Jens Faurschou

When American artist Robert Rauschenberg

opened his first and last gallery exhibition in China, (he died shortly thereafter), it was with Galleri Faurschou in Beijing, owned by Danish collectors Jens Faurschou, and his now former wife, Luise. Jens Faurschou took Ai Weiwei to see the show and the acclaimed Chinese artist, impressed by both the exhibition and the gallery’s space, agreed to show with Galleri Faurschou, too; so began a long-term relationship which currently finds form in Ai Weiwei: Ruptures showing at the Faurschou Foundation in Copenhagen until 22 December 2015.

Jens and Luise founded the Faurschou Foundation in 2011 after twenty-five years in the gallery business, choosing to close both their Copenhagen and Beijing commercial gallery spaces, and setting up the privately owned art institution in both cities instead. The Foundation, which also has an exceptional collection, has gone on to show exhibitions involving some of the world’s most important artists, including Cai Guo-Qiang, Louise Bourgeois, Shirin Neshat, Gabriel Orozco and Chen Zhen. Most recently, in addition to showing Ai Weiwei in Copenhagen, the Foundation has shown Bjarne Melgaard in Beijing and Liu Xiaodong in Venice.

In this Ocula Conversation, Jens Faurschou discusses how he first became interested in art, Rauschenberg and Ai Weiwei, opening a gallery space in Beijing, the work by Bruce Nauman he missed out on, and why he thinks Liu Xioadong is one of the most important Chinese artists working today.

Can you remember the first piece of art that had an impact on you?

Yes. It was at Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, and I was probably fifteen or sixteen years old, and it was a work by Yves Klein. It was a triptych: blue, gold and red. It was a huge work, and one of his most important works. I was completely shocked that what it was could be called ‘art’.

I continued thinking about this work. So it had some impact on me. Now, it is the work I always go back to see, and I still love it today. It moved some borders for me, so it must be art.

I am not from Copenhagen; I was born on an island in the middle of Denmark, in a smaller city. I was not used to modern or contemporary art. So to come to Copenhagen and go to Louisiana Museum of Modern Art and see that work—it changed a lot for me.

You went to a business school and dreamed of being a CEO, but a job at a library of fine arts led you towards pursuing an art world career?

I went to the Copenhagen Business School—and while I did start a gallery while I was a student there—in going to business school my dream was to be the head of one of the big Danish companies. However, I became interested in art, and I have actually never been employed by anyone else than myself after graduating from the business school.

Before we opened the gallery, when I was still a student, I worked at an art library (and not at the Royal Danish Academy for Fine Arts library as it has been misquoted in previous articles). It was a place where you could go and borrow paintings. People could become members, and exchange their artworks.

Does this library still exist?

Yes, it does. They have a little bus that goes around the country and they go and visit companies, which are also members, and they exchange the works, and the bus continues on.

I liked working there. There were a lot of young artists who gave their works to the library, so because of this, I met a lot of the young artists in Copenhagen.

Faurschou Foundation, Copenhagen, 2012. Photo by Anders Sune Berg, © Faurschou Foundation

You then opened a gallery in Copenhagen, and subsequently Beijing. I am jumping ahead, but am intrigued to know what took you to Beijing because when you opened the gallery in Beijing, it was very much in the early days of the West becoming aware of Chinese art.

Our gallery in Copenhagen had grown. In Copenhagen, we were in the same address (but two spaces) for twenty-one years, and the inventory had grown.

I felt that it was time to open a space abroad, and my immediate thought was to do it in New York, and another thought was Berlin. But then by co-incidence I had to go to China. At this time China to my mind—this was in 2006—felt so far away. An artist that I worked with was invited for an exhibition there, and I promised to join him there.

I was completely shocked when I arrived in China: shocked about how developed it was. You know in 2006, there was nothing [in the news] about China, but today when you open the newspapers, it is all about China. It has changed in such a short time, but when I went there in 2006, I knew so little about the current developments, and I was shocked about what was going on there.

So I went up to Beijing with this artist, and we visited 798, and I fell in love with it. It was so nice. I saw that there were a lot of great galleries showing Chinese artists, and there were some galleries showing foreign artists, but nobody was showing the great Western artists.

So instead of opening a gallery in New York (where we would be just another gallery), I thought: let’s do it in Beijing where we can make a difference. Beijing also opened up the opportunity to show works by artists who I loved, but whose works I otherwise possibly couldn’t show elsewhere because of their main gallery obligations. I felt that in Beijing we could really make a difference.

