Derek Fordjour's Vibrant Interactions

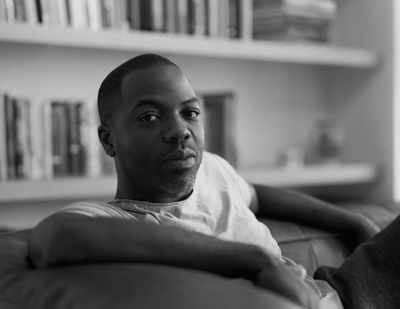

Derek Fordjour. Courtesy the artist.

Derek Fordjour. Courtesy the artist.

A rising star in recent years, Derek Fordjour was certainly not an overnight success, but once he finally found his voice, the art world started paying attention, with that interest continuing to grow.

A painter, sculptor, and installation artist who was born and raised in Memphis, Fordjour was in and out of college for nearly a decade, first receiving a Bachelor's degree from Morehouse College in 2001. He earned a Master's in Art Education from Harvard University the following year, but didn't get back to pursuing a higher degree in painting until 2014, when he began an M.F.A at Hunter College and eventually finished school there in 2016.

Best known for his complex, intriguingly crafted figurative works concerned with issues of race, identity, and inequality, Fordjour credits Nari Ward and Carrie Moyer with guiding him through grad school, but it was a chance encounter with Kerry James Marshall some years earlier that helped him get his artistic career moving in the right direction. His first big break came when he was still in his initial year at Hunter with a solo show in Bushwick, which was followed by one-person outings in London, Los Angeles, and Turin.

A 2016 artist residency at the Sugar Hill Museum ended with a solo that included his first art installation (Parade, 27 July 2017–11 February 2018), which garnered critical praise from the New York press, and was quickly followed by a commission from the Whitney Museum of American Art to produce a large-scale painting for its Billboard Project, with the museum acquiring the mixed-media painting for its permanent collection.

The artist was on his way to greater opportunities, with solos at Night Gallery in Los Angeles (JRRNNYS, 2 February–2 March 2019), Josh Lilley in London (The House Always Wins, 4 October–16 November 2019), and Petzel Gallery in New York (SELF MUST DIE, 12 November–19 December 2020) providing space for his captivating concepts to blossom. In early 2021, the artist joined David Kordansky Gallery in Los Angeles, where he will hold his first solo exhibition with them in spring 2022.

Through these opportunities, Fordjour developed a complex process of painting. After applying colour to canvas, he glues on painted cardboard tiles and then wraps the entire surface in layers of newspaper, which he partially scrapes away. Adding another layer of newspaper cut into circles, strips, and squares, he dissects it while drawing with charcoal and painting on the surface. Creating a lively, layered field of figures and forms, his paintings convey carnivalesque characters, popular performers, and stylised sport subjects in an animated arrangement of colour and texture.

The allegorical relationship between the performers and art provides a philosophical context for his thinking, with the gamification of social structures and the inherent vulnerability of the individual becoming recurring themes in the artist's work. The six paintings in his exhibition Gestalt (15 May–2 July 2021) at Shanghai's Pond Society continue the investigation of these concepts, while also launching a new exploration of the gestalt, both as content and as form.

PLHow did you develop your concepts for gamification of social structures and the inherent vulnerability of the individual, which you then began to explore and still continue to investigate in your work?

DFI was looking at cultural materials and found myself obsessing over athletes, even though I wasn't interested in the particular sport or celebrity. When that intersected with my own self-work, I realised that I wasn't comfortable with vulnerability.

I would never say that I was overwhelmed, nor would I publicly admit to failure. I had a false notion of self-presentation. When I finally came to realise the vulnerability that made me uncomfortable was also my power, it made sense as to why I was looking at athletes. They're vulnerable to the outcome of the game.

There will be a winner. There will be a loser. Something can go wrong. I started to explore that allegorical relationship with society and race and power and economics. It became the framework for which I can plug in all of the things that interest me.

PLHow did you devise such a complex painting process?

DFDuring tough times I worked with newspaper, which is a fragile material, but the joy of drawing on such a surface with vine charcoal freed me from the oppression of easel painting. I enjoyed how liberating it was.

