Tehching Hsieh at the 57th Venice Biennale

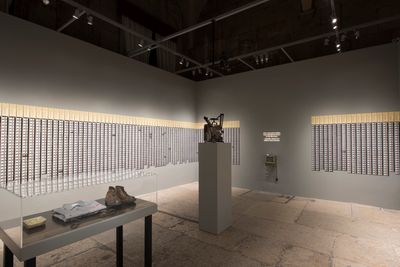

Taiwan's contribution to the 57th Venice Biennale is an exhaustive record of the passing of time—an ostensibly banal proceeding that has here been reframed in a monumental way. Staged in Palazzo delle Prigioni, Doing Time (13 May–26 November 2017) is a long overdue presentation of Taiwanese artist Tehching Hsieh's oeuvre of time-based performance art.

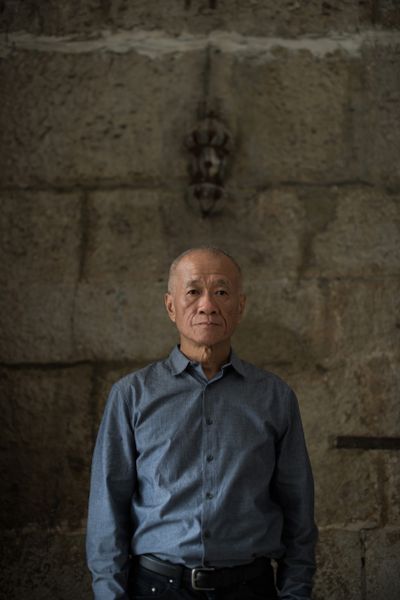

Tehching Hsieh. Photo: Hugo Glendinning.

Known for his One Year Performances or 'lifeworks' carried out in New York during the late 1970s and early 1980s, Hsieh is widely credited as a pioneer of durational aesthetics who examined the corporeal and psychological experience of time. Doing Time is curated by British writer and professor Adrian Heathfield and brings together documentation of Hsieh's lifeworks in addition to never-before-seen early pieces.

The partnership between Heathfield and Hsieh dates back several years: in 2009, after a long correspondence and collaboration, the two released a poetic monograph titled Out of Now: The Lifeworks of Tehching Hsieh, comprising extensive documentation and analysis of Hsieh's works. Following a thirteen-year period of self-imposed isolation from the art world (1986–1999), archival documents of Hsieh lifeworks have been exhibited at MoMA (2009), Guggenheim Museum (2009), Liverpool Biennial (2010), Gwangju Bienniale (2010) and in the São Paulo Biennial (2012).

As part of the Manchester International Festival 2009, the performance series 'Marina Abramović Presents' was dedicated to Hsieh. However, the presentation in Venice is the first occasion that several of the lifeworks will have been seen together in their fullest forms.

Born in 1950 in Nan-Chou, Taiwan, Hsieh dropped out of high school as a youth and took up painting and experimenting with performance art. After completing his compulsory military service in 1973, Hsieh became a sailor and in July 1974, seized the opportunity to jump ship while docked in the United States.

Disembarking in Philadelphia at 24 years old, Hsieh followed the age-old siren song for wanderers and made his way north to New York. Working minimum-wage jobs and speaking very little English, Hsieh was an outsider in the city, his illegal immigration a form of voluntary exile that committed him to a life at the fringes of society.

When Hsieh left home, Taiwan—still a disputed administrative division of the People's Republic of China—was a conservative democracy that was largely closed to the outside world. At the time he arrived in America, Hsieh was by and large unversed in the discourses of Western contemporary art. Yet his performance Jump Piece (1973)—executed the year before he left Taiwan and saw the artist leap from a second story window in Taiwan, shattering both ankles—shared affinities with the (real or fictional) plunges of both Bas Jan Ader and Yves Klein, who were equally unaware of the work of Hsieh.

