Léuli Eshrāghi on Curating the TarraWarra Biennial

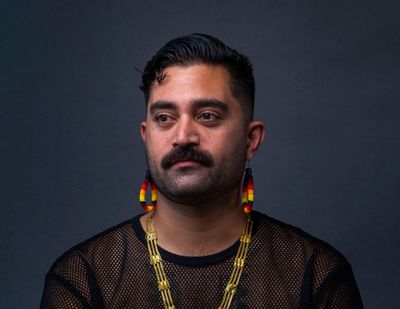

Léuli Eshrāghi (2019). Photo: Rhett Hammerton.

Léuli Eshrāghi (2019). Photo: Rhett Hammerton.

Léuli Eshrāghi has an expansive practice as a curator, writer, researcher, artist, and sometimes poet. Clearly in demand, 2022 saw them appointed as scientific adviser for the exhibition Reclaim the Earth at Palais de Tokyo, Paris; participating in workshops and First Nations-led research projects in Australia and internationally; and exhibiting at Tate Modern, London, as part of the exhibition A Clearing in the Forest: Enmeshed.

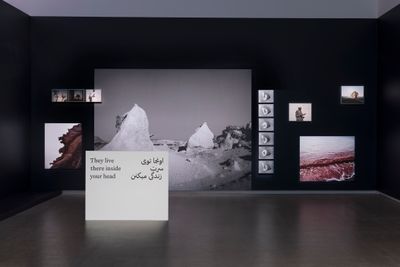

This year, Eshrāghi is the curator of the 8th TarraWarra Biennial at the Tarrawarra Museum of Art, Wurundjeri Country (Melbourne) (1 April–16 July 2023). Since 2006, the event has served as an 'experimental curatorial platform' aiming to identify new trends in contemporary Australian art.

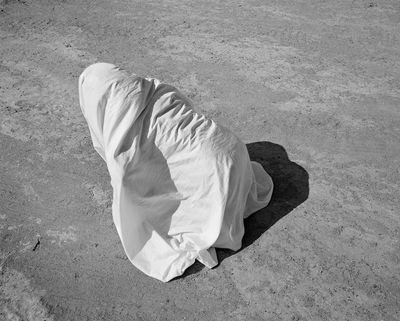

Eshrāghi takes this year's title from the Sāmoan proverb ua usiusi faʻavaʻasavili (the canoe obeys the wind). As they explain, the expression is demonstrative of 'Great Ocean celestial navigation practices' following centuries of European and Asian colonial occupations.

Foregrounding First Nations artists and collectives, the Biennial showcases contemporary artists tied by ancestry or materiality to the many lands and waters constituting Australia, the Great Ocean and largest body of water on this planet (otherwise known as the Pacific Ocean), and the archipelagos and regions from West Asia and lutruwita (Tasmania) to Borneo and Viti Levu (Fiji).

Speaking with writer, curator, and lecturer Rebecca Coates prior to its opening, Eshrāghi discusses their curatorial project, the TarraWarra Biennial. They also discuss Sāmoan proverbs, and how First Nations kinship constellations can help us think differently about exhibition-making.

RCWhere did you grow up and where do you call home?

LEI grew up in Yuwi, Kabi Kabi, Bundjalung, and Yugambeh First Nations territories as well as our ancestral lands in the Sāmoan archipelago before I left home at 17 years old to work in a school in northern Vanuatu. That experience broke and remade me, as have other important places in my life.

I have been on the move between residencies, exhibitions, talks, performances, and visiting kin since February 2022, so I don't have a set home. That said, Naarm [Melbourne] and Apia [Samoa] will always be home to a certain extent, and I feel most myself in Honolulu and Tiohtià:ke/Mooniyang [Montreal].

RCYou describe yourself as a visual artist, writer, curator, and researcher, and hold a PhD in Curatorial Practice from Monash University, Naarm (2018) and a Graduate Certificate in Indigenous Arts Management from the University of Melbourne (2012).

How do these research methodologies contribute to your curatorial practice and processes?

LEThis rigorous academic training taught me attention to detail in terms of Indigenous cultural and intellectual property principles, macro-level scans of the art sectors' issues and opportunities, as well as anchoring curatorial research in expanded notions of time, space, relationality, and responsibility.

