Lee Ufan

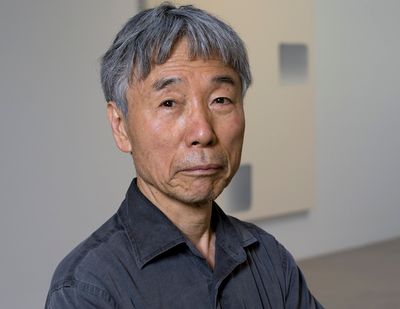

Image: Lee Ufan. Photo: G.R Christmas. Courtesy of Pace Hong Kong. © Lee Ufan

Image: Lee Ufan. Photo: G.R Christmas. Courtesy of Pace Hong Kong. © Lee Ufan

Nowadays, Korean-born artist Lee Ufan needs little introduction. The combination of the opening of his own Tadao Ando-designed museum at the Benesse Art Site, Japan in 2010; his 2011 retrospective at the Guggenheim Museum, New York; and his major show at the Château de Versailles in 2014, have all meant that in recent years Lee Ufan has deservedly risen to prominence in the contemporary art world.

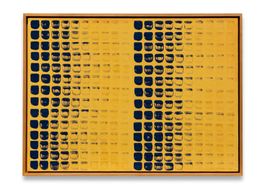

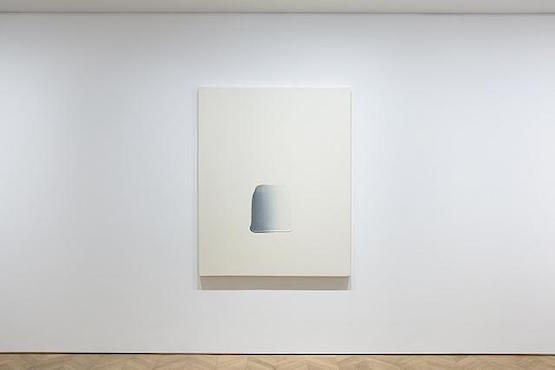

Acclaimed for his founding role in the Japanese Mono-ha movement and pivotal contributions to the Korean style of Dansaekhwa, Lee's serene white canvases illuminated by expressive touches of paint, and large site-specific sculptures made from stone and iron have become iconic. Despite practising art for over 50 years, in 2015 Lee has shown no signs of slowing down.

This year alone Lee is the subject of exhibitions at Lisson Gallery and Pace in London, as well as Pace Gallery in New York and SCAI the Bathhouse in Tokyo, and he also participated in Dansaekhwa, a group exhibition dedicated to the art movement, which took place in Venice during the 56th Venice Biennale.

Most recently, Lee opened a show of new Dialogue paintings, his current on-going series, at Pace Hong Kong and it was while Lee was in the city that Ocula contributor Katie Fallen was able to speak with the artist.

Lee began his Dialogue series around 2006; he creates each work by placing one to three touches of pigment, mixed with glue and crushed stone onto a crisp white canvas. With the intention of developing of his practice further, Lee spoke of how he was driven by a desire to make his work more powerful and fulfilling. While Lee's practice is often aligned with literature, philosophy and Eastern influences, the artist refuses to reify his work in such a way.

According to Lee, he does not begin his creative process with an idea or image he needs to express; rather he feels he is the conductor of his materials, an equal to them, communicating with the canvas or sculptural objects to create his works. This connection was prevalent throughout our conversation; Lee would continually look at the painting hung directly in front of him when he spoke about his practice, gesturing towards the canvas, as though he were bringing the work into the dialogue. It was here, sitting with Lee and his paintings, we discussed his experiences in the contemporary art world, how he perceives his work in the context of today and where his latest works sit in the long trajectory of his practice.

I think that within the artist community there is no such a thing as globalism. Each artist, they are working for themselves on their own creation. The most important thing is the artist himself; he should work with his own personality.

KFYou have been creating works for over 50 years and as a consequence you've been witness to considerable change in the art world, seeing it shift from the local to the global. How has this influenced your practice? Is there a particular change in the art world that has been especially influential?

LUThat's a very difficult question. Actually, it was my first time in Paris for the international biennale in 1971, after which I visited the United States; at that time, the world seemed really big, but I had the chance to meet a lot of artists. It had a great impact and gave me a lot of inspiration. Over the past 50 years, I have travelled a lot and gained a lot of different influences; these have merged and at last I find my world, the world of Lee Ufan. During my trips overseas, I find that people might change and actually everybody experiences different things. It is these experiences that make a person have the feeling they can create their own world.

