Cinga Samson: ‘a different conversation on representation’

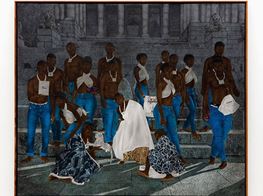

Cinga Samson. Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin. Photographer: Guillaume Ziccarelli.

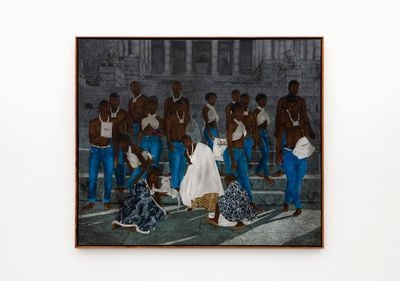

Cinga Samson. Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin. Photographer: Guillaume Ziccarelli.

Cinga Samson's paintings lay bare the complex relationship between contemporary life, African traditions, globalisation, and representation. His strikingly sombre portraits contain similarities to those of contemporary painters such as Toyin Ojih Odutola, Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, Kehinde Wiley, Florine Démosthène, and Tunji Adeniyi-Jones—all of whom reify black bodies by inserting them into a wider and more nuanced art historical narrative that has often omitted these representations.

Reminiscent of Northern Renaissance portraiture, anonymous figures appear in heroic poses as a way to give them both autonomy and authority, often starting each work by painting himself. Working predominantly in oil, Samson brings together realism with fantasy to celebrate youth, adorned with familiar signs and symbols from everyday life. From Nike trainers and silk scarves, to Louis Vuitton coats and gold chains, these are adornments that, as Gabriel Ritter, curator, and head of contemporary art at Minneapolis Institute of Art points out, 'celebrate an aspirational vision of material wealth and luxury', while the figures' 'brooding, introspective gaze' rejects superficiality. Samson thus invites viewers to go beyond the image's surface and into an intensely personal universe.

In Ivory IV and V (both 2018), a figure dressed in a gold and white silk jacket with cosmological motifs stands against a rock-strewn seascape holding a white lace fan, white blank eyes staring onward. Besides subtle variations in vegetation, the most noticeable difference between the two paintings is a pair of red converse trainers slung over the left shoulder of the figure in Ivory IV.

There is an otherworldliness to these figures, who appear as if they have emerged from the sea—a composition that recalls the mythical water spirit, Mami Wata (Mother Water), celebrated throughout much of Africa and by the African diaspora, and who is 'at once beautiful, protective, seductive, and dangerous'.1 Mami Wata has long been a subject of exploration by artists across generations, in discussions ranging from politics to abstraction. Race and cultural production undoubtedly affect the aesthetics of representation, but in the paintings of Cinga Samson, identity politics shifts towards a more nuanced reading of the black male body that is rooted in the present, while moving between memory, spirituality, and lived experience.

In the following conversation, Samson, whose first exhibition in the U.S., Amadoda Akafani, Afana Ngeentshebe Zodwa (men are different, though they look alike) is opening at Perrotin in New York (22 February–11 April 2020), discusses portraiture as a mode for celebrating black beauty, and reflects on what it means to be a young African man today.

In this new body of work, I am exploring what it means to be yourself and really celebrate being a young African man at a time when we can be ourselves after such a long history of being deprived and repressed.

JDYour early work focused on still life, as seen in your series of large-scale painting series from 2015, 'Lord forgive me for my sins 'cause here I come', shown that same year for the exhibition Thirty Pieces of Silver at Blank Projects in Cape Town. Can you elaborate on your interests in Dutch Golden Age painting, nature, and the biblical connotations present in the series' title?

CSThe title comes from the biblical story of Judas who betrayed Jesus to Roman soldiers for 30 pieces of silver. He pointed out who Jesus was by giving him a kiss, hence making him known to his captors, and was later killed.

I found this relevant to the situation I was in at the time, as a child growing up unappreciated in the post-apartheid years. I lived in a township far away from Cape Town in a context created by the apartheid movement to segregate people. Whilst apartheid doesn't formally exist, the structures still exist and favour whites over blacks. I felt betrayed by my city—underappreciated even though I am from there, and I likened that situation to the situation of biblical betrayal and not being seen. It didn't matter about working hard, being serious, or expressing kindness, there was still rejection on a lot of levels. This is where the ethos of Thirty Pieces of Silver came from. I was speaking not just from my individual experience, but for other black kids who might feel betrayed and unseen in this context.

