Decentring Art and Craft: The Manchaha Project at Nature Morte

In Partnership with Nature Morte

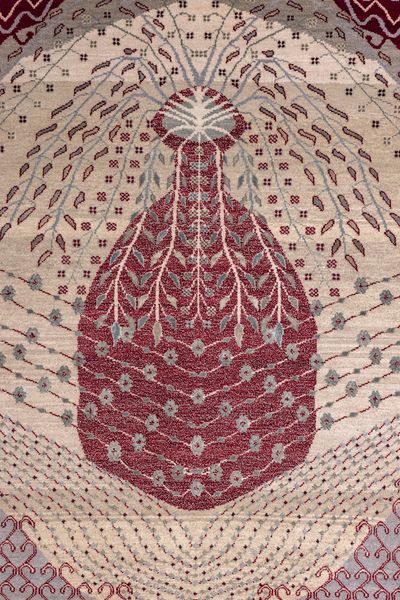

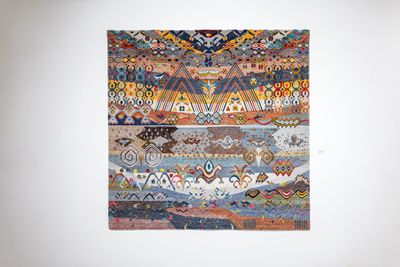

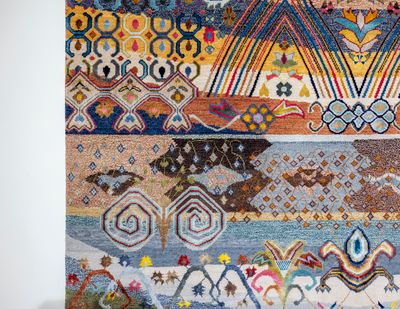

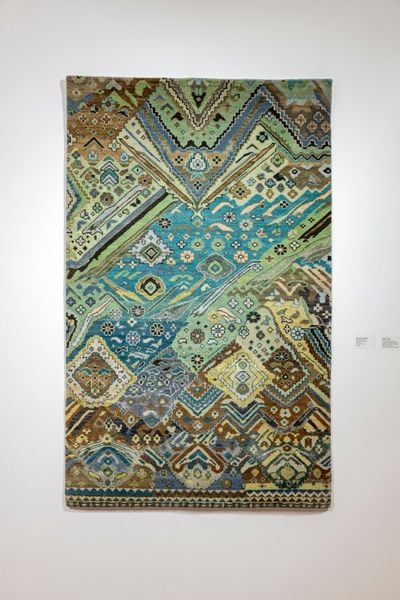

Vahid Khan, Dhaari-Dhaari (2021) (detail). 182.88 x 182.88 cm. Wool and bamboo silk. Exhibition view: Hanging Gardens, Nature Morte, Delhi (29 July–28 August 2021). Courtesy Nature Morte.

Vahid Khan, Dhaari-Dhaari (2021) (detail). 182.88 x 182.88 cm. Wool and bamboo silk. Exhibition view: Hanging Gardens, Nature Morte, Delhi (29 July–28 August 2021). Courtesy Nature Morte.

At Nature Morte in Delhi, the exhibition Hanging Gardens (29 July–28 August 2021) marked a departure from the gallery programme's fine art focus to encompass craft and design.

Developed by designer Kavita Chaudhary, the Manchaha project is one arm of her company Jaipur Rugs—a family business that works with rural communities across Gujarat, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and Jharkhand to provide opportunities to artisans, building upon the 2,500-year-old history of rug-weaving.

The project, which Nature Morte founder Peter Nagy first encountered at the Serendipity Festival for multidisciplinary arts in Goa in December 2017, works with local artisans in villages in India, as well as inmates of prisons, to produce unique rugs. With no formal training in design, most of the weavers have inherited their skills from parents and grandparents, and produce rugs upon manufacturer's design briefs.

Manchaha does away with such briefs, allowing weavers to use the medium as a means of self-expression for the very first time.