It allowed me to start cutting, but then I had this hollow object that needed more support. Experimenting with ways to create more support ended up creating a new kind of surface. Now I react to something in every painting.

I never just deal with the whiteness of the canvas. I'm always reacting to an embedded history in the work. There are about ten layers on every surface. It has become quite a process, even though it's not something I purposely set out to do.

PLI know that you use the Financial Times for its pink colour, but does its content play into your ideas of commodification and racial inequities?

DFYes, and you're probably the first person to make that connection. I made that decision when I was thinking about personal value and perceived value. The Financial Times is making an effort to differentiate itself from the pool of other newsprint with its distinctive colour. The idea of individuation—the desire to distinguish oneself in the face of being stereotyped or grouped—has a tension that I identify with.

A lot of the colours in my work are situated next to each other. The eye does the work of putting them together.

PLWhat's your theory of optical colour mixing?

DFAgain, as with so many things in my life, it was born out of failure. I'm a really impatient painter, but making an oil painting on canvas requires a patience for colour mixing. The way that I currently work allows me to break the rules and still achieve the optical richness that I want.

By working through various surfaces and allowing space for interaction, I can achieve a vibrancy. A lot of the colours in my work are situated next to each other. The eye does the work of putting them together.

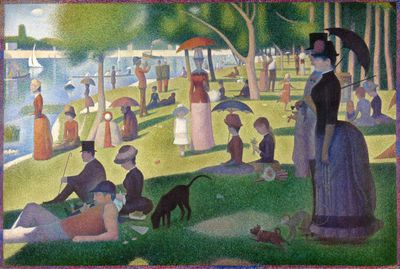

PLThe end result reminds me of pointillism, particularly Georges Seurat's A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte (1884–1886), which depicts figures flatly displayed in a staged scenario. Are modernist painters like Seurat an influence?

DFYes. Not just Seurat, but also Pierre Bonnard, who had an amazing dry-brush technique, which is very rough, almost as though there is no medium in the paint.

I also like William H. Johnson, who makes ham-fisted, solid choices of colour, which work almost melodically. They have a saturation and proximity to each other that's almost a puzzle-like fit, which I love. I'm also inspired by Romare Bearden's collages and the pointillist patchwork in David Hockney's Los Angeles landscapes. I try to bring all of those things to bare in what I'm doing.

PLWhat's your philosophy of autonomy and control?

DFIt's an expression of my own anxiety. As an artist operating inside an ecosystem that's profit-driven, I think about my vulnerability. Where is my agency there? If I'm relying on other entities to arrive at value that sustain me, I have to ask that question.

As a Black person in America, it's a conversation that we are all privy to and think about. As a citizen in a capitalist environment, you cannot help but consider your relationship to capital and economics. I'm interested in these relationships to power.

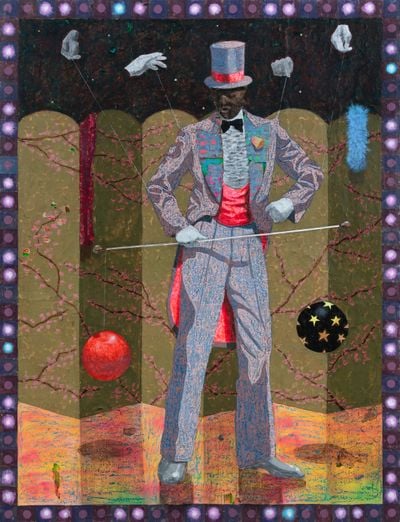

PLLet's talk about the paintings in the show, starting with Capital & Labour (2021), which depicts a well-dressed man and a showgirl. What's the message being conveyed through these characters?

DFI'm not sure that there's a message, but I am interested in how the viewer adds up the elements in the painting and the narrative they project onto that stage. The meaning of the work is really up to the viewer.

PLDoes the painting Collection of Evidentiary Facts (2021), which presents a room full of trophies and honours, visually express your theory of meritocracy?

DFYes. There is no reason why I need three degrees to make a painting. What is that about? A lot of it is the hope that these degrees will add up to some greater value, which might inoculate me from the vicissitudes of my demography. That's really what's happening.

Unfortunately, at a traffic stop, the police don't ask for my degrees. I can't show them to a hostess when I'm asking to be seated at a restaurant. That futility is something that interests me. It's what drove me to make this painting.