I think this platform brings specific responsibilities to the communities I have been mentored and nourished within, across and beyond Australia's shores.

I often return to discussions, analyses, reflections, and speculations from all these periods when approaching perceived and felt problems, such as the recurring erasure of majority world hxstories [more than histories/herstories] and kin constellations from the epistemologies taught and cherished in so-called Australia.

RCMuch of your practice centres on Indigenous art and artists—particularly work across the Pacific region, Southeast Asia, and North America—and ensuring that programming is First Nations and artist-led. Why is this important to you and what does it offer the wider community?

LEAs someone who grew up surrounded by guests from different cultures weekly at my parents' dinners and lunches, and whose ancestry spans a large geographical arc, I feel we must nourish ourselves as networked people of this planet.

I still believe that remaking our society in so-called Australia to centre on Indigenous peoples, lifeways, and relations is possible and vital to planetary survival. The Great Ocean remains one of the most connected regions, crisscrossed with high flows of people and ideas, despite a few hundred years of border-mongering decided in Berlin, London, Paris, Washington, Tokyo, and Beijing.

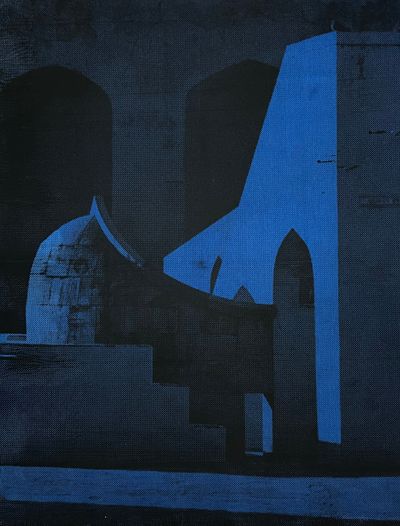

I recently learnt that not only was my Sāmoan/Cantonese/European grandmother an artist, but my Persian grandmother, whom I never knew, as well. They innovated in customary art forms within vastly different contexts, but ones in which women had more and more agency in the 1970s into the 80s.

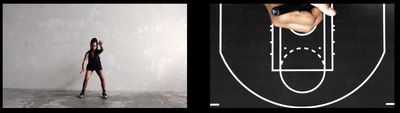

RCYour own art practice references your Sāmoan, Persian, and Cantonese heritage and involves performance, moving image, writing, and installation. You have described yourself as interested in engaging with Indigenous futures as haunted by ongoing violence that once erased fa'afafine and faʻatama people from kinship and knowledge structures.

Can you talk a little about these kinship and knowledge structures?

LEBy kinship and knowledge structures, I mean the sociopolitical organisation of village-based polities in the pre-colonial Sāmoan archipelago, where we had eight chiefdoms that were played against each other by the colonising Germans and Americans, who swooped in with a bifurcation treaty in 1899.

Faʻafafine and faʻatama (sometimes termed faʻatane) have always held a central role in the expression of the arts and sciences in Sāmoan culture, but this centrality was perceived as a threat and severely eroded by the rabid missionaries who followed the first John Williams in 1830.

I reject their imposition of Gregorian shame-time as well as their wholesale reorganisation of society to the exclusion of non-monogamous, non-heteronormative ways of knowing, being, and relating with more-than-human, human kin, and places.

RCYou have said that your practice is anchored in considering Indigenous ways of being, organising, loving, world-making, and caring that pre-date and will post-date Euro-American norms and knowledge. How do you explore this in your performances and curatorial projects?

LEI seek to place the works I create with my body—especially my hands and voice—as much as with the display territories I organise as a curator, in continuing hxstories. The artists or knowledge traditions I work with are not new, except to interculturally illiterate or perhaps uncurious audiences.

Curatorial practice mostly allows you to serve others, organise space, and honour hxstories that require recognition.

I am invested in living and realising relational time-space with kin and colleagues alike and seeing how these connections can be made evident in registers of speech and text, the translation or not of motif repertoires, and the choice of customary colour palette or hues more associated with futurisms.

I think questioning the inherent referentiality of Greenwich standard time, the International Date Line that dissects my homeland archipelago, and especially the Christian calendar are ways to demonstrate that humility to local traditions is nigh.