Embedding looms in prisons as well as the homes of weavers, this format of decentralised rug manufacturing invites the transformation of dynamics within families and homes, with designs becoming a 'source of empowerment for local women and a means to reconcile their status in social and familial settings,' explains Chaudhary. In the case of prison inmates, the engagement with rugs allows weavers to sift through unresolved feelings as they work.

The rugs have been met with zeal from design enthusiasts, and with the art world's growing interest in craft—the reflection of a desire to engage with more physical art forms, Nagy speculates, as a reaction against technology—Manchaha is attracting broader audiences.

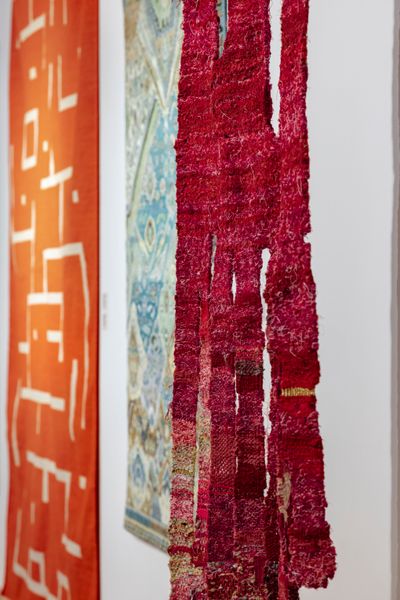

Hanging Gardens included six tapestries by weavers engaged in the Manchaha project (Vahid Khan, Mahaveer, Koshalya Samrthpura, Meena Dhanota, and Savitri Samod), with smaller designs opted to approximate the works to paintings. Also on view were experimental textile works by Sayan Chanda and Sagarika Sundaram, both artists and weavers, further blurring the line between art and craft.

On 16 August, Kavita Chaudhary and Peter Nagy met online to discuss the project. Below is a modified version of the exchange.

PNKavita, could you explain to us what Manchaha is?

KCManchaha is a project where we take weavers from the commercial carpet industry and transform them into artists, in a sense. The loom becomes their canvas, and they are free to create like artists.

The project gives them the opportunity to make rugs with whatever inspiration comes to their hearts and minds. Normally, in commercial handmade carpet production, you always have a predefined drawing, and through the drawing, you're always copying motifs and colours.

Those are the standard steps for creating a handmade carpet. But for the Manchaha rug, there is no predefined drawing or colour schemes at all. The weavers define and choose their own way in which they want to progress.

The beauty of a Manchaha rug is that sometimes multiple artists sit on the same loom, working together for two to three months or more. As they start weaving, they are often unsure and afraid of what they want to make, because they haven't done this before.

They start by testing patterns on little areas, and then as they gain confidence after a few inches of weaving, they start exploring their own identity and their personalities come into play.

As the carpet takes a long time to make, the initial idea or theme evolves and transforms into an original piece of art along the way. This is the extraordinary beauty of the weaving process. The slowness of it enables the artists to build upon their ideas.

Manchaha is a project where we take weavers from the commercial carpet industry and transform them into artists, in a sense.

Most of the artists are from rural India, who have no background in design and haven't actually gone out of their towns, cities, and villages much. They don't have exposure to design like most of us here.

What they create is actually very spontaneous. They choose their own colour palettes based on what is available to them and what is sent by the organisation, and start creating these patterns. That in a nutshell is Manchaha for you.

PNWhen did you start, and what inspired you to do this? It's quite a radical gesture on the part of a big commercial rug manufacturer.

What we can assume is that many of these weavers probably have parents who were weavers too. So it's a vocation and the technique has been inherited. Is that correct?

KCThe idea was born from the need for a new design-thinking that pushed the envelope. It started with the very first Manchaha rug design, called Anthar.

Unlike most designs born in the design studio, the Anthar rug was born directly on the loom, and it was influenced by the misalignment and alignment between its weavers. That set the stage for Manchaha, which has demonstrated numerous complex human relations on the loom. It gives us original art directly from the most repressed communities of rural India.

