William Kentridge is a South African artist known for his animated films and drawings, as well as sculpture, tapestry, and works in other mediums that examine the struggles and emotions of post-Apartheid South Africa.

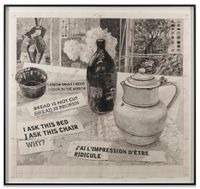

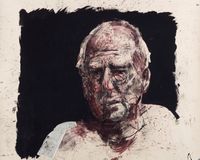

Read MoreOften using inexpensive, commonplace materials such as charcoal, pastels, and paper, William Kentridge makes drawings of human figures and landscapes in an expressionist manner. The dramatic stylisation of Kentridge's work reflects his inspiration from satire and artists including Honoré Daumier, Francisco de Goya, and William Hogarth.

Kentridge's work often addresses violence and trauma, and the processes of commemoration and forgetting. In his 2018 conversation with Ocula Magazine, the artist said that, for him, a close relationship exists between the human body and the landscape, 'both in the sense of the work that is done on the landscape, from its defacement and construction—a bit like the changes that can be affected on a person.'

An integral part of William Kentridge's practice is the emphasis on process. For the animated short film Felix in Exile (1994), for example, he made large-scale charcoal drawings, erased parts of them, and made changes. Kentridge photographs each alteration, later sequencing the images into an animation. Throughout the film, the traces of earlier drawings add weight and a sense of traumatic loss.

Felix in Exile belongs to 'Drawings for Projection' (1989–2003), a series of films made from drawings that navigates South Africa in the years leading up to and following the end of Apartheid. Another film in the series, History of the Main Complaint (1996) was made similarly by drawing and redrawing 21 artworks, and follows the story of a white property-developing magnate who is violently beaten and hospitalised.

Though well-established in South Africa, William Kentridge's work was slow to receive international attention until 1999, when his solo exhibition William Kentridge travelled to Museu d'Art Contemporani de Barcelona; Serpentine Gallery, London; and Kunstverein München, Munich, among others.

Ocula | 2021