Michaël Borremans

In partnership with The 21st Biennale of Sydney

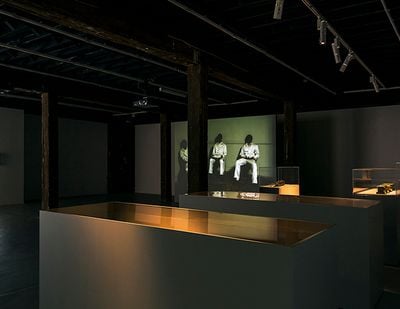

Michaël Borremans, The Storm (2006). Single-channel video, 1:07 mins, looped. Installation view:21st Biennale of Sydney, Artspace, Sydney (16 March–11 June 2018). Courtesy the artist and Zeno X Gallery, Antwerp. Photo: Document Photography.

Michaël Borremans, The Storm (2006). Single-channel video, 1:07 mins, looped. Installation view:21st Biennale of Sydney, Artspace, Sydney (16 March–11 June 2018). Courtesy the artist and Zeno X Gallery, Antwerp. Photo: Document Photography.

Embarking on a career as a painter relatively late, at the age of 33, Belgian artist Michaël Borremans initially trained as a draughtsman and engraver at Saint Lucas in Ghent. On the occasion of his inaugural exhibition Michaël Borremans: Fire from the Sun at the new David Zwirner space in Hong Kong (27 January–9 March 2018), I spoke with Borremans about his practice and his participation in the Biennale of Sydney (BoS) (16 March–11 June 2018).

There has always been something not entirely of this world about Borremans' works. His paintings depict figures sometimes incomplete with limbs or heads missing, frozen mid gesture, seemingly swaying or dancing to unheard music or engaging in some sinister ritual. They are unsettling, eluding comprehension. His portraits—if they can be called such—tell nothing of the sitter. Borremans uses the language of portraiture to draw in the viewer but then subverts our expectations and understanding of the works. The painted figure is beside the point, more absent than present, an object to be posed and deciphered like a riddle, rather than a subject with a story.

Borremans' painted figures are Beckettian actors without a script, posed theatrically, resembling Edouard Manet's The Dead Toreador (1864), where a female figure lies on the ground cocooned and obscured in a red polygonal cardboard cylinder as if lying on a stage. They are untethered, directionless, forever waiting in a non-place, forever forced to repeat pointless actions that seem to have no beginning or no end. Some of Borremans' paintings, such as Automat (I) (2008), feature figures with truncated torsos or dismembered limbs, further suggesting that these are figures trapped by a pervading sense of futility. Borremans has said '... it is a conviction of mine ... that the human being is a victim of his situation and is not free'. Even the gestures and postures of the figures, with slouched shoulders and downcast faces, seem to indicate resignation, as if they had long ago accustomed themselves to the purgatory of their existence. There is an atmosphere of brewing tension and anxiety with an undertow of horror tugging away beneath the surface in his paintings: with his paintbrush Borremans brings to life a cargo of existentialism.

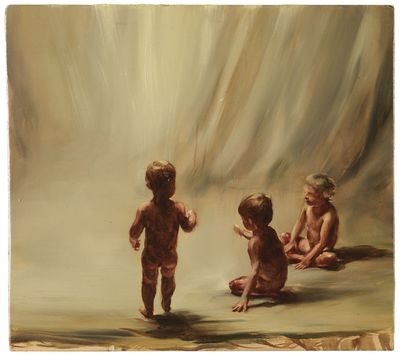

The unsettling intensity in Borremans' works is taken further in his latest series 'Fire from the Sun' (2017), seen at David Zwirner. These intimate yet large-scale paintings feature cherubic, golden-haired toddlers playing and wreaking havoc against a draped studio background. On cursory glance, they could be capturing a fun-filled photo shoot of children. The works are almost sickeningly saccharine. Several depict toddlers covered in a dark liquid that could be mistaken for jam or Nutella. But it's not jam, and these are not anarchic toddlers on a sugar high. Further along, another painting reveals a trio of bloody toddlers feasting on flesh and playing with a severed head and adult limb; in another, several appear to be roasting a limb in the background, like resourceful and particularly skilled cannibals (they learn so young these days), while another two in the foreground appear to be weighing up the merits of a severed adult hand.

Like Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness, based on the author's journey to the Congo in 1890 during King Leopold II of Belgium's brutal rule, which saw the death of millions of Congolese, Borremans conveys the horror, brutality and darkness of the human soul: the unrestrained Id. If Borremans' previous paintings were perhaps too subtle, as he suggests, 'Fire from the Sun' portrays humanity consuming itself. They are paintings that penetrate deeper and deeper into the heart of darkness.

DdYou are exhibiting at Artspace as part of the Biennale of Sydney (BoS) from March to June. What is your approach?

MBI want to do an experiment there. I want to show part of my thought process in the evolution of my work. I will be showing a lot of stuff that I have in drawers and that has been significant for me. Some are old pictures I've collected from here and there, even from the internet, and I've them printed out—things that have been influential in forming my vocabulary—and a lot of drawings, unfinished drawings from my personal archive, shown in vitrines. There will also be scale models—little sculptures, ideas for sculptures. Sculpture is a hobby for me. Nobody is waiting for it and I like that. I am including a couple of film works and spaceships that I have designed.

These are all things that are influential for my visual language, which I do on the side but are important for me. I will show part of my artistic repertoire I suppose—what's in my head and has formed me—I think it will be interesting for the show.

DdYes, you have film, video, drawings. How do different media all feed in to each other?