The weavers making these rugs are both first and second-generation weavers. The dying art of hand-knotting has been nurtured through passion and sustainable development, all woven together into one-of-a-kind rug designs that can connect hearts world over.

Jaipur Rugs doesn't have a factory-based model. The looms are set up in the weavers' own homes, creating mini production units. With this, the weavers can create handmade pieces of art out of the comfort of their homes.

The beauty of a Manchaha rug is that sometimes multiple artists sit on the same loom, working together for two to three months or more.

PNAre there weavers who are more adept at using silk or more traditional designs than contemporary geometric designs?

KCThere are very few weavers that limit themselves to traditional designs, out of preference. The majority of them are pretty open to weaving all kinds of patterns and working with all types of yarn. The types of orders in production also depend a lot on client orders. So they're quite flexible in terms of what they do.

PNAnd then they are trained following a pattern. Is that right?

KCYes, that's what they do and that's what they've done for a long time. When we launched the project, and we invited them to make their own carpets, I think most of them were a little surprised. They were like, this is not possible!

PNIt's a gift of freedom, but it is also a lot of responsibility. I mean, this is their livelihood and the way they support their families, so there must have been fear or anxiety on the part of the weavers?

KCI would say that for 60 to 70 percent of the weavers, there was a lot of fear. I remember the reaction of the whole village where we sent some bags. We were like, 'Just play around, don't worry!' One of things we always told them was to connect with their hearts.

They already make so much in their village with their hands, like quilts and clothing for their children, so we were like, 'You just begin how you would begin another piece of art in your home. Just begin the way you want.'

PNI am just wondering about the financial arrangement. If they are continuing to make patterned carpets, do they have to create these new designs during their off time? Or are you paying them to make these?

KCThe loom can only house one rug at a time, so if the weaver is making a Manchaha, she can only do that until she finishes the carpet, which may take a few months.

Once she is done with the Manchaha, she might continue with another Manchaha or she might get commercial production. The payment is regular regardless of the type of carpet being woven.

PNThat's up to the weaver at that point?

KCNot entirely up to the weaver, I would say. Some part of it depends upon system requirements as well. It depends upon the client orders we have also. The team will always try and adjust things. There are some weavers who are really passionate for Manchaha, so as long as the system is stable, we let them continue doing that.

PNWhen I was looking through your inventory of things to choose for the show, I noticed that most of the rugs are large, because of course people generally want large rugs that fill their rooms. But because I was choosing things to hang on the walls of an art gallery, I was going towards smaller pieces, so they wouldn't overwhelm the other pieces in the show and they would appear more like paintings.

There was a lot to choose from, and I really just went by my eye. I wanted to have a diversity, to show the range of what's possible at Manchaha. But really, as is always the case with curating a show or looking at things, you're just looking for things that you like and that hopefully please your audience as well.

Do you have certain weavers that are stars of Manchaha, who are not going back to the pre-programmed mode of production?

KCDefinitely, there are quite a few weavers who are the stars of Manchaha. And it is fair to say that they make more Manchahas than production carpets.

PNWhen you started this, you said you really didn't know where it would lead you in terms of how you would market these things or where they would fit within your much larger carpet business. You have a corporate headquarters in Atlanta to handle American distribution, so you work with a lot of designers there. But you said these Manchaha pieces didn't fit into your marketing set-up very easily?

KCYes, that was in 2011. When the project first started it was just rounds of experiments. Back then, like you said, we were used to larger sizes, so I chose eight-by-ten-foot carpets. I made 100 of them at that time just to experiment.

It turned out to be a mistake, because I realised that the dimensions were too large for very unique pieces. And, of course, the customer base we had at that time was extremely traditional. They were only shopping for traditional carpets.

PNIn the sense that you weren't happy with the results, or that you weren't able to sell these things?

KCWe didn't have a good response in the marketplace at that time.

PNBut for yourself and the weavers, you were happy and excited about what had been created, right at the beginning?

