Samson Kambalu Takes Collective Memory to Task

Two gigantic elephants command attention when entering New Liberia (22 May–5 September 2021), Samson Kambalu's solo exhibition at Modern Art Oxford, curated by chief curator Emma Ridgway.

Exhibition view: Samson Kambalu, New Liberia, Modern Art Oxford, Oxford (22 May–5 September 2021). Courtesy Modern Art Oxford. Photo: Mark Blower.

Located in the Upper Gallery, the Drawing Elephants (2021) are made from black Oxford University graduation gowns that have been taken apart and reassembled as new skins.

They reflect Kambalu's interpretation of Malawian Nyau performances, such as those performed for the traditional Gule Wamkulu ('Great Dance'), where masks were used to 'communicate ancestral wisdom [and] generate harmonious communities in times of transition.'1

Nyau culture has long been a source of inspiration for Kambalu. In an article published in African Arts, photographer Douglas Curran defines it as 'the primary spiritual practice of the Chewa people of central Malawi.'2

In this frame, Kambalu's re-appropriation of Oxford gowns confronts what Curran goes on to explain: that in the colonial era, Christian missionaries and colonial administrators viewed the indigenous culture of Nyau as an exhibition of 'obscenity', 'sensuality', 'cruelty', and 'evil'.3

The high ceiling of this former brewery lends itself to these monumental elephants. They are surrounded by seven colourful flags from Kambalu's 'Beni Flag' series (2020), recently showcased at Kate MacGarry in London, and two wall hangings—Elephant Quilt I and Elephant Quilt II—each made up of 12 flags.

Beni, meaning 'band', is a form of syncretic dance from South Africa, which partly parodies the marching displays and parades of German and British colonial forces. Each flag's playful title—including Paper Cup Nation and Supermarket Republic (both 2021)—seems to reject the false promises of 'nation' states, while proposing new ways to think of collective identity, described in the exhibition note as a 'united diasporic global community.'

Two text-based light sculptures recalling cinematic marquee signs designed to draw in movie audiences in 1960s America, complete this first gallery grouping. Drawing in the 18th Century (Synopsis) (2021) and Sculptor (Synopsis) (2021) describe actions of drawing and sculpting that take place in two of Kambalu's films in the final gallery, where ten films of no longer than one minute each surround a central podium.

Using play and satire to engage in radical acts of public expression, Kambalu destabilises narratives that have been handed down unquestioned.

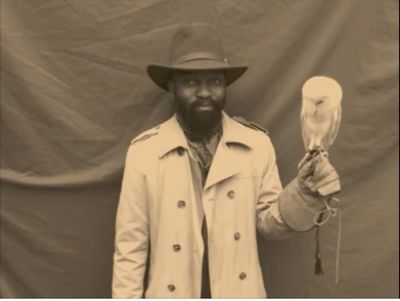

From the 'Nyau cinema' series (2012–ongoing), scenes have been spliced together in a manner that recalls the manual editing of projectionists from Kambalu's Malawian childhood, capturing the artist walking, in vaudevillian style, through buildings and parks, or dragging a heavy chain by the docks.

Techniques of cutting and reconstructing drawn from early cinema run through Kambalu's practice: a process that considers history as a series of fragments that carry epistemological assumptions and obfuscations to be challenged.

Take the installation surrounding the 3D-printed model of Kambalu's winning Fourth Plinth design for London's Trafalgar Square in 2022 (Antelope – Ghost maquette for the Fourth Plinth, 2021), in the Middle Gallery.

On red and blue wallpaper-emblazoned walls, black and white images and two-line dialogues comprising Kinetic Church (Providence Industrial Mission) (2021) pay homage to John Chilembwe, a Western-educated missionary who led a 1915 uprising against the British in Malawi.

To honour Chilembwe's 'radical political action', which resulted in the destruction of his church and execution, Kambalu also highlights 'the underrepresented people in the history of the British Empire in Africa, and beyond.'4

Using play and satire to engage in radical acts of public expression, Kambalu destabilises narratives that have been handed down unquestioned. With a fractured mode of storytelling running through the artist's practice, it is up to the viewer to build meaning in this comprehensive show, which raises questions about the construction of history and challenges its linearity in turn.

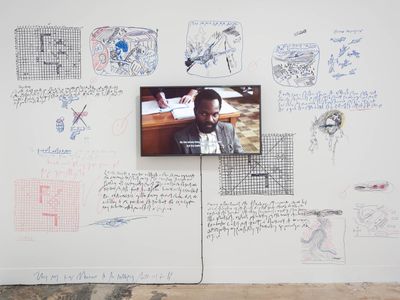

This invitation is offered effectively in the smaller interconnected space within the Middle Gallery, which hosts the most thought-provoking installation on view. Here, Kambalu shifts from making history's unseen protagonists visible to challenging those who seek to manage visible—and open—legacies.

Over two hours long, the film Sanguinetti Cell (2021) reenacts the trial that Kambalu faced for presenting Sanguinetti Breakout Area (2015) in Okwui Enwezor's 56th Venice Biennale, for which Kambalu photographed the entire protest art archive of Italian Situationist writer Gianfranco Sanguinetti, prompting the writer to sue.

Kambalu won his case by arguing that Sanguinetti's archive was collectively owned, while questioning the irony of being sued by a member of a movement that advocated appropriation and satire. In this show, the film is framed in a space replicating a prison cell, with scribbles on the wall by Kambalu drawn from Sanguinetti's archive and the rephotographed book Sanguinetti Theses (2015) on display. —[O]

1 Samson Kambalu: New Liberia, Exhibition Notes, Modern Art Oxford website, https://www.modernartoxford.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Samson-Kambalu-New-Liberia-Exhibition-Notes.pdf

2 Douglas, Curran. 'Nyau Masks and Ritual', African Arts, Vol. 32, no. 3 (1999): pp. 68–77, www.jstor.org/stable/3337711

3 Ibid.

4 Samson Kambalu: New Liberia, Exhibition Notes, Modern Art Oxford website, https://www.modernartoxford.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Samson-Kambalu-New-Liberia-Exhibition-Notes.pdf