Gu Wenda

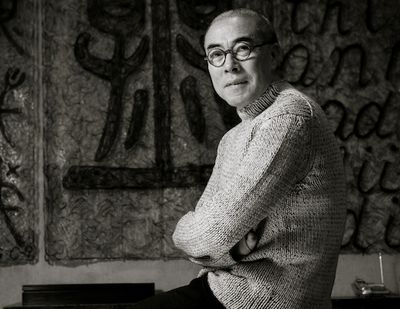

Gu Wenda is best known for his extraordinary installations comprising human bodily substances – powdered placenta, blood and hair. Born in Shanghai, Gu studied at the Shanghai School of Arts and Crafts and then the Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts in Hangzhou. The artist’s early training in traditional Chinese painting laid the foundation for his provocative later work. This often involves the manipulation of Chinese calligraphy using the extraordinary range of media that his practice has come to be associated with.

Immediately after completing his studies in the 1980s, Gu began the first of a series of projects centered on the invention of meaningless, false Chinese ideograms, depicted as if they were truly old and traditional. One exhibition, held in Xi'an in 1986 featuring paintings of fake ideograms on a massive scale, was shut down by the authorities who, being unable to read it, assumed it carried a subversive message. The exhibition was later allowed to re-open on the condition that only professional artists could attend. Although such works placed Gu Wenda as a major figure in the ‘85 Movement’ in China, like many of his artistic compatriots he left China for the West and now permanently resides in New York.

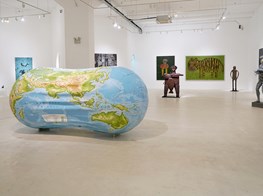

His own experience of crossing borders and living a life outside of his own home country possibly inspired a fascination with the permeability of cultural boundaries. His most ambitious project, United Nations

, consists of installations at sites around the world; and involves the use of human hair to create walls and screens upon which the artist uses additional hair to form both comprehensible and nonsensical characters, letters and scripts. Using hair from over four million people, the work draws attention to the tenuous nature of cultural divisions, and presents a utopian possibility of humanity united. The work also presents a manipulation of language and exploration and re-interpretation of Chinese traditional modes of expression, seen in other works by the artist such as Forest of Stone Steles – Retranslation & Rewriting Tang Poetry, in which the artist has manipulated, juxtaposed and layered translations and re-translations of poetry from the Tang Dynasty.

During Art Stage Singapore, Gajah Gallery is working with Gu Wenda to present one of the artist’s newest large scale installations, The Yanhuang Landscape (2012) – a work that evokes the Chinese landscape tradition using hair–made black ink on green paper – uniting themes from Gu’s earlier works. In the wake of the opening of The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Ink Art: Past as Present in Contemporary China – a critically acclaimed exhibition that has been hailed as pivotal in the understanding of contemporary ink and which includes a major work by Gu Wenda and in the lead up to the opening of Art Stage, Ocula invited Tiffany Beres, curator of the Gajah Gallery’s exhibition to interview Gu Wenda about contemporary ink, and his latest work.

You are known as one of the founders of conceptual ink art. Can you tell us about a little bit more about your ideas on contemporary ink art?

Contemporary ink art dates back to the early 1980s, during post war era shaped by Deng Xiaoping’s reforms, and yet today it is still in an odd position. Contemporary ink art has not necessarily departed from traditional Chinese painting (guohua) and is not necessarily contemporary; it think it is somewhere in the middle.

I believe I am lucky because my work has always been affiliated with contemporary ink. I come from a background of traditional landscape painting and calligraphy, but as a contemporary art figure, I feel I need to create a new art identity with ink. Many contemporary artists in China are turning back to ink art because after 30 years they no longer want to work from imported Western ideas; they are just beginning to reflect on their own history and identity. I think this is why ink art is becoming something of a trend, even overseas.

Personally, I believe that all art media has a heritage that we must consider. Oil painting was perfected during the Renaissance hundreds of years ago, but it continues to be a major painting media of contemporary visual arts. In the same way, ink needs to be appreciated in terms of its own history. Ink art is different in terms of aesthetics, materials and techniques, but why can’t it have a conversation on an equal-level with oil painting? Each culture, of course, has its own artistic traditions, but I believe that ink art has an unprecedented opportunity to become an important global media. Some people doubt that ink media can be transported to other places in the world, but I think this will come with progress and transformation.

What kinds of transformations have taken place in your own ink art practice?

Before I left China (in 1987), I established my ink art practice in installation and performance; I used characters without any meaning and political icons taken from propaganda of the times and inserted them into my ink painting work on a large-scale. For me, this was a kind of double power: these ink works were both scholarly and socialist—they represented the two major schools of thought and authority in China at the time.

At that point, I was still in Hangzhou, which you might say was the center of this earthquake in traditional Chinese painting, since there was so much going on. It was because of this environment that I began producing contemporary ink art, not the other way around. I feel like it was the time that produced me—and I belong to that moment.