Hsieh's One Year Performances were rule-based works which began with a declaration of intent complete with legalistic apparatuses of proof. The first of Hsieh's lifeworks was One Year Performance 1978–1979 (or Cage Piece) (1978–1979), for which the artist spent a year confined to a cell-room measuring 11'6" x 9' x 8', constructed of pine dowels and two-by-fours in his studio.

His friend Cheng Wei Kuong brought him food, clothing and removed his waste, while a lawyer certified that every joint of the cell was tied with a paper seal and remained intact upon the culmination of the performance. Vowing not to converse, read, write, listen to the radio or watch television, Hsieh's was a seemingly self-punishing exercise in boredom which was both enormously physically and psychologically trying.

Today, Hsieh is positioned within a global history of artists who have marked and bent time such as Joseph Beuys, On Kawara, Vito Acconci and Marina Abramović.

The remaining documents of this performance are black and white photographs of the artist in his cell, bare but for a sink and basic cot. Echoing the disciplinary atmosphere of the cage, Hsieh wore prison-like garments embroidered with his name and shaved his head at the onset of the performance—his unkempt, growing hair showing the passage of time.

Yet in his prison, Hsieh was his own guard, exploring the conditions of what he viewed as the basic struggle of living. Photographs show the artist sleeping, washing, carving notches in the wall to mark the days, and sitting with his head in his hands, willing the days, weeks and months to pass.

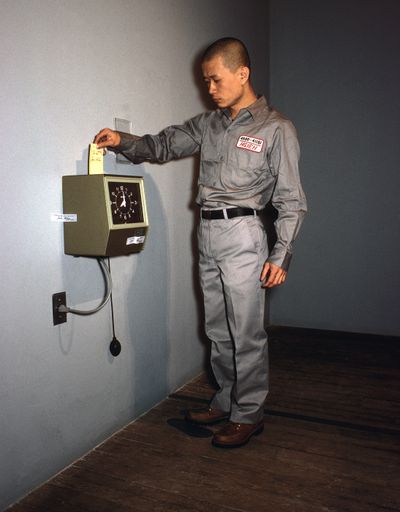

For One Year Performance 1980–1981 (or Time Clock Piece) (1980–1981), Hsieh vowed to punch a time clock in his studio every hour on the hour for one year. Immediately after punching in, Hsieh was to leave the room, meaning each occurrence required wakeful, conscious action and a constant disruption of rest. The public was invited to view the performance on 14 predetermined days.

Again, Hsieh shaved his head at the onset of the work and captured himself on a single frame of 16mm film at every punch over the course of the year. The resulting six-minute film shows his wildly growing hair, weary eyes, and seemingly trembling body standing next to the clock, the hands of which rapidly and indifferently spin. In Venice, the frames of the film are displayed on the walls in stark, serial rows. Visible evidence of severe sleep deprivation on Hsieh's person shows how the passing of time leaves its mark on the regulated and restrained body.

Similar physical degradation was seen in the subsequent One Year Performance 1981–1982 (or Outdoor Piece) (1981–1982), for which Hsieh spent a year on the streets of Manhattan without taking shelter of any kind; including boarding a vehicle or taking refuge in a doorway. Over the course of the year and harsh undulation of coastal seasons, the meeting of basic human needs was translated into an artwork—and one observed mostly by Hsieh himself. Minutely detailed maps of his daily wanderings and photographs of life on the street were kept as records and are shown in Venice.

At a talk with Heathfield at Hong Kong Arts Centre in March, Hsieh screened a short film documenting Outdoor Piece. In addition to his daily activities, the film shows an incident when law enforcement officers, thinking Hsieh a vagrant, attempted to force him indoors. Hsieh's screams and flailing resistance—painful to witness—are a reminder of the law's violence against marginalised bodies. The officers eventually allowed him to stay outside in a fascinating case of state respecting art outside institutional or recognisable forms.