KCYes, a lot of the weavers were very excited. For some of them, it was the first time, and the design language that was emerging was incredible. We were even sort of embarrassed by some. This one carpet had a large lotus, a little tree, and a monkey sitting on the tree holding a gun shooting a rabbit. And I was like, 'Oh my God, what are these demons? What are they making?' It was a cultural surprise for me as well at that time.

But later, as more customers saw it, and as the story went around, everybody was asking for the 'monkey with a gun' rug. Very early on, a lot of new imagery that we hadn't seen in carpets before started emerging. It was surprising in some ways, and really exciting.

PNYou must see certain weavers break out of the box. I mean, surely they are very hesitant on their first one, and then slowly they get crazier?

KCSome weavers start out really bold. I've seen male weavers and weaver couples have no fear holding themselves back—they just put in whatever they want.

And then there are those that start in a very timid way. They're not sure and they want to build on a very tight and intricate pattern. So, I think it happens both ways. Some build up their strength after a few Manchahas and some explore it in the first one.

PNLooking through your inventory, it was quite amazing to see the range of different things going on. And I tried, as much as I could with just six pieces, to represent that in the show. Of course, there are rugs that lean on more traditional carpet motifs that are inherited from the more traditional production, and then they tweak that, and others don't seem to pay any attention to that at all.

You can sort of see seasonal changes in the carpet quality itself, or even psychological changes. When I was in Jaipur at your place, you showed me one that a husband and wife had started together and there was a story about how that changed over time. What was that story?

KCThe rug is named Savan ka Laheriya and it is made by a young weaver couple with a child. The wife spends most of her time with the child and only a couple of hours on the loom each day, and the husband does the main weaving. It's a large eight-by-ten-foot rug.

The husband was weaving six feet, and then the wife was weaving the neighbouring two feet of the carpet. The husband started out with a rhombus pattern, very organised and very clean. And the wife started out with laheriya or zigzag patterns—very abstract lines, which she represents as a laheriya. As the rug progressed, the husband insisted that she follow his pattern.

Very early on, a lot of new imagery that we hadn't seen in carpets before started emerging. It was surprising in some ways, and really exciting.

So the wife goes, 'Well no, we were told to do whatever we want and I like this better. I like my laheriya better.' So the husband is very insistent and tries to convince her because he's so sure that what he has made is more beautiful than her side of the rug.

So he actually went to the neighbours, and asks a few of them, 'Why don't you come to the loom and help us resolve this? What do you guys like? Do you guys like this side or that side?' And everybody immediately preferred the wife's side. He concedes and they end up making the wife's design all over the rug. The rug won several international design awards eventually.

PNAnd it was only one third, compared to the two thirds that he had?

KCYes, only a small portion. And they all said that it was more original. And the husband's ego just melted right away. He was like, 'My gosh, I had no idea she was the artist in the family—I always thought I was the artist in the family, and now I dedicate this carpet to my wife, and I'm going to follow her pattern.'

PNManchaha is smashing the patriarchy!

KCThere are so many examples of real changes in the families where women were once overpowered, and the relationship completely transforms.

As a result, the wives bring dignity into the house—she brings in the money and recognition. So much so that the husband will sometimes cook for the guests, and allow the wife to talk to guests.

There is this beautiful story of a woman weaver who won this international award. After winning the award, she went for an interview at one of the newspapers in Jaipur, where her son had come along.

When he saw his mother on the stage talking confidently about her work, he realised he had mostly taken her for granted and he had never respected her so much. Suddenly, his whole impression changed.

There are very few weavers that limit themselves to traditional designs, out of preference.

She never quite had the freedom to choose. It was surprising to hear that all her jewellery was bought by her husband. She had no decision-making power to even choose her jewellery.

After making a Manchaha, she went to the market and chose her own pair of earrings. Her husband sort of shouted at her. But over the years as her Manchaha rugs brought her fame and recognition, their relationship transformed.

He no longer controls her and totally accepts her as her own independent creator. So many stories like these have happened, where relationships are completely changed within families.