MBYou will be able to see the connection. There will be very few paintings, just a couple. There will be sculptural works—a sculptural installation. There is a bronze spaceship I designed [laughs]. Crazy things.

DdYou've worked on a number of films in the past. How does your approach to film differ from that to painting?

MBI've done maybe six or seven short loop films. They come out of necessity. They derive more from sculpture than from painting. Of course, the subject is sometimes analogous to paintings, but it is just an urge to see how sculpture could look if it wasn't static; if it could move somehow, even if it doesn't really move. If you film something that is standing still, there is still an aspect of movement to it. Another problem I have with sculpture is that it's very physical; it's very concrete, it's in space and you can touch it. Painting is a window on another world, which you can enter, and I find this fascinating. That is why if I show sculptures it's in a vitrine—you cannot touch them. I even put dust on them. Normally the vitrine serves to prevent dust from getting on the work, but I do the opposite. That's what I have been experimenting with for Sydney.

Weight (2006), the second film I made of the girl turning, was based on an idea for a sculpture that would continually turn around and it would be alive. I had a whole mechanical sculpture made, but it was just ridiculous. Then I thought I have to do the same with a living girl. [The work shows what appears to be live footage of a legless girl; the top half of her body rotating slowly on a table.] That's how that came about. Most of the film works have to do with sculpture ideas, but they are experiments to me.

DdAre the films like moving paintings?

MBYeah, one of them. The Storm (2006) is a one-minute loop where you see three figures just sitting there. They were three guys who were acting in another film of mine but here they are just resting. They were young guys and they'd been out the night before on drugs and they were just sitting there. I saw them there by accident and told the cameraman 'Please film this!'. And it was much better than the film I was working on. I threw away the other film and kept this.

DdDid the guys know about it?

MB[Laughter] They didn't know anything. But I paid them.

DdIt sounds quite Lynchian [the film director David Lynch].

MBYes, that work was a bit Lynchian and it feels like a large painting, as you said, because they're wearing these white satin suits and the guys are black. It's really one of my favourite film works and is presented as a large projection. There is a newer film, The Bread (2012), of a girl eating bread. She is like a Madonna. I made this work to be presented in a cathedral in Belgium. There is of course a connection with the Catholic mass where you eat the bread, the body of Jesus. You have this young virgin eating the body of Jesus. Nobody saw it as a provocation, but to me it was a provocation. It looks so sweet that nobody was aware of it. These are the two film works I am showing at BoS.

DdThis idea of ritual filters down into your work, especially in the 'Black Mould' (2015) and 'Fire from the Sun' series.

MBThere is an analogy with rituals, but it's never really clear, it's not specified. That's important for me in my work, to not define anything, to allow for different analogies so everybody can relate to it in a different way.

DdYou ascribe a lot of importance to the viewer in completing the narrative.

MBYes, that's part of the communication you do as an artist. It's not finished. It only exists in the eye of the beholder.

DdInitially you were trained as an etcher. What prompted you to shift your focus to painting? What allure does painting hold for you?

MBIt was overnight. It was like an epiphany. All of a sudden I knew I had to paint. One sudden moment it just came to me that I just had to paint.

DdWhat was the first thing you painted?

MBI did a lot of practice. My first painting was abstract almost. I wanted to master it, to find my own language in this material that I never thought I could master.

DdThere is a dialogue in your paintings with artists such as Goya, Velázquez and Manet, for example. What is it about these artists that appeals to you?

MBThese painters and their technique, they're most suitable for me and my temperament, because the way you paint has to do with attitude and temperament. That's why painting continues to remain an interesting medium, because every artist can find his own language in this medium. It's like a musical instrument. Everybody has to find their own style of playing. And it took me a while to get there. It's still an evolution, which is interesting of course, because I don't know how my work will look in ten years or so. It's an adventure.

DdI'm interested in the evolution of these paintings. How did they come about?

MBI got tired of my work. I felt a need to make my work more poignant, to give it more gravitas, to make it more relevant, even. It's been an evolution since then, and I am trying to seek ways to do this, and this is one of my attempts. Also, I thought my previous work was often misinterpreted. I was thinking maybe it has to do with me, maybe I'm not accurate enough with what I am trying to show. Maybe I have to accentuate some aspects a bit more, like this undertone of violence you mention, because it's there in a lot of my older work too, but it was maybe too subtle. So, my mistake, I guess. I have to do better.

DdI recall you once said that people either loved or were repelled by your work because of this beautiful painterly quality. That the main focus seemed to be how the painting was painted, and everything else got overlooked.

MBYes, that got too much attention and I didn't like it. For me, it was about the effect that the image provokes and this is more to do with the content than the technique. Of course I like painting when it's beautifully executed—it's very enjoyable to look at. I think I'm trying to find a way to do that—looking for this perfect balance—but it can't just be beautiful because that's pointless. It has to serve another goal: as form has to follow function, technique has to follow content. It has to help the expression and that's what I'm trying to do. Magritte, for example, used very different techniques—he came from a background of painting advertisements—he used a technique to serve conceptual work and it was a perfect technique for him, for what he was trying to say, and I'm trying to do it the same way throughout my practice. Perhaps in two years I will look back and think, oh I can do better. I hope so. I always want to improve ... All my favourite painters have grown better and more interesting with age.

DdOut of curiosity, do you still paint in the bunny suit?

MBI did once, but now I want to dress up like a policewoman. I'm looking for a nice uniform to wear to see if it will influence what I'm painting [laughs].

DdDid being dressed as a bunny influence how you painted?

MBNo, it was just very cold in the studio.—[O]