Perhaps it was the dynamism of the period that inspired me to consider installations and performance. Even today, when I finish any kind of new work, I always feel it is incomplete until it is displayed in public. Contemporary art needs be viewed by different audiences before it can really be judged. Art is not meant for just the elite, the more people who see it, the more complete it is—that is why my works, even my ink paintings, have, from the beginning, had this element of audience participation.

Although not directly tied to ink art, this idea of audience participation is also directly related to my United Nations installation—a project where I made all 188 national flags of the world using hair collected from these countries. By now the United Nations project is in its 20th anniversary, and I have had more than 20 large-scale installations of United Nations shown around the world. It is hard to imagine, but the hair of than 4 million people have contributed to this project—to me this kind of scale is essential, it is unprecedented. Whatever medium I work with, ink painting or installation, I feel I have to reach the impossible.

On that note, can you tell me about your previous project for the grand opening of the Singapore Esplanade in 2002?

In 2002 the Indonesian art patron Valentine Willie was the acting curator for the opening of the Esplanade, and he selected my United Nations work for the main lobby space. I had just completed the complete series of flags, and I was eager to showcase the work. To me, United Nations is a kind of unification; people from all over the world have participated directly in its creation. It showcases the relationships between countries—each country has a distinctive identity, and yet they are all unified.

At the time, the work had very mixed reactions. Singapore, if I may say, is rather conservative: the country is very mainstream and modern, but perhaps in art taste they are rather traditional. This work was challenging for the audience—the majority of people who came to the show never expected that the lobby of their new theater would be filled with hair!

For me, I believe that important contemporary art must itself always be pioneering, it should raise new and challenging issues. The United Nations got good exposure because it was so different from traditional art. I think it made a big splash.

How does your new work, Yanhuang DNA Landscape, relate to your previous work?

The Yanhuang DNA Landscape is a new and special project that continues to play upon some of the ideas in my earlier work. Similar to United Nations, my new installation is also made with hair. You see, for me, hair represents a person’s identity because it contains our DNA. I try to use human hair to reinvent ink, so that when you paint with this human-hair ink you are literally painting with DNA. It is a very interesting concept because this is not traditional ink; it is like painting with markers of ourselves.

As a contemporary artist, I am of course interested in doing something new. Today it is difficult to escape from Western impressionism, realism, and abstraction—concepts that are very different from my own Chinese art tradition. Ink painting is very different from oil painting. Ink is an object that goes back to the heritage of China. As you know, I have always been interested in trying to thoroughly rediscover the identity of ink.

In traditional Chinese medicine, hair powder is also used as a medicine for stress. I find it an interesting conceptual idea that we can now take hair powder and transform it into ink that can then be used as a cure for our cultural anxieties.

To carry the ink, I also invented green tea paper. Green tea is also a potent symbol of Eastern tradition, and in its own way, tea is also a marker or carrier of culture. I worked with a well-known factory in China that used traditional papermaking methods to create 30 thousand sheets of paper using over 4000 lbs of green tea leaves.

From 1999 to 2002, I finished those two “inventions,” which I call Ink Alchemy and Paper Alchemy.

Why did it take so many years for you to finally use the products of your Ink Alchemy and Paper Alchemy to create new work?

Yes, for a long time I debated what format to use for my DNA ink and green tea paper. Using these new ink and paper media, I knew I could not just repeat traditional painting ideas. In the end, I decided I wanted to create a very simple landscape—one with no activity, no signs of life or habitation. The Yanhuang DNA Landscape is very minimal; there is only a basic form of mountains because I wanted to capture a new horizon.

This landscape is ink painting, but it is not traditional. This century has been named as the biological century because science focuses on DNA, genetics, and the human body. Instead of creating work that is outside of the human condition, I believe we can literally use bodily materials to create works that speak to our culture and times. Good art always tries to present the era that the artist lives in so it can become iconic and symbolic of our times.

This is the first time you have shown Yanhuang DNA Landscape outside of China. Why bring this work to Singapore?

I feel like I have a special relationship with Singapore, and it’s a story that’s only just beginning. The Chinese community in Singapore is very strong, and ever since China’s Open Door Policy, there has been increasing ties between the two countries in terms of investment, politics, society, culture, etc. Exposing my work Yanhuang DNA Landscape in Singapore now is not a coincidence—the historical background and Chinese cultural ties of the work make it highly significant. Of course, Singapore has its own cultural identity. Whenever I go back to Singapore, I realize it has become a kind of melting pot. However, the majority of the local population has Chinese roots or some exposure to Chinese culture. For me, I thought ArtStage was a great opportunity to showcase this work to a wider audience.

It is only fitting to bring Yanhuang to this unique artistic and cultural location, and I would like to thank Gajah Gallery for providing the chance to display my installation in Singapore. And of course, I would also like to thank the curator for putting it all together. — [O]