PNIt's easy to extrapolate just because of the nature of weaving on the loom. The carpets can be read as psychological charts or diagrams of relationships, of communities, and how things evolve.

After you told me that story, I started looking at them differently and read into the choices of colours and motifs. It's interesting when the carpets almost become sociological evidence of relationship dynamics, for example, which does overlap with how Western artists are thinking about using textiles.

Storytelling is also a big thing. I'm looking at different forms with more traditional routes to negotiate ideas of hybridity and to describe how tradition moves on, and to consider gender-based practices, as well as how objects like this move into markets in new ways.

Over the last few years, Aparajita Jain, my partner in the gallery, and I had been thinking about whether we wanted to move the gallery into a design space. About four years ago, we decided not to, because we had enough on our plate and felt we wanted to keep Nature Morte to a more defined fine art practice.

But with the move that we made last year, we now have more space, so there can be more flexibility in our exhibitions. And we both love design. There are a lot of interesting things going on with design in India.

It's taken four years since discovering Manchaha to bring it into an exhibition. Is this the first time the works are being shown in a fine art gallery context?

KCYes, we have not shown them very much.

PNThere is a big movement in the art world in the West called Outsider Art, which is an umbrella term for people who are untrained in the fine arts. And they were not really part of the larger art world, yet they sometimes made very large bodies of work, which often don't get seen until very late in their lives or even until after death.

But now it is a very popular category and there are art fairs dedicated to Outsider Art, and many mainstream galleries and museums are bringing this type of material into their exhibition programmes. A couple of years ago, the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. had a very large exhibition called Outliers and American Vanguard Art (28 January–13 May 2018).

That's another way of looking at these Manchaha pieces. These people are outsiders to the traditional fine art world, and they're being given the license and the facility to create things from their own reality.

But what's interesting is they're still coming from a tradition and a technique that they've mastered, in many ways. I think that's the quality of what I'm seeing in the Manchaha project, I think it has a lot to do with the fact that these people are often second or third generation trained weavers who are very familiar and comfortable with the process, right?

KCThat is not exactly true. This may apply to some of the weavers who've been making carpets over time. But, for example, we launched the project in prisons in Rajasthan and most of the inmates did not know anything about carpet weaving.

So, when we launched the project, we began by training them in Manchaha. When they learned to weave, they wove the Manchahas. Of course, the first few carpets had a certain unique quality. As more carpets got woven in the jails, they were just exploding with joy and all the emotions.

It can be difficult for the men to let out emotions. And we realised that the rugs became psychological maps and the inmates where expressing the emotions of what had happened in the past.

PNWow, were they able to articulate that through the imagery? Or it was done in a very abstract way?

KCA lot of it is abstract. But there are some motifs and symbols that you can recognise. The inmates don't usually make them too large, but if you pay attention to the details around the rug, you can find the motifs at times.

PNIn India, weaving is predominantly seen as a male vocation. So you wouldn't get pushback from inviting men to create carpets, per se, but you might if you were asking them to create embroidery, or some other techniques more associated with women.

So how much of Manchaha production is made by people in prison? And people doing it from their homes? What's the proportion?

KCThat's a great question. I think the prison workshops are running really well. In terms of distribution, 40 percent might be created in prisons and 60 percent in villages. In the prisons, they make larger carpets, and more people sit on the loom.

There are so many examples of real changes in the families where women were once overpowered, and the relationship completely transforms.

All the looms are set up in one place and it's more like a production unit as compared to the villages. They have eight to ten looms operating at a given time and more people work together, which is why they will always build up more speed.

Through the Manchaha rugs, the inmates start building a community of people who come together together and have conversations. Invariably, the speed is much faster in prisons than the speed you would have in a house with people operating individually.

PNThe names of the weavers are kept with the pieces, which are also given titles. So we're handling these carpets the same way as we would handle a painting in our systems at the gallery, and now we are promoting them in the same ways.

But can you see this becoming problematic when there's more than one person making a single piece? I mean, you can see a husband and wife doing it together easily but four guys in jail? No big disasters there?