Still life and this love for flowers came from my biological mother and my stepmother. Additionally, I played with other kids near a cemetery and I would see flowers lain at graves; this is also a strong memory. Xhosa people appreciate flowers, which can be found in their poetry, where beauty is likened to living flowers. Once they are picked, however, they become something for the graveside. As opposed to being symbols of love, flowers are closely associated with death, and their decay also becomes a relevant symbol for life's struggles, as well as of death and rebirth.

Once I began to venture outside of my township, I became aware of the racial differences in South Africa, the legacies of apartheid, and the nightmare of my reality. These were some of the thoughts coming through at the time, and that informed these works. I now choose to embrace life differently, hence the shifts and evolution of my work to date.

JDThe title of your solo exhibition at Perrotin in New York references the Xhosa proverb, 'amadoda akafani, afana ngeentshebe zodwa', which translates in English to 'Men are different, though they look alike'. How does this phrase inform your current work?

CSThis proverb is specific to my new body of work. It comes from a conversation I had with my father about my realisation that I am in a stage of my life where I am comfortable and happy with who I am—physically, spiritually, and racially. Society has always celebrated a particular idea of masculinity that doesn't take into consideration that men can be feminine, masculine, macho, and so on.

In this new body of work, I am exploring what it means to be yourself and really celebrate being a young African man at a time when we can be ourselves after such a long history of being deprived and repressed. These portraits are rooted in some of these ideas and reject the stereotypes of being from Africa, which has been portrayed as poverty-, disease-, and conflict-stricken.

JDWhat led you to use your own image as a point of departure for your paintings?

CSI accidentally taught myself how to paint in a more traditional way, by depicting male sitters. After two paintings, my model left one day and while walking past a large mirror, I caught a reflection of myself and realised that my image aligned with the kinds of images I wanted to depict.

That's how I began to paint myself. This happened at a time when I began to change the reasoning in my work, and stopped looking outwards to find meaning or validation in what I was trying to do. I want to paint what I enjoy and what I am attracted to, so that's what led me to work in this manner. Even though I'm painting myself, the intention is not to capture a like-for-like resemblance, but rather a figure that I am able to manipulate. This began by chance, but later resonated internally and as I made more paintings. Each figure represents plurality through popular signs drawn from dress codes such as gold chains, Nike and Converse trainers, Tommy Hilfiger sweaters, and so on.

What I do is not motivated by influences that are direct—it's more about an urge I have to paint.

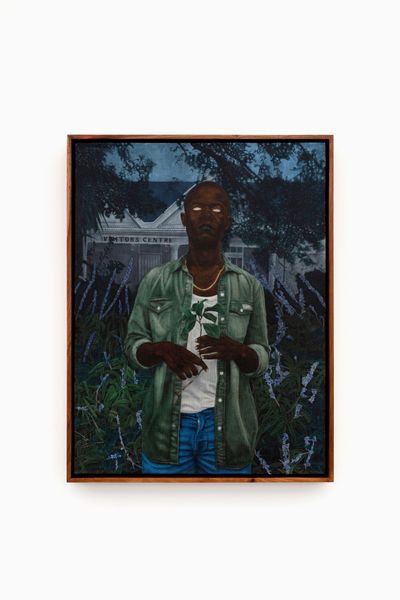

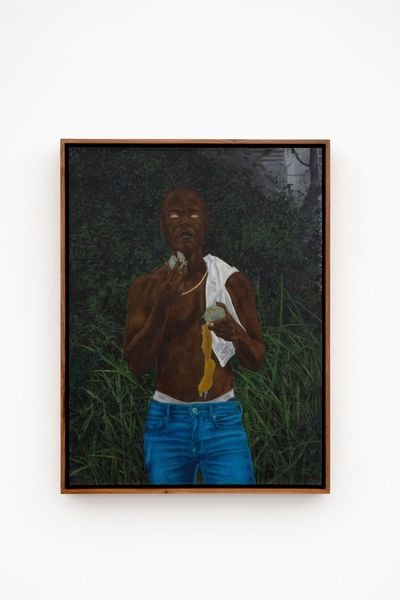

JDYou complicate the gaze of your figures by intentionally removing their pupils. Why have you chosen to do this?