Exhibition view of exhibition Bjarne Melgaard: Bitter Angel, Faurschou Foundation, Beijing, 2015. Photo by Jonathan Leijonhufvud, © Faurschou Foundation

So what was your first show in Beijing?

It was Robert Rauschenberg, and he was still alive. It was his last gallery show. Sadly, during this show, he died. And I was so grateful he had said yes to this exhibition.

Rauschenberg of course had a huge influence on many Chinese artists.

Yes, absolutely. And that was one of two reasons for doing it. For me Rauschenberg is probably one of the most important artists of the 20th century. We had done things for him in Denmark from the time when we started the gallery there. There was a long-term commitment from us to Rauschenberg.

How did you originally meet Rauschenberg, and start working with him?

I first became interested in his work via a collector who had started collecting Rauschenberg’s works in the early 1960s. He spoke to me about Rauschenberg, and his excitement made me interested. Then I did some sales involving Rauschenberg’s works: we bought some and we sold some. Then Rauschenberg had a show with [Ernst] Beyeler at his gallery in Basel. I had become good friends with Beyeler through our dealings—we did some deals together—and I was down in Switzerland visiting him and he told me about the Rauschenberg show he was doing, and he asked if I would like to do it in Copenhagen, and I said “Yes”. My space was much smaller than his, and I was talking to a museum friend saying how much I wanted to do a bigger show with him, and he ended up with a museum show, and that was my first big commitment to Rauschenberg—that was in 1994.

Since then, we have been involved in many of his shows.

You have given an anecdote before about hunting down a work by Rauschenberg—a work you became obsessed by. Would you mind please re-telling that story now?

It was in 2003, and I went to Rauschenberg’s studio at Lafayette Street and it was with his curator, David White. New paintings from his studio in Florida had arrived. We were there to choose works for a show in Copenhagen and to purchase some. We had been around seeing these new works, which were absolutely great—they were really good.

And David said to me: “Come with me, I just have to show you something”, and this work, Mirthday Man came in. And I was just amazed. I said: “How much?” And he said: “Oh no, no. It isn’t for sale. I just wanted to show it to you”. But after seeing that work, I couldn’t focus on all the other paintings.

What was it about that particular Rauschenberg work that drew you to it?

It is very difficult to explain why a work is good. But it is something that you just know straight away. It is there. I cannot put it in words why.

Then I wrote to Rauschenberg. I sent him a fax about it. And an answer came back: “I am sorry. It is not for sale”. It was his own painting. He had painted it for himself for his 72nd birthday. It contains his X-Ray portrait (which he did in 1967), and he had included that within the painting. It is the only painting that has it. (He originally did the X-Ray portrait for a print in 1967). Around it, there are all the images he looks back to with pleasure. So I got this ‘No’ from him, and I thought ok, but I tried again, [laughs] and I gave more good reasons why I should have this painting. And I got a ‘No’ again, [laughs] and this happened five times. I wrote to Rauschenberg five times, and five times I got a ‘no’. When I got the last no, I said: ok, that is it.

Some months went by, and then I got a call. I remember exactly where I was—I was walking on the street—, and I got a call saying that I could have the painting. I was so happy. I still have this painting.

In 2011, you left the gallery world, and you started the Faurschou Foundation. Why did you stop being a gallerist?

The big reason I moved away from being a gallerist is because—and this is after twenty-five years of being a gallerist—I love to do exhibitions, I love to work with artists on exhibitions, and I love to collect, but I actually don’t like to sell.

When you are a gallerist, you work for the artist, and I do like that. When you wake up in the morning, you have a different hat on for a different artist; and when you are out socially and you meet a museum person, you immediately start to talk about your artists, and try to do something for them—I like that. I admire the gallerists in the world who really work for their artists. I don’t like the gallerists who think the artists work for them. It is always about the artist, and you have to do the work for the artist—that is what a gallerist gets paid for.

When I was a gallerist, I sold works, and of course when you make a sale and you have placed a work in a great collection, the best thing is calling the artist and telling them about it. Of course I enjoyed that.

I don’t like to sell works from my own collection, but in reality that is what I lived on while working as a gallerist; the money I made from working with the artists just went back into running the gallery. Every now and then we would sell via the secondary market something we had bought on the primary market—something we had held on for years—and that money was used for the shows and for promoting the artists. That is how we did it, as well as ongoing buying and selling on the secondary market.