KCI think that makes the process more interesting, from what I understand. A lot depends on the personalities of the people who are working. Sometimes there are dominant players, sometimes the people are very clear about what they want, and they inspire the rest of the team. And sometimes they don't really align together, and they'll start creating their own sections on the rug. In the end, you always find that in some way, they start interacting through the Manchaha.

PNWell, I would imagine the guys who are teaming up in jail to make something are probably already buddies or something. I mean, you're letting these teams come together organically, right?

I suppose that the people in the jails are chosen to do this. I mean, it's just offered as a possibility, and they're being paid for it as well. Is there some difference between what you pay the prisoners in jail and the people at home?

KCThe work in the prisons depends entirely on the will of the inmates. No one is forced or supposed to work. The jail pays a little bit higher because 25 percent of it goes to the prison department for different programmes.

PNDid you bring the looms into the prisons?

KCYes, and we had a training team that stayed with them for a long time, to get them to improve their quality.

PNHow many prisons are engaged now?

KCAt the moment, it's three prisons. And just yesterday, we reached out to a new prison where they were really excited about the work from other prisons. The in-charge asked to get it started right away, because she saw a lot of joy and transformation in people though this work.

PNWhen I was in Jaipur at your place last month, we looked at piles and piles of pieces. The home productions and prison productions were all mixed together, right?

KCYes, at the moment we are showcasing them together because we have limited space. So, a four-by-six-foot Manchaha from the village is showcased along with the one from the prison.

PNI couldn't see any radical difference in the designs or anything. I had no sense that there were rugs made by incarcerated people and others by people in their homes. That didn't seem to come through in any way, shape, or form. Even with the prison ones, you're still putting the names of the individuals on there.

I think we have about two more weeks for the show in Delhi and then you are going to bring a couple of the weavers to see the show.

KCYes, I think four of them should be able to make it soon. They're really excited to visit.

PNTo see their works hanging on the wall with other things! It will be interesting if they change anything after seeing their works in the gallery.

We've gotten fantastic responses on social media by posting images of the works. A lot of people in the art world are always looking for new forms, new techniques, new materials of expression, and the Manchaha project is plugging into that desire.

You can see trends in the art world where people gravitate to a certain kind of art. And then I think that the eyes and mind get used to that and then they want to go to another extreme.

Throughout the 20th century, the pendulum swung back and forth between abstraction and figuration. I think a lot of the interest in textiles and ceramics in the fine art world is simply a reaction against technology, because so much of our lives is on smart phones and laptops, so people crave art forms that are more physical.

I think in the art world, we've seen a big drop off in interest in photography, where 20 years ago photography was something new and exciting in the art space, specifically in India. We showed a lot of it and we got a lot of attention for it. And now I don't feel that there's much interest in photography, simply because we're all basically inside the photograph all day long.

When looking for aesthetic experiences, people want them to be more tactile. They want things that are coming more from the realm of crafts, because they feel more satisfying in many ways.

KCI completely agree. In fact, a lot of the interior designers who were earlier buying the Manchahas for their projects or for their clients, are now beginning to collect them.

They keep checking out the range and some of them have bought like 20–30 pieces because in about 10–20 years they'll be in demand due to their uniqueness. The Manchaha rugs have such a definitive design language.

It's the simple idea of a one-of-a-kind, hand-woven carpet made by an individual's free spirit. It's a very radical idea. We have thousands of years of carpets out there, but this is a pretty new development, actually.

It's great that as a large carpet company, you have the financial facility to allow this to happen, to democratise the space and empower people, in a situation where other people simply couldn't afford it. You guys took a big risk producing 100 eight-by-ten carpets from the get go.

KCYes, I think it was a big risk. But when creating something unique in the rug studio, it's always a risk. You never know how things will go. But I think we all love the project very much and this is such a transformation.

We are seeing so much excitement from the clients, so we know that it's going in the right direction. The risk is totally worth it for everybody. It's really transformational.