I'm also interested in the universality of achievement, the artefacts of achievement, and the American ethos around winning. It's an opportunity to make reconsiderations about what that is. It starts with me, but I'm interested in how my experience can amplify these other more universal concerns that are possible from the paintings, too.

PLDownstage Busker (2021), with a performer being controlled by strings, seems to address the ideas of autonomy and control, but is it also addressing the concept of performing competency, of looking like you know what you're doing, of playing the part?

DFRight, I wouldn't disagree with that interpretation at all. The subject of the painting is probably an emotion. It's not exactly portraiture. It's really more about a feeling. If I had to create a self-portrait—not of my physical being, but of my emotional state—it might look like this painting.

PLThis show, however, is about the theory of gestalt and, though all three of the paintings we just discussed express different principles of that theory, Full Step Triad and Thalassic Quintet (both 2021), which show three drum majors in the former, and five synchronised swimmers in the latter, present patterns and structures in even more obvious ways. What are you saying with these paintings?

DFI'm interested in how gestalt can address both form and content. There's a very real formal investment in how I build compositions and I think there's a real delight to it. As painters, we're always interested in the formal properties of a picture; however, what becomes interesting is how these compositional arrangements can also carry context.

The transformative power of world-making in art is something that I want to deliver to people.

I'm reading a book titled Minor Feelings (2020) by Cathy Park Hong, which is written from an Asian American perspective, about power, autonomy, and assimilation, and it resonates with me. I ponder those things as they pertain to the principles of gestalt.

When you think about proximity, repetition, and the challenges of a marginalised person to individuate themselves from a group, there's this wonderful alignment between my formal concerns and the conceptual ones, particularly through bringing this conversation to China right now.

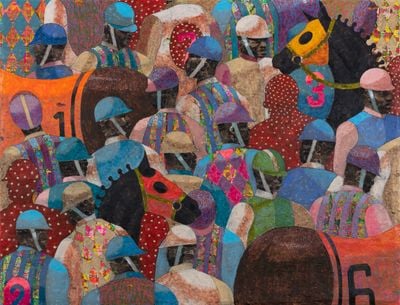

PLThe Second Factor of Production (2021) returns to one of your favourite subjects, jockeys, who are massed together in a sea of colours and patterns. What's the importance of the jockey, both historically in America and in your work?

DFThe painting is a consideration of Black labour, both presently and historically. The Black jockey was born out of slavery. When we had an equestrian-based society, in which it was fashionable for the plantation owner to ride up to the country club on a beautiful horse. It was an enslaved person that maintained that horse. As a direct outgrowth, enslaved people became the first jockeys.

After they were freed, Black jockeys were able to win purses and achieve a level of wealth. Then, around 1905, when Blacks started migrating north and the race riots began, the public appetite for Black jockeys changed. They were extracted from the sport and that absence has remained until today.

I came into the world of art-making at a time when Black artists were viewed as particularly valuable commodity. The presence of the jockey in my work is cathartic for me. It expresses my skepticism of Black moments in America.

PLAlthough this show is centred on painting, sculpture and installation have become an equally powerful part of your practice. How have they helped expand what you do and the thought process behind it?

DFSculpture is wonderfully inspirational because I don't readily regard myself as a sculptor. Going back to the years when painting was so arduous for me, one of the things that I did in my studio to make it a more joyous place was to go to an area to which I had no expectations. Because I was primarily a painter, sculpture had all the joy of discovery and freshness.

Installation is world-making. If I can capture all of your senses, I can make you believe in this other realm. I love artists like William Kentridge or Red Grooms, who can create a whole universe. I forget where I am. I'm engrossed.

The transformative power of world-making in art is something that I want to deliver to people. It's almost like an act of love to say change your realm, come in and leave it all behind... Take a ride.

PLIf you had been able to create an installation for this current show, what might it have been?

DFHah, that's not a fair question. Did I sign an agreement that required me to answer every question you asked? Because if not, I'm going to exercise my right to pass on this one.

I wanted to think of this exhibition solely as a painting show. I wanted the strength of the paintings to do their thing, so I didn't even allow myself to consider other media. —[O]