Yee I-Lann on Relearning Differently in Borneo

Yee I-Lann. Courtesy Silverlens.

Yee I-Lann. Courtesy Silverlens.

Yee I-Lann is an artist whose unique exploration of geopolitical histories in Southeast Asia is embedded in locality and personal experience, which has been tracked in major institutional exhibitions including the Ayala Museum in the Philippines (30 August–4 October 2016), and her upcoming solo exhibition at CHAT (Centre for Heritage, Arts & Textile) in Hong Kong (1 September–7 November 2021).

In the artist's single-channel video PANGKIS (2021), a septuplet of male dancers carries a canopy of woven tubular cords, which are interconnected and sprawl out from individual hats. Bodies interlock while emitting guttural calls as feet tap the floor: a visual symphony of sound and movement that affixes the 7-Headed Lalandau Hat (2020) in a support-searching choreography. The image animated the ecologies thriving in the artist's recent exhibition Borneo Heart at Sabah International Convention Centre (1–31 May 2021).

Openness cuts the distance between the head and the heart. For PANGKIS, which documents the contemporary performance of Tagaps Dance Theatre, I-Lann collaborated with local weavers to transform the traditional headdress used by Murut warriors. She turned these open protrusions in the hats, which used to be filled with argus bird feathers, into arteries that would pulsate through individual, living bodies.

In a similar vein, I-Lann centralises orality in connecting head and heart when she transposed the popular lyrics of Sabah's folk songs onto a large-scale bamboo mat titled Dusun Karaoke Mat: Ahaid zou nohdoiti ('I've been here a long time'). The familiarity of the text on a hanging object instantly switches the position of exhibition viewers, especially local Sabahan visitors, from readers to singers.

The conversion of agency in I-Lann's exhibition installs the public's presence into a shared soundtrack composed by the burst of songs from her community. For the artist, these iconic melodies resist the homogenising cultural import of peninsular Malaysia to the eastern region of the country. Reproducing speech, voice, and memory in front of a social artifact recently translated to an artwork charges daily materials found in the social sphere to be an artistic compass shared with her constituents. Such improvisation in form and style unbinds rationality and emotionality in practice.

After decades of exhibition itineraries outside her hometown, I-Lann loops back her artistic thread firmly onto the knots and patterns of creative transmission in Kota Kinabalu's vast vicinities. While the artist has consistently referenced local sociopolitical histories in her works, Borneo Heart presents the further removal of blockages and remnants that impede the flow of relationships across psychic and geopolitical borders.

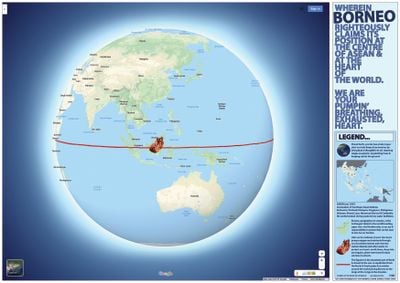

The ancestry she finds in weaving and co-making with her fellow Sabahan artists is a rhizomatic lineage that recruits other circulation, respiration, and exhaustion. She offers this new inheritance, as if it was a task for the next generation of artists, when she declares that Borneo is at the heart of the world.

I-Lann's collaboration with weavers from Keningau in the Borneo interior and Pulau Omadal, Semporna, in the Sulu-Celebes Seas, began in 2018, as highlighted in her exhibition of mats at Silverlens in Manila (ZIGAZIG ah!, 7 December 2019–11 January 2020). For I-Lann and the weavers, the mat is the surface and volume of life lived in every stitch and shape with minimal cushion.

In this conversation, I-Lann discusses the production of Borneo Heart, which happened in a more personal context, and follows the development of ideas and communities on the mat. The artist pulls these stories closer to tanah (soil), tanahair (homeland), where the mat is rolled out or unfolded, sharing them without self-elevating the contribution of a singular artist in a collective cultural enterprise.

