NGV Curator Susan van Wyk Shares Insights on 5 Photographs

This month the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV) in Melbourne opens their largest-ever survey of the photography collection with over 300 works by Australian and international artists on show, dating from the 19th century through to today.

Susan van Wyk with Candida Höfer, Teylers Museum Haarlem II (2003). Exhibition view: Photography: Real and Imagined, The Ian Potter Centre, NGV Australia, Melbourne (13 October 2023–4 February 2024). Photo: Tim Carrafa.

Photography: Real and Imagined (13 October 2023–4 February 2024) sheds light on two contrasting perspectives on the photographic medium—considering it a real-world documentary record on the one hand, or as a product of imagination and illusion on the other.

Invited by Ocula Magazine, NGV's senior curator of photography Susan van Wyk introduces five images in the exhibition, sharing insights into the photographs of Hiroshi Sugimoto, Wolfgang Sievers, Hank Willis Thomas, Helen Levitt, and Imogen Cunningham.

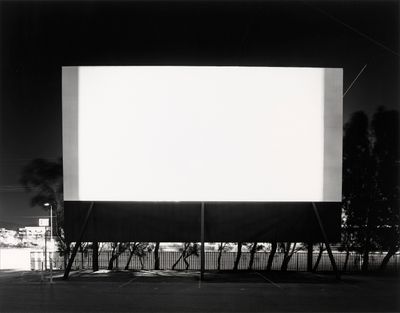

1. Hiroshi Sugimoto, Winnetka Drive-In, Paramount (1993)

Light and time are both the means and subject of Hiroshi Sugimoto's 'Drive-In Theaters' series. To produce the images, the artist directed his camera at the movie screen, or in the case of Winnetka Drive-In, Paramount (1993), the screen at a suburban drive-in theatre. When the film started, Sugimoto would open the lens shutter of his large-format camera, closing it the moment the movie ended.

In a 2016 interview [with Alejandra de Argos] the artist described the images in this series as having 'accumulated the information of many millions of small photographs that a movie consists of. Before the invention of movies was the invention of photography. To make a movie, you have to sew single-shot photographic images together ... It is all an illusion to the human eye.'

The resulting photograph contains a concentration of the moving images and projected light of the film into a vivid rectangle of white light. In it Sugimoto captures the magic of photography and cinema, and the nostalgia of the drive-in.

2. Wolfgang Sievers, Shift change at Kelly & Lewis engineering works, Springvale, Melbourne (1949)

After leaving Germany in 1938 in the build-up to the Second World War, Wolfgang Sievers settled in Australia, bringing a firmly held belief in the union of art and industry, and the self-declared desire to 'assist this country through my knowledge as thanks for the freedom I can enjoy here.'

Soon after arriving, he established a successful practice as a photographer and received acclaim for his architectural and industrial photography. The human face of industry is captured in Sievers' photograph of the change of shifts at the Melbourne engineering works Kelly & Lewis, where a sea of men and women are shown surging into work.

Sievers' high vantage point and sharp focus in this image is informed by his rigorous formal training at the Contempora School for Applied Arts in Berlin, where he was exposed to New Objectivity. Here in this photograph, this approach is applied to the upward-facing, smiling faces of the masses, suggestive of Sievers' belief in the importance and dignity of work.

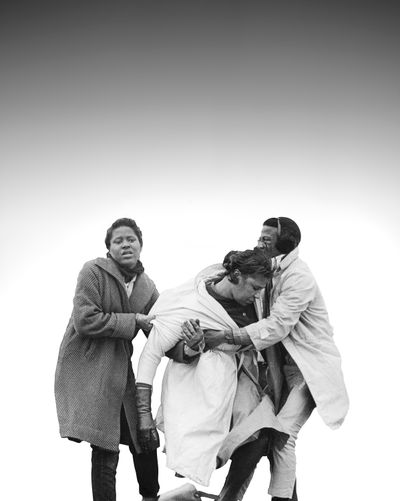

3. Hank Willis Thomas, Amelia falling (2014)

Hank Willis Thomas' photographic prints on mirrors are sometimes difficult to look at, but with the viewer's reflection integrated into the image they are also impossible to ignore. In this uncomfortable yet compelling image, Willis Thomas asks his audience 'not to be passive but to actually think about active participation'.

In Amelia falling, we bear witness to the shockingly violent incursions into what was intended as a peaceful civil rights protest march in Selma, Alabama. Willis Thomas' source image, a photograph taken in 1965 by photojournalist James 'Spider' Martin for The Birmingham News, shows civil rights activist Amelia Boynton Robinson being carried by fellow marchers after being teargassed and beaten by state troopers during the protest.

Through his use of archival images, Willis Thomas draws connections between historical moments and contemporary life, leaving little space to remain a dispassionate observer.

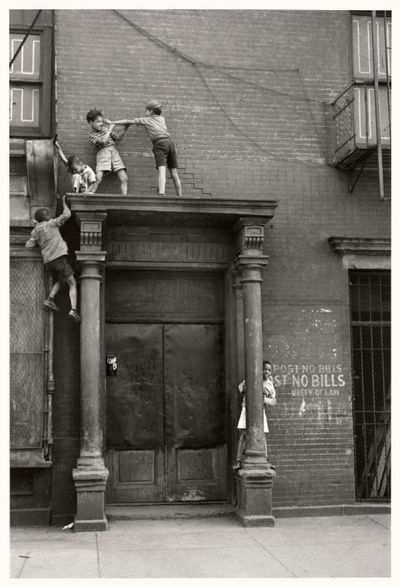

4. Helen Levitt, New York (Boys fighting on a pediment) (c. 1940)

Helen Levitt's photographs are celebrated for their depiction of everyday life in New York in the 1940s and 50s. Influenced by her connections to Henri Cartier-Bresson and Walker Evans and avant-garde photography and film from Europe and Russia, Levitt developed a style of street photography that captured the uncanny in the everyday.

Reflecting on Levitt's approach to photography, American writer James Agee noted that 'It would be mistaken to suppose that any of the best photography is come at by intellection; it is, like all art, essentially the result of an intuitive process, drawing on all that the artist is rather than on anything he thinks, far less theorises about.'

Levitt was fascinated with the behaviour and actions of children on the streets of the city, seeing surreal qualities in their play. In this image—one of her most celebrated photographs—she shows a group of young boys fighting on the street. There is a sense of danger, but also a sense that we are glimpsing a world in which adults are strangers and the usual rules do not apply.

5. Imogen Cunningham, The unmade bed (1957)

At the time she photographed The unmade bed (1957), American photographer Imogen Cunningham was in her seventies and had been exhibiting her photographs for more than 50 years. She was not only well versed on the major styles and movements in 20th-century photography, but was also an influential artist and teacher.

In 1957, while teaching at the California School of Fine Arts in San Francisco, Cunningham overheard her colleague Dorothea Lange set a task for her students to photograph an ordinary object that they used every day. Cunningham is said to have set the same task for herself. The unmade bed is an image constructed with prosaic elements including discarded hairpins and crumpled bedsheet.

Cunningham once said, 'I still feel that my interest in photography has something to do with the aesthetic, and that there should be a little beauty in everything.' In this quiet and unassuming image, Cunningham has created both an elegant still life and an unexpectedly tender portrait of a woman recently risen from sleep. —[O]