Globalism not only allows the sharing of information with different artists, it is also about how you are going to work with them, meet with them, move with them. It is not only an information exchange, it is a personality movement; when you meet someone and see their personality you ask, 'How can you move together?' This is something I would like to say about globalism—it is not only about information; it is about people and their personalities, the movement and the meeting.

KFIn your experience, do you feel that globalisation has been beneficial to the art world? And influenced the development of your practice?

LUActually, I think that within the artist community there is no such a thing as globalism. Each artist, they are working for themselves on their own creation. The most important thing is their own personality—this is very important. Even in some of the articles written, there might be trends, there might be movements, but the most important thing is the artist himself; he should work with his own personality.

KFBuilding on the emphasis you place on the artist's personality in the global art world: do you feel there is a way the art world can move beyond the continued interest in nationality-based categorisation of artists?

LUFor example, some European and American critics, they will still say this person is from Asia; they will classify me or categorise me as not from the West. Actually, I'm not interested, I do not want to make a comment on what they have written. I always ask myself, 'What can I do in the contemporary? How can I improve my contemporary art and myself?'

I don't think it's only me but also other artists, such as Anish Kapoor and Anselm Kiefer; they are always asking themselves, 'How can I answer my own questions?' This is something that is important. I cannot give you the best answer or the correct answer, but this is something I keep in mind. I have questions and issues I want to answer; I want to see what I can do for contemporary art instead of caring about how critics will categorise me.

KFYou continue to produce both sculpture, such as the large-scale site-specific installations in your exhibition at the Château de Versailles last year, and paintings—how do you feel these two practices inform one another? Do you consider them as similar or separate elements in your oeuvre?

LUPainting and sculpture: painting is on the side and sculpture is something with dimensions. The only issue, and the biggest issue for me, is whether I can paint or not. If there is no canvas, a wall would be good. For sculpture, it is whether I can create or not create. When I am making a creation with iron and stone, [one question is] whether I should place it indoors or outdoors. The most important thing is space and the atmosphere of the space. How are these things going to see each other? How are people going to see the iron plate and stone in this space? What is the relationship between the creation and the space? These are the most important issues to me. Painting and sculpture, they are the same; the only issue is whether I can do it or not.

Modernism is about the almighty; the medium is all over, [the artist makes a] colonial claim, asserting their thinking as everything. And now, my issue is the canvas, the exterior. Canvas is canvas; Lee is Lee. Canvas is a [point of] contact, and I challenge it to a dialogue with just a few touches and responses. This is the contemporary issue. Painting and sculpture, made and unmade, and now space and place; because my work is not just an object, it is an object and space together, made and unmade, the link between them is my issue.

KFSo your practice is focused on exchange, experience and fluidity. Our world has become increasingly virtual or digital. What impact, if any, has this had on your practice, which places emphasis on the materiality of the work and parity of artwork and viewer in reality?

LUNowadays, there is a lot of information flow. You find things are very flat nowadays, and everybody is more or less the same. There is nothing called reality. Some artists are using a lot of videos and photos; this is fine but me, I am a primitive, which is the complete opposite to the virtual world. I think I might be a mismatch with the time of now, because I want to do something with my hands, to create something real. I want to make something in reality, and this is my way of doing my own creations.

I cannot say if I can change the behaviour of others. The only thing I am interested in is using my hands; me as a person, doing something real. I am simply interested in using my hands to make a creation. I am not interested in how much my creations are worth, this is not my concern. My concern is how my creations—with the atmosphere, with the space, with the area—are going to stay together and communicate.

KFYour works really do give viewers the space to think, beyond the virtual world.

LUYes, this is very important. Even little children, when they see my creations, some of them want to touch it because there is a reality there. Something virtual, no one wants to touch it.

KFLooking more closely at your recent Dialogue paintings, please could you explain how they have developed from your earlier works, such as From Line, From Point and From Winds?

LUThe only difference that I think should be noticed is the strokes. In the seventies, I used small strokes and now I use big strokes. In the seventies, my From Point works were relatively small and I used a lot of blue and orange. Some people would say the blue means the sky and the orange means the earth, but actually that's not an important issue in my painting. In the eighties, I had a big change in my work, I started to mix the colours together, and use a lot of grey. Later on people started saying, you're only using grey. Actually the most important thing is the stroke; colour has no meaning in the work.

—

Lee Ufan: New Works, until 9 January 2016 at Pace Gallery, Hong Kong. —[O]