RLThe commitment to becoming less solitary as an artist based in Kota Kinabalu and whose new works are sited in the day-to-day ecologies of the city might be a tender entry point to our conversation.

There is materiality in loneliness, and I wonder how it is enfolding your artistic subjectivity. The environment where you exhibited in Sabah goes beyond the standard of exhibition-making we are used to. In this context, collaboration and conviviality seem to reorder the priorities of exhibition-making, in which technical precision is approximated and recalibrated all the time.

The image of the mat invoked a sociality embedded in productive constraints: the mat welcomes and determines the number of people who can fit on it. Whoever comes needs to adjust their body to the bodies that will receive them. Such a nourishing analogy is presented here in the way we are working today in unfamiliar contexts with limited conditions, and how we can work from places dear to our hearts, say our hometown. How do you present art in places like these?

YII had become used to working in expected art spaces and am not usually this involved in the actual staging of an exhibition. Making this show made me judgemental about what I have been doing in the past somehow.

Borneo Heart had a limited physical audience because of Covid-19 restrictions, but the quality of engagement felt different. My investment in the exhibition felt urgent and personal. For example, the Artist-Tour conversations, which happened three times a week, would expand down diverse tributaries depending on who was present, in ways I hadn't quite experienced before.

I just want the museum to be more like a market, and more like a mat, in that true sense of an exchange of objects, knowledge, balance, and value systems: systems that are circular, restorative, and regenerative. I know it's there in museum studies, but I kind of lost touch with it.

How do you present art in a place that is close to the heart? I loved drawing from the familiar in local thinking and knowledge—like the tamu—as guiding inspiration, and presenting this back to my hometown, a bit like a love letter, as if to say, 'Look how beautiful you are.' I am still feeding off the energy of letting go, trusting, sharing, and crowding the tikar with fellow creatives.

In Borneo Heart at Sabah International Convention Centre, I have been learning how to put up an exhibition. I had mounted dozens of exhibitions previously, but I am relearning so many things now. I'm relearning them differently. It's exciting!

I'm excited about our process. Normally, exhibitions are the be-all and end-all of an artist's production. With Borneo Heart, it is the whole process. It is not just about the exhibition.

We have a limited history in Sabah in terms of 'formal' exhibitions. Working in Sabah with the Kuala Lumpur-based curatorial and project management team Beverly Yong and Rachel Ng of RogueArt invited a rethink of basic structural questions about how to make an exhibition, put together a public programme, find spaces, who to collaborate with, and so on.

It's scary exhibiting in front of my parents, aunts, uncles, cousins. They haven't been to many, or any, of my exhibitions. My mom is a teacher and my dad a retired civil servant, so we know a lot of people. It's a small city. That adds to the scariness, but overall it has been a deeply educational and enjoyable experience.

RLThese anxieties in your journey almost constitute the practice of reintroduction and reimmersion into a new place, where you become a guest. It is also about revisiting what art is and what art can be.

This composes a fundamental question and reality where art can emerge after or during its relocation in parallel systems of the artistic realm, outside the usual power corridors of presentation. The primal experience of exhibition-making is resituated.

Your characterisation of these curatorial ventures is a form of artistic reorientation I suppose. The artist is being exhibited and being seen by different relationships. There is kinship in exhibition-making, which sometimes I feel has atrophied in the standardisation of art practices or aggressive professionalisation of the art world.

Joy is the language that I can attach to this exhibition, but I wonder what kind of joy can we actually promote within exhibition spaces?

YII love that you used the word 'joy'. 'Joy' and 'play' are two words that I use all the time. They have overriding sentiments. I really think that play is the most important four-letter English word. The other four-letter English words—'love', 'fuck', or 'work', for example—seem lifeless to me without their relationship to 'play'. The act of play isn't flippant; in fact, it's the opposite—during these pandemic times, joy and play feel like a kind of methodology to fight against oppressive feelings.

