, Tasmania. The presentation of some 200 objects spans modern and contemporary art, indigenous artefacts, pop-culture memorabilia, and one 'hotted-up Torana', a term Mona's founder, David Walsh, has also used to describe the museum.

The 1977 Holden Torana (LX) SLR 5000 A9X sedan is one of the first things you encounter in Namedropping. It's a sexy car, and sex is at the centre of this exhibition. Walsh subscribes to the hypothesises that we seek status primarily to attract mates, and sharing the things we like helps us find people we like.

'This thing we call "taste" saves such a lot of time and effort,' he writes in exhibition text accessed via the museum's suggestively named app, The O. 'And that's biologically useful.'

The museum claims the car 'makes the point about namedropping and status better than most of the art in this exhibition.'

Leaning too hard on evolutionary psychology can lead to impoverished explanations of human behaviour, which is influenced by much more than evolved traits. Thankfully, there's significantly more to this exhibition than this one 'point'.

The Torana is displayed in a gallery-turned-garage with a concrete floor and exposed wooden plank walls. It's decorated like a true blue Aussie man cave—another term Walsh uses to describe Mona—with a poker table and a dart board, a Gray-Nicolls cricket bat signed by players in the '83–'84 Tri-Series, trophies, beer bottles, and a Supergirl nude calendar opened to May / June 2008.

There's also gold and platinum David Bowie records, signed photos of Marilyn Monroe and the cast of Casablanca (1942), letters by Charles Darwin, Gustave Flaubert, and Victor Hugo, signatures by Charles Dickens (scratchy) and Louis Armstrong (virtuosic), a painting erroneously attributed to Vincent van Gogh, and an enigma machine used to encrypt Nazi communications, among many other items. It's a blitzkrieg of unrelated history, and this is just the first of a dozen galleries in the show.

Of course, you don't have to look at everything. Mona offers a choose-your-own-adventure approach to exhibition design. There's no wall text introducing the show as a whole, different sections, or individual works. When an item catches your eye, you can usually access two or three different kinds of information on The O, categorised under the headings: 'summary' (basic info), 'ideas' (quotes), 'art wank' (more traditional exhibition texts), or 'gonzo' (anecdotes). The main threads of the exhibition are left to the viewer to devise from the prominence, proximity, and number of works that touch on a given theme.

After the Torana, the most conspicuous items in the man cave are four framed front pages of The West Australian and a fibreglass tuna—all works by Melbourne-based artist Danius Kesminas. The newspapers relate the story of Australian writer Robert Hughes (1938–2012), described by The New York Times in 1997 as 'the most famous art critic in the world', who was charged with dangerous driving after crashing his car on a fishing trip in 1999. Kesminas tracked down Hughes' rented Nissan Pulsar at a scrapyard, where it had already been cubed. That work, titled Post-Traumatic Origami (1999–2002) is displayed in the next room of the exhibition on an illuminated plinth. Asked about the work soon after it was first shown, Hughes told The New York Times, 'I don't want to see it. In a sense, I was it.'

Kesminas' strategy of making art from a famous figure's life is the conceptual equivalent of using precious stones and metals to make jewellery. The wrecked car, previously called Hughbris, is freighted with meaning. It's a portrait of a complicated figure, a self-described elitist who recklessly called victims of his car crash 'low-lifes' and told one reporter, after emigrating to the United States, that Australia could be towed out to sea and sunk.

Aotearoa New Zealand artist Simon Denny achieves something similar with Power Vest 6 (2020), a Patagonia-style down vest in peacock blues and greens embroidered with the logo of San Francisco tech company Salesforce. The vest was made with silk scarves previously owned by Margaret Thatcher, the British Prime Minister whose neoliberal policies helped sever the haves from the have-nots, a trend that has only worsened in the tech era. It's not just Thatcher's name but also those of the brands he references that Denny uses to instil meaning in his work. Patagonia and Salesforce are just two of the many brands artists engage with in the exhibition.

Displayed on a pink rug near Denny's vest and Kesminas' cubed car, for instance, is Melbourne-based artist Darren Sylvester's Filet-O-Fish (2017). The work is a designer sofa screen-printed with a discontinued wrapper design for McDonald's best burger. That the chaise longue is also associated with therapy suggests a relationship between comfort food and existential dread. Emma Bugg's Big Mac Brooch (2016), displayed in the last hall of the exhibition, is made from an unpreserved Big Mac purchased in 2015, which shows no visible signs of decay, suggesting we may be nearer oblivion than the burger is.

