Yinka Shonibare (MBE, RA) at Pearl Lam Galleries

This interview is a transcript of a conversation that took place between Yinka Shonibare MBE, RA and Anna Dickie at Gillman Barracks in Singapore on the occasion of the opening of Shonibare's solo exhibition at Pearl Lam Galleries, Childhood Memories (21 January to 31 March 2016).

Image: Yinka Shonibare MBE RA. ©Royal Academy of Arts, London. Photo: Marcus Leith, 2015.

In an ironic twist, it is the work of Yinka Shonibare MBE RA who I am most reminded of when visiting the National Gallery Singapore and spying the work, Morning (1960–1963) by Chuah Thean Teng. The National Gallery work makes reference to batik, a fabric Shonibare uses in his work. While Teng's early use of wax-dying batik techniques is recognised for influencing a generation of Malaysian and Singapore artists, there is no known link with Shonibare.

Yet, that a work by a modern painter from Malaya exploring the material possibilities of batik in the 1960s should trigger associations with the contemporary work of a multi-disciplinary conceptual British-Nigerian artist, reflects some of the twisted and tangled notions of identity and culture that Shonibare has been exploring throughout his long career.

In what is now a well-known story, Shonibare—who was nominated for the Turner Prize in 2004 and became a Royal Academician in 2013—began using batik fabric after his professor at the Byam Shaw School of Art in London challenged him to create, 'authentic African work'.

In a quest to understand what that meant he explored the origins of the archetypal, 'authentic' and colourful fabric that is so often associated with African identity. To his amazement he discovered that the fabric's origins are arguably Indonesian (hence the link with Chuah Thean Teng's work). It is believed that batik design was appropriated by the Dutch and used to create mass-produced fabrics eventually sold to colonies in West Africa, and where it became associated with the African independence movement in the 1960s.

My parents wanted me to be a lawyer, so in a way choosing to do art was my way of rebelling against them and developing my own identity.

The fabric, which is a signature motif for the artist, appears in Shonibare's most recent work, which is on display, across two spaces, at Pearl Lam Galleries in Singapore until 13 March 2016. Included in the exhibition are four large sculptures and also several screen prints, each of which draw on the artist's memory of his childhood in Lagos, Nigeria.

Shonibare was born in Britain, but his family moved to Lagos when he was three years old. He returned to London at the age of 17 to complete his studies. This new work marks a departure for the artist, whereby he has begun to present dreamlike fantastical scenarios that explore this half-remembered childhood, as well as the constructed and fictitious memories of folklore and tradition.

One sculpture shows a headless child dressed in a sumptuous costume created from the batik fabric, and bent over backwards beneath a tower of books that balance precariously on his chest. Another sculpture, which sits in the centre of the space, presents two headless children—as it turns out, twins—riding an enormous butterfly.

Shonibare defines the latest trajectory of his work as partly a reaction to the current global conflicts, possibly an act of escapism, drawing connections with the Surrealist interest in the unbridled imagination of the subconscious.

Art is not science, that is what is so good about it.

I walked into this space today, and it immediately triggered, for me, an association with the imaginary world of Lewis Carroll's 'Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'. This was a book I grew up with. Why now has it been important for you to explore the realm of imagination for this show?

Because of the current global conflicts. A lot of my work has actually been connected to ideas of politics in the past, or to contemporary discourse about identity, but then recently a lot of my work has been reacting to current affairs, reacting to the violence being reported globally. And the way I can handle this, and get my head around it, is to return to the idea of the self, or the individual. It is about a return to this notion of one's own fantasy or imagination.

It was out of the First World War, the Dada artists emerged. They began to challenge the system and structures of the world around them at that time. They used their imagination (perhaps as an escapism from their current reality) and this developed into Surrealism.

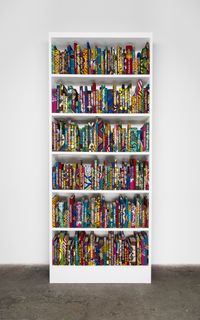

Your work has before used art historical or literary references, but here I understand you also wish to reference your own history. The work, Boy Balancing Knowledge (2015), presents a child figure balancing a huge tower of books on his chest. I was looking at the title of the books, and there is really a range of books, from 'Alice's Adventures in Wonderland', to 'Gulliver's Travels' to a book about economics. And I was interested to know why these particular books?

They reflect the books that were in my house growing up; they are the books my parents had in their house. When I was growing up, I was always forced to read books. And even when I was at school, I was still being forced to read. I was continually asked 'What are you doing? Why are you not reading?'.

In a way that work reflects upon my anger at that time, my childhood rebellion which arguably led to my pursuit of the arts. My parents wanted me to be a lawyer, so in a way choosing to do art was my way of rebelling against them and developing my own identity. But actually I came back to reading books through my art.

It is interesting to talk about rebellion, because you have described your art as a 'Trojan Horse', as a way of rebelling from within the system.

I think, in a way, you have to be creative about how you rebel, because if you become too aggressive and too didactic then you are just making people become defensive and it isn't very effective. So you need to find a more engaging way to express yourself and your view. In essence, like the Dada artists who chose their mode of expression through art.

You are working for the first time with print. You have worked with so many different mediums over your career to date: film, photography, sculpture. How would you describe your experience of working with print?

I enjoy the process of print very much. I enjoy drawing. I started out as a painter, so for me it was really a bit of a circle, and about going back to my own origins in art. It is a much more intimate way of working and I really enjoyed that. When I make the larger pieces, they are more about design teams and me directing the making. Whereas for these works it is all about being hands on. There is a relationship between both ways of working, but it is actually good to go back to doing something so intimate.

It was interesting to explore how I might go back to making prints, but still ensure the end result felt like my work. That was a challenge. I needed to create a new language for my prints and through the process of creating the works I felt I did get there.

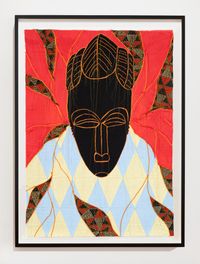

To me there is some very obvious links between the prints and your other work: the hint of batik in one work, and the presence of what appear to be Victorian figures. But can you please tell me how you specifically see these works as linking to your earlier work?

In these particular works I tried to produce pieces that relate to my history, but still have a universal flavour. I never produce racially specific works because there is too much prejudice in the world. However, take the twin figures you see in the prints. For me, they are very specifically an African reference. In Nigeria, particularly within the South, twins are regarded as having special powers, so you have to treat twins very well, as it will bring good luck to your family.

If you treat twins badly, that will bring bad luck to your family. So the images you see in those prints—which look like images of Victorians—are actually the statues of the twins customarily given as a gift to the mother of twins in Nigeria. Essentially it is combining this very African idea with Victorian images. It creates a juxtaposition.

Tell me about some of the other marks or patterns in the prints. For example, the scallop type shapes that appear?

I liken them to musical improvisations. If you listen to music, you will hear notes, but then the instrumentals in-between are usually quiet abstract. I think you just feel these things. It is to do with tonal differences, tonal ranges in the colour you are using. It is to do with form, and the relationship between things. It happens instinctively, and you get to a point when you know. Art is not science, that is what is so good about it. —[O]