While a lot of play invites joy, it's also unsettling. The other scary thing is you can't fake it. A lot of my previous artwork has been about Sabah but usually exhibited elsewhere, there is a certain anonymity about it.

Over this difficult past year, I think the vitality of the local has been stressed. There are many locals present within this exhibition and also viewing it. I am questioned about the people I am collaborating with and why. We talk politics. The interaction through the artwork manifests in very diverse and direct conversations and hopefully sparks something in thinking about ourselves and art.

That's another aspect of production and conception that I have learned in working here: how you interact, listen, and understand something initiates the artist's or the exhibition's framework. Talking to people who know what you are discussing registers things, concerns, and ideas differently as compared to theorising them to people who may not understand what I am referring to.

RLThe semantic closeness of 'extreme' and 'extremities' is confrontational. I sense that there is a threshold here that is successfully crossed. It offers openness. You are also guiding us to a notion of confrontation that is softer, perhaps without underlying violence.

YIOne backbone of this exhibition was our local market. I had been thinking about it when I came home in 2016. Our local, traditional farmer's market, which is also pre-colonial, is called the 'tamu'. It's an age-old farmer's marketplace.

Tamu means 'a meeting place'. The hill people, river people, jungle people, plains people, and sea people would meet here at this place, this tamu. The reason they meet is because people want what they don't have.

In other words, the intrinsic, fundamental point of meeting is to meet the other. The exchange that happens—rice for salt, salt for rice, and so on—shows that you meet precisely because one needs what one doesn't have. One needs diversity. One needs the person who is not from one's community.

The market is like a mat; like a platform or stage ready to be activated. For me, it was the motivation for this exhibition.

We have old foot-trodden pathways across mountains, now turned into roads, called 'salt trails', illustrating how important it was to meet the other. Coinciding with this exchange comes other social contracts: the exchange of knowledge and culture, of fighting and falling in love, of gossip and so on. Gossip is powerful.

This exhibition is the tamu. It is the coming together of all these things. I'm precisely interested in you because you are different, and you have something that I don't have.

RLMisunderstandings shape relationships. It is another threshold in exhibition-making and conflict, showing tensions and intentions to the world.

YII am working with inland people as well as sea people who generally have a strained relationship with each other. In Sabah, we have so much political prejudice about sea people. It's an age-old thing that dates back to the Sulu Sultanate that was hated in Sabah by the inland peoples for the imposition of unelected rule, such as the tolling of river mouths in trade, slave raids on land villages, and so on.

The continued insistence of the Philippines to not recognise Sabahans or to talk over Sabahans, and maintain a territorial claim on Sabah as if it's an empty piece of real estate for the taking, compounded with the Malaysia Federal Government's interference and manipulation of the Sabah demographic landscape, has exacerbated the local fear of the loss of sovereignty and forms of re-colonisation. The result is suspicion, conflict, and xenophobia towards people who come from the sea.

However, the old premise of our tamu markets, to meet and exchange, both illustrates the basis of our common social structure and perhaps shows a locally derived way forward. This has been foundational to me in the thinking of another way an exhibition can be structured. It can be organised around the notion of exchange, of gossip even, that comes from the participants and objects within the mat.

The market is like a mat; like a platform or stage ready to be activated. For me, it was the motivation for this exhibition. I am learning from other people's knowledges and experiences. The valuation is crucial: who you are selling to is who you are talking to.

I just want the museum to be more like a market, and more like a mat, in that true sense of an exchange of objects, knowledge, balance, and value systems: systems that are circular, restorative, and regenerative. I know it's there in museum studies, but I kind of lost touch with it.

Coming back home has been really foundational in recognising that space. It's the design of how people interact in a space, what they do in a space, how they do it, and who they do it with.

The banig of the Philippines are the same with tikar. I always say to people, 'You were probably, back in the day, made on a mat. Your parents made you on a mat. You were born on a mat. And when you die, you'll be buried, rolled up in a mat.' It's the skin you don't even think about, but it locates you somehow and is a museum of your biography.