One of the largest works in Namedropping is Chinese artist He Xiangyu's flaccid Italian leather tank, Tank Project (2011–2013), a life-sized copy of a T-34 made from 250 cowhides. Over four months, the artist and his team snuck into an army base on the border with North Korea to take exact measurements for the piece, which was then cut and stitched together over two years by workers usually hired to churn out fake handbags. Emblematic of China's embrace of brands and capitalism after Mao Zedong—a political softening—the work is displayed in a room with IP-ambivalent brown wallpaper that combines the logos of Louis Vuitton and Mona. It's one of several galleries where visitors can make like a Sackler and purchase naming rights, with the winners' chosen text displayed on digital screens until someone else pays more.

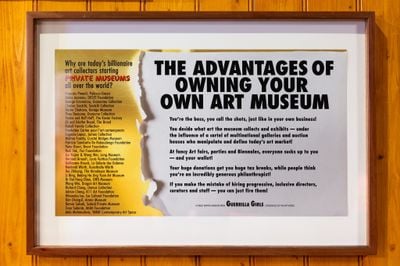

A work by Australian artist Steven Rhall, who says he operates from a 'First Nations, white-passing, genderqueer, positionality', suggests it's not just corporations and individuals that have brands, but also groups with shared identities. Ideas of First Nation art practice (2024) is a parody of an ambulance-chasing lawyer's ad. Rhall's billboard—big enough to be seen by traffic on the side of a highway—yells, 'ABORIGINAL ART? "Better Call Rhall!"'

The work faces the jetty where many visitors first arrive at the museum on camouflaged catamarans with fibreglass-sheep seats. It thus functions as a twisted 'acknowledgement of Country', the practice—widespread in Australia—of noting the Indigenous owners of a territory in entrance halls and on website landing pages.

Indigenous identities may be commodified in today's contemporary art world, but an audaciously literal audit by Spanish artist Santiago Sierra testifies to the enduring market value of whiteness.

ECONOMICAL STUDY ON THE SKIN OF CARACANS (2006), exhibited in the same room as He's tank, features 30 black and white photographs of people's backs shot in the city of Venezuela. Ten subjects had no money to their name, 10 had U.S. $1,000, and 10 had $1,000,000. Merging the pixels of each group produced different shades of grey, from which the artist calculated the monetary value of black and white. Black was worth negative $2,106 while white was worth $11,548,415.

Mona's inclusion of a work by Sierra says a lot about the museum. People were outraged in 2021 when the institution requested the blood of first nations people, which Sierra planned to use to soak a Union Jack as part of the affiliated Dark Mofo festival. Senior writer Luke Hortle draws attention to the incident on The O, describing it as 'an open wound for us at Mona'. There's something to admire in publicly airing that wound, even if the injury amounts to stepping on a rake.

Namedropping selectively embraces the notion that there's no such thing as bad publicity. The exhibition includes a bronze Hello Kitty (2001) sculpture by Tom Sachs and a hyperreal painting of designer Robert Israel, Bob (1970), by Chuck Close—both of whom have been publicly accused of sexual harassment. Curiously, the exhibition doesn't acknowledge that stain on their names, but it does reserve another gallery for bad guys.

This blackened room features works including: a tin floor sculpture by American minimalist Carl Andre, who was accused of murdering his wife Ana Mendieta; a murky painting by Scottish-born Australian painter Ian Fairweather, who wrote of his 'boy' in Manila, 'I think it better to love even pervertedly than emptiness'; and a brightly coloured painting by ultra-violent Australian gangster Mark 'Chopper' Read.

Despite lopping off his enemies' toes with bolt cutters and killing, in his estimation, four to seven people, Read sold nearly all of the 27 paintings in his 2003 debut exhibition at Dante's Upstairs Gallery in just two days. His books have sold more than 500,000 copies, his life was made into a movie starring Eric Bana, and he lent his name to products including peanuts, wine, and beer.

Hybristophilia, also known as Bonnie and Clyde syndrome, is the name given to sexual interest in criminals, including serial killers. That Ted Bundy, Charles Manson, and even Jeffrey Dahmer, who was gay, received letters from multiple female suitors while in prison illustrates how maladaptive celebrity worship can be.

More surprising, perhaps, is how frustrating and disappointing it can be to collect or encounter objects touched by celebrity.

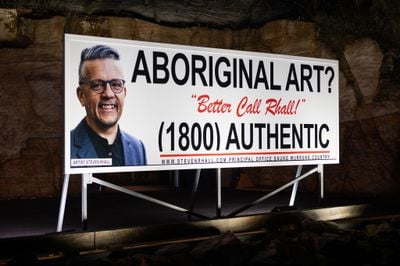

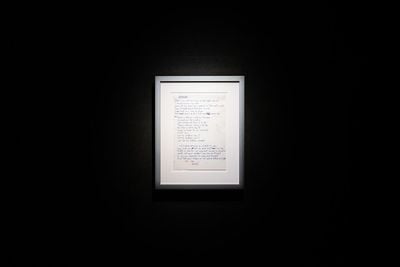

The lyrics from Bowie's 'Starman' (1972) appear in the final room of the exhibition, along with a number of other items, including the Big Mac, the Ancient Egyptian coffin of Ankh-pefy-hery, and a fabulous Mercedes Benz-shaped casket made by Ghanaian craftsman Paa Joe in 2010. Written in blue ink on a sheet of gridded paper, the lyrics have the tidy penmanship of a teacher's pet. Depressingly, the words 'Bowie Lyrics' have been added in pencil. There's no great aura, or soul, or inspiration, or experimentation to be sensed here because these are not the original scratchings of an artist at work but words Bowie dutifully transcribed for the album's record sleeve.