After two decades I realised that we had to open up more spaces around the world if we were to continue; the competition between gallerists is such that you need to offer the artists the opportunity to be shown more or less all over the world. I didn’t want to do that.

And what was your experience of being a gallerist in Beijing like?

I thought that being in Beijing, we would sell a lot of Western art to the Chinese. But we didn’t sell a lot. That has changed now, and many of Chinese collectors are today buying Western art.

But I loved the shows we did. I think the shows we had there offered a type of education for the audience. And doing these shows gave me a lot of access to all kinds of artists, including great Chinese artists. So the model worked. We were still able to buy great pieces.

Ai Weiwei and Jens Faurschou, 2014. Photo from personal archives

Who is the first Chinese artist you collected?

Ai Weiwei. And we became good friends over time.

Can you remember the first work you saw by him and your impression?

It was at Documenta. Then in 2006, I went straight to meet him.

I wanted him to see our space because we had started to renovate it. He said: “I don’t need to go to 798. I know what it is like there.” And then when we opened the space in 2007, and we had the Rauschenberg exhibition, I was visiting China, and at the time our space was, and still is, a very beautiful space. I went to him and we had a meeting, and I said again: “You really have to come and see this space, and you need to see the Rauschenberg exhibition.” And he loves Rauschenberg, so he said: “Ok, let’s go”. So we went over to our gallery right then and there, and he saw the space and he loved it, and he loved the works. Then we were going back to his studio, and on the way back, because I had of course asked him about doing a show, he just looked at me and said: “So how much commission do you take?” [laughs] And we did a show.

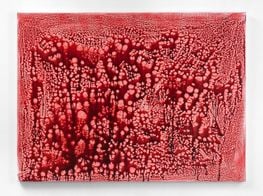

Exhibition view of artwork Straight, Faurschou Foundation, Copenhagen, 2015. Photo by Anders Sune Berg, © Faurschou Foundation

You recently showed an exhibition of his work in Copenhagen. To what extent did Ai Weiwei’s relationship with the Chinese government prevent you from doing a similar show in Beijing?

The authorities in China are not against his artworks. What they became afraid of was his blog—when he collected all these names and got a lot of followers … well … I know they said to him after he was released: “Please just do your artwork”.

His artwork of course contains a lot of critique and is quite political, but it is hidden and it isn’t ‘up in your face’. You know we are showing Straight. It is an amazing piece. You know it, of course. It is the piece with the bars that have been straightened out and relates to the [Sichuan] earthquake. It looks like a ready-made: like he just went and bought the bars and put them up. However, when you hear the story, you realise it is a labour intensive work; each bar (73 tons of steel reinforcement) was collected from the earthquake’s aftermath and hammered and straightened out.

You do have this connection to Duchamp in the work, which you do in most of his work. But also, when you look at it, it is a very heavy work, and it has this masculinity: like the works of Richard Serra. Then you also have this minimalism, like Carl Andre. And he made a landscape form that looks like an earthquake, and when you look at it, well visually, it reminds me of the big landscapes of [Anselm] Keifer. But then when you find out the hidden story behind it, well … there are so many layers to his work. And that is where the critique comes in … it is political … but it is quiet.

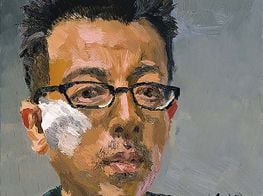

Exhibition view of exhibition Liu Xiaodong: Painting as Shooting, Faurschou Foundation at Fondazione Giorgio Cini, Venice, 2015. Photo by Anders Sune Berg, © Faurschou Foundation

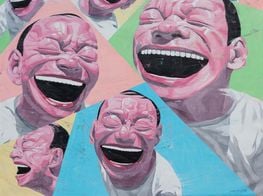

You are also showing works by Liu Xiaodong in Venice. What was it about his work that made you want to show it at Venice?

Like Ai Weiwei, I think Liu Xiaodong is one of the most important Chinese artists today.

Why is that?

For two reasons: he is an extremely talented painter—for me one of the most talented living painters today—and an artist who also needs to have ideas and wants to say something, and his works are actually very political, as well. Every series he makes is like a documentary, which is why we called the show Painting as Shooting. Like a filmmaker who makes a script, he also makes a script for the paintings, and he stages the people who are in them, and the setting. The works are staged and planned before he begins painting. His paintings are like documentaries of China and of what is going on.