RLI think you're also touching on the unruliness of relationships. The agonistic nature of relating with each other and maintaining these connections is a reality that is rarely discussed in curating art.

This mat is a social design, simulating the architectural in a space where we recognise how relationships explode, and how relationships can be bounded. If there's already too many of us in one square or rectangular space, you can go elsewhere or you can unite your mat with other banig or tikar.

It is not just knowledge about spaces or making space—it is also an intimate understanding of the sufficiency of what you can give and what you can take from other people. The gesture results in a scenography of public intimacies. It varies within the scale of relationships between the private and the public as well as with other identities.

The artistic impulse is recalibrated here only to find new attachments with the publicness of life, which in itself is artistic. I am curious how all these change your expectations.

YIWhen I was in Manila recently, I found out that the Tagalog word for table is mesa. In Malay, it is meja. The etymology of these words is interesting because the Tagalog mesa and the Malay meja come from the Portuguese and Spanish mesa.

Traditionally and historically, in pre-colonial times, when talking about the fundamental genetic memory of place, architecture, and social relations, we didn't have tables at all. What we had that might be considered as tables include a rehal, which is a stand to hold the Koran; the dulang, which are raised trays where you might have placed your betel nut set; and the pelamin, which is a raised stage where the bridal couple sit during traditional weddings.

The table represents colonial power—a kind of hard patriarchy. On the other hand, the mat remembers, more than anything else, a feminist, egalitarian community.

There were no tables. We sat and we did meetings and everything on the floor and ground on mats. Tables came in with other people. I did this series of artworks ('Picturing Power', 2013) where I was addressing the violence of administration represented by the table, specifically the colonial administration in census, land survey, education and so on, which all declare: 'I will tell you who you are'. I could've included the museum.

How were we colonised? Not through guns, but through the violence of administration, the sorting of data and value systems.

The table represents colonial power—a kind of hard patriarchy. On the other hand, the mat remembers, more than anything else, a feminist, egalitarian community. I'm involved in NGO and community work. It's very interesting how you organise yourself physically when you are working with the community.

If you're sitting at a table or on a mat, the entire dynamic changes. The table could, for example, now represent the education system dictated to us. We are taught Peninsular Malaysian history. We don't learn Bornean history.

I'm working with people living on the sea, and they have lived on the sea for centuries. They do not have identity cards or passports. They do not have paper identity at all. But they are rich with cultural identity. They are amazing weavers. All this knowledge is there, and it's in the mat. They have no identity according to the table.

RLThis relates to the formation and distribution of power and agency.

YIThe mat is about revelation, pointing to the relationship between the structures of power and exercising power. You can see the relationship of power on the mat. The more you know someone, the more you lean on them and the more likely you'll soon be lying on their lap. We all know that experience.

When you have a community meeting on a mat, there is no boss. You might have a leader, but that leader shares more than the other individuals. Male or female, they are both on the mat, but the dynamics is feminist and egalitarian. It communicates differently.

I'm very curious if it comes across in the exhibition, but it's fundamental as to why I'm working with mats. I think it does, because the very people making those mats are the holders of knowledge, storytelling, and culture that are incredibly rich. They don't go to museums, but their objects are collected and put into museums.

When you are actively taking control of your mat, you are innovating left, right, and centre. Mats have always been made before. We have been inventing objects. I want the exhibition to be alive, not ethnographic.

So how do you decolonise all of these aspects? How does the museum become more like a mat, as opposed to a table? I have all these hidden agendas that are not so hidden anymore because I talk about them all the time. I want to turn the tables on the museum. I want to replace the table with a mat.

If the world shifts from 'table power' to 'mat power', that is a seismic systemic shift. But within our region, it is not new. And that's the point—it is already known.

When I showed the two-sided mat Tikar-A-Gagah (meaning 'A Valiant Mat') made by Dusun and Murut weavers from inland Keningau and the Bajau Sama DiLaut community from the Sulu-Celebes Seas in the foyer of the National Gallery Singapore, one member of the museum's cleaning services saw it and started crying.