That Walsh paid around U.S. $210,000 plus fees—$70,000 over the ceiling he'd given his bidder—for a song he concedes isn't one of his favourites only makes them sadder. Advised by conservators against displaying the lyrics for the duration of the show, so they could continue to be seen for the next 70–600 years, Walsh pushed back. He argued the lyrics were really only relevant to a cohort of living fans, and said, in The O, 'if we preserve it, we would be preserving it for a posterity to which it would be irrelevant.' So much for artistic immortality.

Also part of the show is Shakespeare's 'First Folio' and, while it's neat to see the oversized page numbers and the quaint full stops after the titles of the plays, neither it nor the 234 other extant copies, published seven years after his death, bring you any closer to the Bard himself.

Walsh's wife, Kirsha Kaechele, who established the museum's evidently illegal Ladies Lounge, offers a similarly melancholy note on a cabinet of ceramics by Pablo Picasso, another candidate for the bad guys gallery. These are displayed down a dark hall with the sole copy of Wu-Tang Clan's Once Upon a Time in Shaolin (2014), once owned by Martin Shkreli, which is presented in an ornate silver briefcase with a leatherbound book. What does it sound like? I defer to Australian rapper Briggs, who told the BBC, 'It's a very cinematic record. The production was cool. Great verses.'

Kaechele purchased the Picassos from Sotheby's online, and they arrived bigger and smaller than she thought: some were originals, others editions. One was the wrong piece entirely, a misclick. She says she's not yet proud of the museum's collection of Picasso ceramics, which really is quite wonderful, describing it in The O as 'the victim of auction roulette and a deranged online curator'.

There's a fine line between being self-aware and self-obsessed but, for the most part, Mona's willingness to share moments of messiness—a sometimes clumsy grasping at transcendence—is refreshing. It doesn't pretend to be right, or aspire, much less ambitiously, to political correctness. For better and for worse, it's personal.

Walsh made his millions as part of a gambling syndicate called the Bank Roll, a tale laid out in Richard Flanagan's 2013 profile for The New Yorker, which should be required reading for visitors to the museum. He has said gambling causes money to change hands, but doesn't amount to an achievement the way, say, founding an art museum does—though even that isn't a straightforward satisfaction to him.

'I'm not sure that art is so important for me,' Walsh is quoted as having said in the profile. 'It is the relentless dissecting of myself to bring me closer to an understanding of why I do what I do that seems to be important to me.'

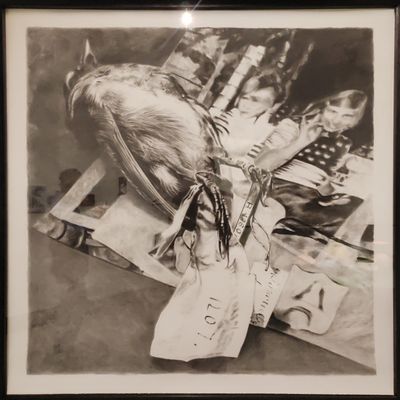

There are so many names to drop in Namedropping—I haven't mentioned Tino Sehgal, Danh Vō, Andy Warhol, and many others—but the work that seems most illuminating in this regard is none of these, nor the Torana; it's a simple graphite and charcoal drawing by Australian artist Cassandra Laing.

Darwin's Girls (2006) depicts a toe-up bird specimen Charles Darwin collected on his journey to the Galápagos islands in 1835. Beneath the bird is a photo of the artist and her sister, Amanda, who died from complications of breast cancer in 1999. In 2006, shortly before she began the drawing, Laing was diagnosed with the same disease, which also killed her grandmother.

The work is a meditation on the beauty and cruelty of evolution—genes good and bad passed down—which ushered the artist into an early grave.

Laing isn't the biggest name in Namedropping, but she receives the most heartfelt of Walsh's written contributions. It's a timeline that includes her birth, Walsh's first meeting with her in April 2007 (when he says he was 'engaged by her art and her remorseless intellectual honesty'), a plan to meet up the following year, her death in September 2007, and the date in February 2008 when she failed to show up. The last, heartbreaking entry is dated 05/06/2024: 'Cassandra continues to help make my life worth living.'

It's connection, not celebrity, that's the gambler's best hedge here—not against extinction but, more pressingly, ennui. —[O]