Beyond Influence: The Legacy of Korean Monochrome Painting

'One thing to remember about Tansaekhwa is that it was never an official movement,' Joan Kee, Associate Professor of Art History at the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor, explains in an email interview. 'There was no manifesto, no declaration—not even a series of exhibitions consciously organized under that rubric.'

Otherwise known as baeksaekpa (the School of White) or Dansaekwha (after the South Korean government revised its Romanisation system in 2000), Tansaekhwa describes the Korean monochrome painting movement born out of the late 1950s and which had fully emerged by the mid-1970s. It is a term Kee calls 'a post hoc convenience'—one 'retroactively applied since roughly the 1980s to refer to a large constellation of paintings that tended to be shown together in some of the first major overseas exhibitions of contemporary Korean art.'

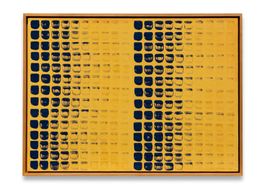

Nevertheless, the term has stuck. In 2014, it was used to frame three exhibitions dedicated to the genre, in which a core group of artists circulated. Chung Sang-hwa, Ha Chong-hyun, Lee Ufan, Park Seo-bo and Yun Hyong-keun appeared in From All Sides: Tansaekhwa on Abstraction (which added Kwon Young-woo to the mix), at Blum & Poe (curated by Kee), The Art of Dansaekhwa at Kukje Gallery, curated by Yoon Jin Sup (which added Kim Guiline and Chung Chang-Sup), and Overcoming the Modern | Dansaekhwa: The Korean Monochrome Movement at Alexander Gray, which also featured Hur Hwang and Lee Dong-Youb.

Art Reoriented’s Sam Bardaouil and Till Fellrath curated the latter exhibition, and also took part in a one-day symposium held as part of Kukje Gallery’s show. Titled Why Now? it was themed around the questions of why Tansaekhwa has again “surfaced as a topical school of art whose ideas remain vital to artists and engaged citizens alike, and why it is still important to argue for Tansaekhwa’s historical place vis a vis international art movements.” Bardaouil and Fellrath’s discussion was moderated by Doryun Chong, chief curator at M+, and also included Lee Ufan and Alexandra Munroe, Samsung Senior Curator of Asian Art at the Guggenheim Museum. It centered on the importance of Tansaekhwa in the context of the 21st century’s new audiences.

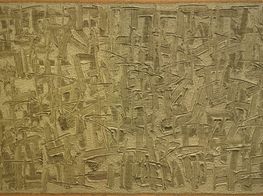

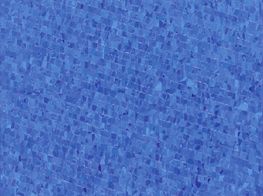

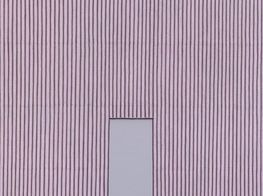

Of course, the question of how Tansaekhwa fits into the global frame is a pertinent one, given how the movement is aesthetically aligned to American abstract expressionism and colour field painting. After all, this was a movement crafted by a postwar generation, one that rejected academic concerns—from traditional subjects (figure and landscape) to material approaches—in favour of a more mediated study into the tensions and possibilities from negotiating pure colour, form and material on canvas. But at the same time, what sets this movement apart is the continued perspective of ink painting as both contemporary and avant-garde: a persistence Kee notes lasted well into the 1960s and 'profoundly affected generations of artists who considered ink painting not in terms of its symbolic potential or even as a technique, but as an opportunity for artists to challenge what they really knew of pictorial space, the properties of materials, surfaces, edges, and frames.'

Indeed, when thinking about how Korean monochrome painting might fit into the wider canon of abstract expressionism and colour field formalism without falling into the frame of deviation, Bardaouil’s and Fellrath’s avoidance of the term 'influence' comes to mind. Discussing Tansaekhwa in an interview with Whitehot Magazine, they explain how using the word 'influence' when discussing the western input into the development of monochrome painting in Korea 'implies a passive copying on behalf of the "influenced".' Rather, the curators chose to see the exploration of Tansaekhwa 'as a process of negotiation whereby the artists had the freedom and sensitivity to a wide array of formal, aesthetic and political factors which they perceived and employed as catalysts in formulating a unique language that is rightfully theirs to contribute to the advancement of contemporaneity in their immediate environment.'

This immediacy was postwar Korea: a nation that only gained independence from Japanese rule the year World War II ended, 1945, and went on to experience the devastating Korean War between 1950 and 1953, before becoming fully entrenched in U.S cold war policies in Asia. Indeed, South Korea’s relationship with Japan and the United States fed into cultural activities at the time—Japan, for instance, a hotbed of avant-garde activity, was viewed during this period as a gateway to the international art world; a nation with close ties to America, with whom Japanese practices engaged in a certain level of cultural exchange. (Yoko Ono’s historic performance, Cut Piece, being a case in point. It was filmed in New York in 1965 but was originally performed at Kyoto’s Yamaichi Concert Hall in 1964.)

During this period, Tansaekhwa was not the only burgeoning movement: concurrently, another scene characterised by installations and happenings and spearheaded by the 1967 Young Artists Coalition, was also blossoming. And while both movements were indeed spurred by a desire to break with traditions, they also reflected what contemporary Korean art was responding to, or indeed enacting, at the time: a delicate yet vital kind of cultural dialectic that Kee describes in her book Points, Lines, Encounters, Worlds: Tansaekhwa and the Formation of Contemporary Korean Art as, 'another manifestation of what had been an uneasy symbiosis between the desire to take part in a larger international art world and to assert the existence of a distinct and autonomous cultural self.'

In 1968, for example, the Fourth Contemporary Art Seminar in Seoul was held, during which artist Jeong Gang-ja covered her bare body in balloons and invited participating performers and audience members to pop them to the music of John Cage and Harry Partch. Meanwhile, as Rauschenberg ignited something in a generation of Chinese artists, so Mark Rothko made his mark on the work of Yun Hyong-keun, who was, in turn, compared to Morris Louis by a Tokyo-based critic, Joseph Love, in 1975.

In this, the focus on Tansaekhwa in 2014 is, as Kee describes it, 'a wakeup call for anyone who might still think of abstraction as a Western phenomenon.' At the same time, it is an invitation for viewers to 'consider what we think we know based on our own limited capacity for seeing.' Quoting Kee, the real opportunity in this renewed interest in the movement (there was a brief attempt in the mid-1990s to nurture attention) is the chance to emphasize what these works mean and why they were made. After all, as Kee explains: 'One of the fascinating parts about Tansaekhwa is that the entire interpretation can change depending on what you choose to focus on first.'—[O]