She asked, 'tepo?' Tepo is tikar or banig for the Bajau peoples. It was the first time she recognised something of her cultural identity in the museum that she cleans every day. And I thought, 'That's the point. I'm talking to the people.'

That's why I started working with mats. When the National Gallery Singapore through their OUTBOUND initiative invited me to make a work for one of their public spaces, of course, I had to try flip tables. You're totally inviting me to turn the tables.

I wanted to bring the mat because you bring a whole lot of Southeast Asia to that space. And I don't want it to be ethnographic. It's contemporary.

RLThe idea of aliveness and the promise of being alive within a museum are museological goals that have been left out. Other than colonial administration, some strategies of curatorial administration also colonise ideas, objects, and traditions. The possibilities of aliveness in a museum decompose our inheritance from modernity or other indoctrination to progress.

When you propose that the mat is our museum, it brings us outside of the museum and delivers us to a museum that is our vicinity, in all that surrounds us. We have been detached from museums and exhibitions as emotional spaces. Aliveness and emotionality coalesce diverse experiences of seeing and feeling.

I think it is a more generous language to discuss art produced and presented in places away from self-styled art centres. The two-sided mat inevitably proposes a form for a more accessible museum through its modularity, portability, and diversity.

Could you share your thoughts on these promising functions of the mat in museology and in the larger infrastructure of caring for art and heritage?

YIIt's the precious object that all life has been taken away from the museum. I tried to show people how much life there is in the object that is actively engaged with contemporary times. There is no separation from the judgement that comes onto it. There are also linguistic threads going through all these works. The language that comes with the mats captures me all the time.

The mat is multigenerational and multilingual. I feel like the language of much museology can be monolingual, and the canon it serves works akin to monocropping.

If the museum behaves like a table and is extractive in the capitalist sense, maybe the mat and its tamu promotes circular economies fundamentally based on restorative and regenerative principles. How might that take form in the story of art and the placemaking of a museum or where and why we might commune and meet and what story is told in exchange?

Ideas of 'progress' have changed dramatically since 2020. What really is the avantgarde aka the front-liner of culture? I'll tell a story to illustrate.

The Bajau Sama DiLaut sea people live on the border between the Sulu Sea and the Celebes Sea. This is part of the Coral Triangle, which contains 76 percent of the world's coral species.

This Coral Triangle is vital for our ocean life. Communities of sea peoples primarily make money from fishing. Before the pandemic, Mainland Chinese tourists swamped Sabah by the thousands.

RLTell me more about this and how it affects the community of weavers.

YIThe stateless women I work with used to primarily make income for their domestic economies by helping their husbands fish. Now we have a small industry of weavers working at home, caring for their children, teaching their children heritage weaving knowledge and not fishing.

When they are not fishing, another lobster lives another day. It's a very, very small thing. But if it is multiplied in ways that allow other women or communities to find alternative livelihoods, it has a direct, contemporary impact on global issues such as climate change, sea health, and marine life.

The Coral Triangle is a spawning site. Every time someone plants pandanus (screwpines) along denuded coastlines, they are planting the material that we will work with and they are protecting this fragile environment.

Weaving is tremendously conceptual because it is fundamentally mathematical and precise. The historic traditions that it originates from are also conceptual, with coded linguistic rhythms shared amongst women, and this language is full of ideas reflecting the community's worldviews.

We don't work with plastic. We are working with mostly natural materials. Weavers are no longer working the sea. They are not being extractive, they are behaving in a regenerative and restorative manner; environmentally, culturally and socially.

During Covid, when there was no tourism, no seafood restaurants were open. When there were no jobs, husbands were helping their wives with weaving. Because they were sharing time together, women were teaching their children and families their rich cultural knowledge. The Borneo Heart exhibition was woven during the pandemic.