One of the paintings from the show that I really like is called Horse Market and in this work you can see the evidence that the artist is out and about painting—because the painting is actually marked with flies.

The Foundation’s collection was originally part of your collection. How do you decide what goes into the collection and what does not?

There are things in the collection that I do not consider as being part of the Foundation. Things I bought from the artists very early on. Things I still have.

What is the most recent work you have collected?

It is a work from Thaddaeus Ropac, a work by Bjarne Melgaard. A completely crazy and wonderful sculpture full of colour and in human size; It is made of human hair. It was there when I walked into the show. And it was “Wow!” when I saw it.

Bjarne Melgaard with Rob Recine, Untitled, Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, Paris, 2015. Photo by Jens Faurschou

What is the most recent dream work you have wanted, but not been able to collect?

The dream work is by Liu Xioadong. In the Venice show there is a series called Hometown Boy and the main painting in that series is in the show. The artist left his hometown, and when he returned there, he had already become a very successful painter, and all of his old friends that he went to school with were there, and he painted them. One of the paintings features a whole group of them sitting there, playing cards. It is so well painted. And I cannot tell you why, but it is his masterpiece.

The day before his show opened, we went and had lunch and I said to him, “So how much?”. And he said: “Jens, I cannot sell my friends. It is the only series I will hold onto my whole life.” I could see straight away, he would never sell.

Exhibition view of exhibition Liu Xiaodong: Painting as Shooting, Faurschou Foundation at Fondazione Giorgio Cini, Venice, 2015. Photo by Anders Sune Berg, © Faurschou Foundation

What are your long-term aspirations for the foundation and collection?

I want the collection to continue to develop. There are so many great things going on. We don’t know what is coming. But we want to continue to collect great pieces. Every once in a while, I have to sell something. Luckily we don’t have to sell everything. Fortunately I have had luck in selling some things, so we don’t have to sell very often. But when we do, we do whatever we need to ensure that the work ends up in a great museum. If it is something I have bought on the secondary market, I don’t feel such great responsibility. I do deal in the secondary market, and I have played and still play that game.

What do you think of the recent record Picasso sale by Christie’s?

Oh it was an amazing sale. Amazing. The fact that there were four people bidding on it surprised me because right from the beginning the estimate was very high. It shows that there is so much money out there to buy art—and this is a good thing—people who pay this much money are probably related to ‘new money’. I don't think it is an old, experienced collector who bought it. I am not sure they would spend that type of money. So this is new money coming into the art market.

The person who sold it—they bought it in the nineties and I was at the auction at that time. The early nineties were very depressing in the art market; there were no buyers. But you could get amazing things for very little money. I think it was in 1998 when there was an auction and it was a huge success, and after that the art market really started to take off. So the buyer of that Picasso, at that time, who has just sold it now … I am sure Christie’s had to have hunted this work down and made an offer and a guarantee too good to refuse. Let’s hope the money they made goes back into the art market. It can be hard to understand that prices can continue to go up, but if I think ten years back, there was still a good market and it was just fine. But now the interest in the art market is so much bigger than then; in every country there are more people interested in art than there ever were before. There are much more people in each country who buy art. The art market has now opened up to Asia, Middle East and South America. So my thinking is [with the Picasso sale], this is new money, and from people who were not buying art before. The amount of people who buy art is still limited, but it is growing.

Who is not in the collection, but who should be?

That is an easy one—a masterpiece by Bruce Nauman.

There was one work at Basel art fair last year that we should have bought: a video installation from 1991/ 2 (around that time). It was so strong and I was so astounded it was there. I did know it was going to be there and we went straight to see it. It was with two galleries, who were working together to sell it: Hauser & Wirth and Zwirner. They had this for sale together and they were asking a huge price and I was a little concerned about the technical side because it is an old work. But it was so strong. I had this feeling we had to buy it. However, I could feel both galleries around us and I felt confident to leave it and I said to one of the curators who works with us, “Let’s sleep on it and then let’s give them an offer tomorrow because I don’t feel there is anyone else going forward with this.” But either late in the evening or early in the morning Anthony d’Offay came by, went in and bought it on the spot.

I should have given them an offer at least. His works are such … I probably won’t get another chance. His best works are almost all in major collections now. It just shows that when you see something really, really great, you cannot hesitate.—[O]