The next year, for Art/Life One Year Performance (or Rope Piece) (1983–1984), Hsieh tied himself with an 8-foot-long rope to artist Linda Montano whom he was not allowed to touch for one year. Hsieh has said that his choice of a year for his lifeworks reflects the movement of the earth around the sun—an ode to humankind's binding to cosmic order.

After this fourth work (which unsurprisingly resulted in a long-lasting rupture in the artists' relationship), Hsieh became a known name in the New York art scene. Yet his next piece countered this visibility: for One Year Performance 1985–1986 (or No Art Piece) (1985–1986), Hsieh vowed to disengage from art. In a statement, Hsieh declared: 'I not do ART, not talk ART, not see ART, not read ART, not go to ART gallery and ART museum for one year. I just go in life.'

Though unverified by notaries like his other performances, Hsieh's performance pointed to the ambiguous perimeters of aesthetics—in order to avoid art, one must first determine what it is and where it lives. For Hsieh's final lifework in 1986, he published a statement that read: 'I, Tehching Hsieh, have a 13 years' plan. I will make ART during this time. I will not show it PUBLICLY.' On New Year's Day 2000, Hsieh revealed the culmination of the performance in Manhattan: a poster that read 'I KEPT MYSELF ALIVE', underlining the belief in the simultaneity of art and life that encapsulates his practice.

Hsieh's work points to the utopian idea of 'free time'

Independent of the gallery scene in New York in the 1970s and 80s, Hsieh was unbound by institutional determination and able to work beyond the confines of market-fit contemporary art. As Hans Ulrich Obrist stated about the artist 'While many were sprinting, he did marathons.'

Today, a resurgence of interest in performance art in the past two decades (art institutions historically avoided it due to the unpredictable nature of its economies and audiences) has enlivened a discourse that has expanded the legibility of Hsieh's works, which are influential to a new generation of performance and body artists—particularly in China and Taiwan.

In 2012, Hong Kong non-profit Para Site staged Taiping Tianguo, A History of Possible Encounters, (12 May–28 August), a travelling exhibition drawing connections between Hsieh, Ai Weiwei, Frog King Kwok and Martin Wong; four artists of Chinese, Hong Kong or Taiwanese descent who were involved in New York's art scene in the late 1970s and 80s.

The show pointed to intersections of the artists' lives in New York, including photographs by Ai in which Hsieh appears, or Kwok's assistance with Hsieh's lifeworks, to highlight the casual network and underground economy of diasporic artists in the American metropolis. Today, Hsieh is positioned within a global history of artists who have marked and bent time such as Joseph Beuys, On Kawara, Vito Acconci and Marina Abramović (the latter of whom once referred to Hsieh as the 'master' of performance art).

Twofold concerns with the conditions of outsider life and the regulation of time make Hsieh's works from the 1970s and 80s particularly pertinent in contemporary life. Today, an increasing delineation is drawn between those perceived to belong (citizens) and those thought of as fugitive beings (non-citizens).

Hsieh's embodiment of the experience of the latter is useful to remember when considering the millions of people who are migrants by necessity, or the violence of extreme restriction of movement between borders. His works (particularly Clock Piece) were also foreseeing in their critique of the blurring of private and public time.

Time, first loosely measured with the natural rotation of the earth and curves of sunlight, has been increasingly commoditised over the course of civilisation. With an emphasis on efficiency and speed, the momentum of the industrial revolution both regulated and accelerated time as a tool for productivity.

The ubiquity of smartphones has sealed this arrangement. Surrounded by screens, when is one today not reachable by capitalistic forces—when does one truly 'punch out'? As Heathfield writes in Out of Now, 'In the cultural logics of late-capitalism, time itself is a commodity that must be exploited to its maximum potential.'

Hsieh's art, he writes, 'was incredibly prescient in the understanding that the technologies of capitalism would capture and accelerate life itself, turning sentient experience into productive labour.' By erecting his own prisons, both figurative and literal, Hsieh's work points to the utopian idea of 'free time': unregulated, unbound to commerce or unburdened with the urgencies of survival. —[O]