This is direct engagement with an entire community of people who are front-liners of a globally significant tipping point ecology in the age of climate change, whilst also connecting to gender issues and domestic and circular economies.

The weavers are raising their own funds to build what we have nicknamed 'Balai Bikin', a 'making hall'. We are exploring ways of making an economy, a sovereignty that works for us.

I had this agenda to make art and to make an art show, but it's these tributaries that came out—making, inventing, thinking, and organising with the weavers—that I'm so enamored by.

Borneo is such an ecologically and culturally vital place, and discussion of systemic shifts, whether environmental, political, or social, needs to come from within households. And this has to be taken collectively.

That is progress because it includes re-ordering knowledges and relationships, ideas and objects. Somewhere in all this is an avantgarde museum, a platform and stage that is also a mat calling people to commune in a more equitable manner, inviting activation, a meeting place for exchange to find what you don't have.

If the world shifts from 'table power' to 'mat power', that is a seismic systemic shift. But within our region, it is not new. And that's the point—it is already known. Anyway, it has all been a revelation for me.

RLThese tributaries connect us to the grid of artistic task and intention, which have been demoted or made insecure during the pandemic. The confidence in artistic agency is in crisis. This might sound religious, but faith and trust in the artistic reproduce affinities. It's a nest that takes care of and carries the world within its own boundaries. Within this economy, the artistic intention actually meets other economies of desires.

Another question I have for you has something to do with the proof of concept in creativity. How do you resolve that? Is there a need to defend that as a contemporary artist working with different manifestations of conceptualism?

YIProof of concept is quite clear amongst us. It's like a rhythm. Mats contain rhythms, counting patterns that come from mum, grandma, ancestors. Weavers are always adding to these old rhythms with their own flavours. I'm doing the same, adding or expanding rhythms. Weavers will likely also take my rhythms and add to these, in a constant relay.

We talk through ideas and intentions a lot, but it is clear what my rhythms are and what theirs are. What is left in question are economic issues—that's why economic systems have become so important to me.

What is the value of regenerative and restorative circular economic sovereignty? How can we make this grow and take life forms and be sustainable and become like another mat, an economic mat? All of the above has been about looking for rhythms with a beat that everyone benefits from; a pulse, a Borneo Heart.

Weaving is tremendously conceptual because it is fundamentally mathematical and precise. The historic traditions that it originates from are also conceptual, with coded linguistic rhythms shared amongst women, and this language is full of ideas reflecting the community's worldviews.

The problem is that a lot of people looking at it are not able to access the conceptual thinking because they haven't been educated so there's a tendency to look for an abstract pattern derived from something that they can recognise.

I think it's the same with a lot of old community knowledge. I'll give you the example I've used a lot in trying to describe this not-knowing. In 2018, I 'instructed' our first test mat to see whether we could work together. It was supposed to be a basic exercise, a mat, five by seven feet in size. The size came back wrong. I arrogantly thought, 'Oh, they don't take instruction well.'

Then I realised they're alphabet 'illiterate' and don't use feet and inches. I wasn't listening, I was acting like a table and wasn't on the mat. They use their body and rhythms to measure, which is a multigenerational and multilingual approach. I was being 'monolingual' in my rhythms.

The mat is measured with the designated weaver's foot. It is performative. She puts her foot down on the edge of the mat and she shouts, 'allom!', which means 'life' in Bajau. The first step that she makes declares life for the mat.

For the second step, she lines up the heel to the first foot's toes and declares 'amatai' which means 'death'. Balance must always be sought. She continues along the edge of the mat making another 'life' step, then another 'death' step. The measure of a mat must start on life and must end on life.

The rhythm is corporeal; a dance. The conduit is a physical weaver's body that remembers the old knowledges, mother tongues, muscle memory, mnemonic counting patterns, and stories.

She is the nominated and designated body to represent the other bodies present, but listen to the rhythms and soon the multigenerational and multilingual becomes very tangible. The weaver walks life across the edge of a mat. I am humbled by the beauty of that thinking. —[O]