RCThere have long been calls for artists to curate the next biennial. Most recently, the Indonesian artist collective ruangrupa curated documenta fifteen (2022), while Wiradjuri and Celtic artist Brook Andrew directed the 22nd Biennale of Sydney (2020), the first time an Indigenous Australian led the Biennale in its 47-year history.

Do you see yourself as an artist who curates, or a curator? How does your work as an artist inform your curatorial work?

LEInterestingly, I don't identify as an artist who curates, but more as a curator who makes art a few times a year, when the right project manifests. I enjoy switching roles throughout the week or month writing about artists and artworks, curating meeting spaces with them, and that emphasis on relationships and growing ideas.

In terms of research-creation, I do see a clear through-line between what and how I make as an artist and as a curator. They are two sides of the same cultural imperative.

Curatorial practice mostly allows you to serve others, organise space, and honour hxstories that require recognition. Though I think I have a special respect for creativity as a curator who is also a practising artist.

Brook Andrew's 22nd Biennale of Sydney was a good example of what Lana Lopesi terms a Moana cosmopolitan imaginary, based in part on remixing various influences, and in part on asserting Indigenous knowledge and trajectories.

RCYour forthcoming curatorial project, the 8th TarraWarra Biennial, is titled ua usiusi faʻavaʻasavili, a Sāmoan proverb meaning 'the canoe obeys the wind'. What does this proverb mean for you, and why did you choose this title for the Biennial?

LEI don't often get to speak my mother tongue, Gagana Sāmoa, so I carve out a space of intercultural understanding when I title artworks or exhibitions in my language. For the title, I was thinking through the many deities we have in the Sāmoan archipelago, as well as the many expressions in Gagana faʻalāuga (ceremonial orature) that relate to endangered or extinct animal species.

These expressions are rarely used today with the expatriation of the majority of Sāmoans to other Indigenous territories in Aotearoa [New Zealand], Australia, Hawaii, the United States, the United Kingdom, France, and Germany. By speaking this proverb, we can bring back some of its original purpose and strength, by centring the planet above ourselves as human beings.

RCWhy is this subject so apposite now, and what are some themes and ideas you hope to explore through your selection of artists and artist groups?

LEAt this point, I do think that the most transformative action is to commit to becoming good neighbours, stronger in the diversity of our differences and in full exercise of a cosmopolitan worldview and practice.

The incredible artists in TarraWarra Biennial 2023 delve into climate grief, cultural memory, animal-human relations, gender euphoria, transnational learning, innovation in customary art forms, ancestral spectrality, queer representativity, respect for elemental spirits, and object translation of Indigenous languages.

Other themes they contend with include deity presencing in new contexts, racial hierarchy, residues of plantation oppression, making with intertidal habitats, the intersectional experience of athleticism, and the honouring of kin plants and waters. I am so honoured and grateful to all these artists.

RCFifteen artists and artist groups feature in the Biennial. Can you talk about some of the works that you have selected for this exhibition?

LEHaving worked with kalikina (bull kelp) over many years, including making rikawa (water carriers), Trawlwoolway artist and educator Vicki West's offering kalikina brayly (2023) is an immersive invitation that carries 'concerns for country/sea' while celebrating survival and cultural continuity. The aerial perspective honours the continuing importance of creating carefully and relationally with kalikina, which has been weakened and threatened by warming currents in recent years.

Many of the artists are bringing a longer temporal angle to understanding humanity's remaining agency in the aftermath of such colossal storms.

In PERMEATE | mapping skin and tides of saturated resistance (2023), The Unbound Collective—a long-standing collaboration of legendary First Nations artists and scholars Ali Gumillya Baker (Mirning), Faye Rosas Blanch (Mbaram, Yidindji), Natalie Harkin (Narungga), and Simone Ulalka Tur (Yankunytjatjara)—focuses on the spiritual and cultural flows impeded by increasing and irreversible salination of the few mangroves remaining in Kaurna Country [Adelaide].

This is a lament carried through breath and its absence: it's not as widely known that mangrove forests and seagrass meadows hold more carbon than forests and plains.