CSThat is a question I've asked myself many times. First, it reminds me of a time in my childhood when I was living in Ethembeni, a village in the Eastern Cape, where my job was to look after cattle along with other young boys. One night, one of the cows didn't come back, and it was our collective responsibility to find the missing animal and bring it back. For some reason, I keep coming back to this particular night with a low moon on the horizon.

This encounter is something that comes to mind when I think about how the eyes are rendered, and the form, composition, and atmosphere that they convey. I don't want this anecdote to feed into certain ideas of being African, like running around in the jungle with lions, and so on; but my experience as a young boy that night comes to mind when I view these paintings. Secondly, what I love about the eyes and absence of pupils is that they convey a dreamlike awareness, as opposed to a gaze that connects them beyond the canvas' frame. Is the figure looking outside of the canvas? These eyes emphasise that the figure is aware, rather than just looking passively.

JDHow do your portraits speak to the nuances of blackness, black body politics, and representation in South Africa and beyond?

CSI am a young black African man who is painting himself, so these politics come into it undoubtedly, but I do want to channel experiences specific to my lived experiences. I'm not just dealing with blackness and black body politics, as my work touches on different subjects as it evolves. In the past I have depicted more familiar things, like flowers, and might return to more of that kind of representation.

I am more interested in starting a different conversation on representation than the ones that already exist. I also want to represent the spirituality of where I am from, while leaving the politics of representation for the audience to interpret. I grew up witnessing rituals and cultural codes that some might view as dark.

JDCan you expand on some of these rituals and cultural codes?

CSThere are so many rituals I witnessed growing up, which are still part of my background as a someone who is of Xhosa descent. These rituals are both seen and unseen, but the first and most significant one happens when a child is born, called imbeleko, when the male or female child is given a blanket and introduced to family members and ancestors. Other rituals happen throughout life, for instance when people are faced with problems or have reached a certain point or doing well, there is a gathering called iti when family members get together to drink traditional beer, goats are slaughtered, and so on—the idea here is to give thanks to ancestors and ask for their guidance.

Some rituals have to do with transitioning from being a boy to a man, such as ukwaluka, which involves going to the mountain or remote bush, where initiations on how Xhosa men behave and carry themselves are taught. This ritual involves being away from one's family, and is a rite of passage. These are some of the rituals I witnessed growing up. They are specific to Xhosa people, and other Ngoni people who live in parts of South Africa, particularly in the Eastern and Western Cape.

JDThe sociopolitical and cultural behaviour of the black male body, particularly those that do not conform, have raised debates around masculinity being 'in crisis'. What is your position on this?

CSIn the future, I don't want to limit myself to representing certain body politics. I wouldn't say that I am at the forefront of black body politics, or that I have a high interest in challenging this. It so happens that I paint myself, and as a young African man, this undoubtedly ties to the political, but I leave this for others to reflect on. I would rather channel the particularities of my experiences specific to the context I grew up in, ranging from spirituality and ceremonial rituals, to the mysticism of all of that, which might seem bizarre to someone who is from a different space. I am not trying to do right by those politics, as I am trying to create my own visual language. I seek to start new conversations around being African, but what I want to represent is an embodiment of the spirit of my people and where I'm from.

To add, I create these figures that fluctuate between human and non-human, so I don't think of them as being framed within this notion of masculinity in crisis. I think there is a current shift in thinking and culture, as well as changes that accommodate new understandings of being a man. Is it a crisis? I would say it is evolving, as opposed to being in crisis.

JDWhat influences shape your painterly practice?

CSWhat I do is not motivated by influences that are direct—it's more about an urge I have to paint. I usually work with an idea and see it through, and it's only later on that I am at times able to make connections to specific experiences, such as my childhood and studies at the Stellenbosch Academy of Design and Photography, and other points in my life. I don't have inspirations specific to key events, people, or books. It's more related to daily life. —[O]

—

1 Introduction, Mami Wata: Arts for Water Spirits in Africa and its Diaspora, Smithsonian National Museum of African Art, https://africa.si.edu/exhibits/mamiwata/intro.html