Ngugi Quandamooka mother-daughter duo Sonja Carmichael and Elisa Jane Carmichael crafted Ngumpi (Home) (2022–2023), a sublime installation that affirms and strengthens their spiritual connections to ancestors, sea, and land.

The installation champions the sovereign balance of relationships between humans, more-than-human kin, and their archipelagic homelands, especially the larger Minjerribah and Mulgumpin islands [Stradbroke and Moreton Islands, near Brisbane and Queensland].

Gulumerridjin (Larrakia), Wardaman, KarraJarri, Japanese, Chinese, Filipino, and English artist and designer Jenna Lee's large installation to gather, to nourish, to sustain (2022–2023) is the culmination of years of research-creation into objects that embody the Gulumerridjin language from its absence and presence in colonial archives.

For the Biennial, Jenna crafted three dilly bags from pages of Gulumerridjin language dictionaries compiled by colonisers and more than 45 diamonds bearing verbs as images.

Sancintya Mohini Simpson, whose ancestors were taken from Chennai, India, and made indentured labourers on sugarcane plantations in Natal Colony (now KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa), focuses on rendering intergenerational accounts through works that redress archival absence, as well as racial, gendered, and caste asymmetries.

Migration, memory, trauma, silence, and hauntings within a matrilineal prism find form in An ocean (2023), an assembly of black clay lotas fired in sugarcane and sawdust, with a sound composition by sibling artist Isha Ram Das.

RCMany of the artists you have selected for previous projects identify as Indigenous or LGBTQ+, and their diverse cultural and activist practices offer alternative narratives to the racist and gender stereotyping that you note has often been a feature of many cultures and past exhibitions.

Does this need to be a shared conversation when you want to reflect the times in which we are living?

LEI would affirm that the experiences and aspirations of the majority world deserve ample airspace and rigorous embrace. The more voices and more informed the conversations, the better a society we will be.

RCIn recent years, parts of Australia suffered devastating environmental crises—floods, fire, rising sea temperatures, and mass bleaching on the Great Barrier Reef. Is there an urgency that you have seen artists responding to, and how has it affected your thinking about the biennial as a platform?

LEMost definitely the recurring and intersecting climate crises of recent years and months across Australia and neighbouring archipelagos have been high on all our minds and concerns.

This is not a climate change exhibition, however. I think many of the artists are bringing a longer temporal angle to understanding humanity's remaining agency in the aftermath of such colossal storms. I wholeheartedly reject the biases of the Anthropocene and other Eurocentric categorisations of this era in the same breath; colonising current and future eras is not the way forward.

I have been thinking deeply about the ecological and emotional sustainability of exhibition series such as the multiple biennials and triennials in every OECD country [Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development]. I think this platform brings specific responsibilities to the communities I have been mentored and nourished within, across and beyond Australia's shores.

RCYou've talked about presenting hidden exhibition histories through your art and curatorial projects, rather than reinforcing historically dominant perspectives and views. How does your work achieve this, and why does it matter?

LEToday, I prefer talking about literacy and illiteracy in hxstories, rather than unknown/known or hidden/discovered traditions. Inhabiting this queer non-binary faʻafafine brown body, I cannot be a conventional Eurocentric cis-heteronormative body. I have to champion a panoply of hxstories and perspectives and do my best to read beyond Europe and cite beyond English.

Every language offers its worldview. I speak Sāmoan, Bislama, Tok Pisin, French, English, and Spanish, and am learning Hawaiian, Dari Persian, and Anishinaabemowin. I want to learn from within and become a better neighbour.

RCLastly, your installation AOAULI (VILIATA) (2020–2022) was presented recently in A Clearing in the Forest: Enmeshed at Tate Modern, London.

What are some differences between working with an institution as an artist rather than a curator? Are there things that art allows for, but not curation?

LEThere are topics that I can only express through artwork. Particularly when working closely with my sibling, the artist, designer, and DJ, Nadeem Tiafau Eshraghi, such as the digital prints on silk we made that were shown at Tate Modern and QAGOMA, or art projects made with other close friends and family.

When working as an artist, I often see the limits of the institution and the opportunities for intervention and reaching audiences. Whereas with my curator hat, I have a fuller understanding of the structural limitations that are often beyond a curator's capacity to shift. A good dose of moderation to both perspectives. —[O]