Hana Miletić: Patterns of Thrift

In Partnership with The Approach

Hana Miletić. Photo: Bea Borgers (Kunstenfestivaldesarts).

Hana Miletić. Photo: Bea Borgers (Kunstenfestivaldesarts).

Born in Zagreb, Croatia, and now based in Brussels, Hana Miletić's practice revolves around the act of weaving, which for her culminates in an effect that is both material and metaphorical.

She uses weaving as a gesture of care and repair to reflect on issues relating to social reproduction and ecology.

For her exhibition Patterns of Thrift at The approach in London (7 May–26 June 2021), Miletić took inspiration from the history of the gallery's local area in Bethnal Green, which developed as a site for silk weaving from around the mid-17th century before its slow erosion and eventual disappearance in the 20th century.

The works in the show are part of her ongoing series 'Materials' (2015–ongoing). For these pieces, Miletić begins with a photograph, taken by her, of acts of repair in urban space—perhaps of a broken window or damaged car wing mirror—and recreates these through a process of hand weaving textiles to match the colour, shape, and scale of the original repair. A collection of 'Materials' are also on view at Bergen Kunsthall, where Miletić's solo exhibition Patchy opened on 27 May 2021 and runs until 15 August 2021.

Included is the large-scale woven work Materials – Arena, Pula (2019–2020), for which Miletić replicated the covering of a window of the former Arena Fashion Knitwear factory in Pula, Croatia, that she photographed in 2019, using hand-woven and hand-knit textile with repurposed knitwear. Covering two former windows of the Bergen Kunsthall, the work echoes the factory's collapse, acknowledging the impact that this had on its labourers.

In this conversation, Miletić joins Diana Campbell Betancourt, the Founding Artistic Director of the Samdani Art Foundation and Chief Curator of the Dhaka Art Summit, to discuss textiles as carriers of migrating connections, engaging the ancestral practice of weaving to relate manifold matters such as care, repair, labour, and multispecies collaboration.

During the conversation, Betancourt and Miletić ruminate more specifically on some examples of the non-violent harvesting of silk in an attempt to answer the question: in a market economy, how is it possible to behave like the living world is an invaluable gift?

DCBWe come from very different parts of the world, but we share a passion for thinking about and feeling the world through weaving. To start, maybe we can talk about patterns migrating, and look more specifically at the context where The approach is located.

HMFor this exhibition, I investigated the history of silk weavers in the gallery's neighbourhood, Bethnal Green. I was looking for ways to ground the works in times when travel is restricted.

The works are all based on repairs that I photograph in public space and then reproduce through weaving. What I would ideally have liked to do is photograph the neighbourhood and then make works based on these photographs.

But as travel has been impossible over the last year, I grounded the works through the history of the neighbourhood where silk weaving was happening from the mid-17th century through the beginning of the 20th century. It was also activated by Huguenot refugees from France, who joined the silk weaving industry in East London.

The idea of living and dying together on a damaged earth really resonated with me while making this exhibition and weaving these works using non-violent and repurposed silk, which I then had to untangle to weave or use as raw fibres.

The title of the show, Patterns of Thrift, comes from a quote about these migrant workers, and serves as an acknowledgement for the circulations of ideas and forms across space and time, and how textiles carry these stories.

Some of the research images that I was looking at when preparing the show include historical photographs from 1841, of cottages of silk weavers in Bethnal Green, or drawings depicting female Huguenots; silk weavers preparing silk threads for warping the loom, as well as the actual weaving activity going on.

At that time, silk weavers in the neighbourhood were mainly making ribbons and decorative elements that were used in the luxury industry. They were producing half silks, meaning that they were using silk as warp threads, mixed with other fibres and materials as weft.

I was really drawn to the shapes of these ribbons, which I connect to very easily in relation to the work that I do that reproduces repairs, often using tape. Also, I was already making half silks of sorts, mixing threads from the economy and ecology of my studio to work in a more ethical and also more sustainable way.

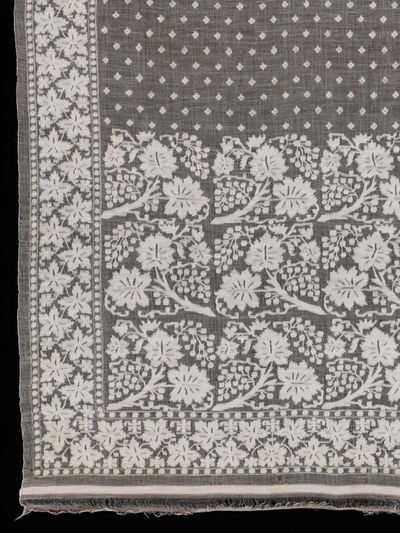

The objects I was looking at when preparing the show all come from the Victoria & Albert Museum's textile and fashion collection: an embossed ribbon of woven silk and flattened silver wire from 1855; a belt with a woven brass ribbon from the late 1900s, and a folding needle case from 1760, which is woven in gold silk.

The shapes of my works come from the repairs that I reproduce from public space, but I think it's kind of remarkable that there are also formal resemblances with the objects that I just mentioned. I hand-weaved half silks for this exhibition, in which I used silk threads, mainly repurposed from sustainable resources.

For instance, within the 'Materials' series (2020), there is a hand-woven textile using gold eri silk, gold metal yarn, and organic hemp to replicate brownish and beige tapes that I photographed on a car wing mirror, and another that uses copper metal yarn, gold eri silk, gold metal yarn, gold-painted recycled wood fibre, old gold metal yarn, organic hemp, pale gold recycled polyamide, and variegated gold organic cotton cord to replicate a repair of a broken shop window.

You can see how the half silks I wove contain silk fibres, but they also contain recycled wood fibres or repurposed polyester threads, amongst others, so there is a variety of different materials.

I also learnt that the weavers' activities stopped because of automation. This was a result of the invention of the Jacquard loom, which was a forerunner of the present-day computer. So for the works in this exhibition, I included patches of automated fabric.

For the bigger works in the exhibition, different elements were assembled using photographs as backdrops, drawing parallels to the usage of 'cartoons': drawings on hard paper or cardboard in 16th- and 17th-century tapestry.

While preparing for this conversation with Diana, I also looked at ribbons and textiles from South and Southeast Asia that were produced at the same time as when the silk weavers were active in Bethnal Green, and which were also brought to London in the period that they were still active in the neighbourhood.

My thinking of what care and repair mean not only happens formally through reproducing repairs that I find in public spaces, but also thinking about what a multi-species collaboration could look like, when figuring out how to how to work with silk.

The Victoria & Albert Museum Collection has, for example, silver gilded ribbon from Delhi from 1855, which was brought to London in 1879 by the East India Company as part of the Indian Museum collection, which no longer exists. Its collection was dispersed into different institutions, like the V&A. I want to raise this as it ties into Diana's experience working at the Dhaka Art Summit, particularly the exhibition A beast, a god, and a line.

DCBA beast, a god, and a line was curated by Cosmin Costinas for Dhaka Art Summit 2018, who is a brilliant curator and the director of Para Site in Hong Kong.

This show began when I noticed the presence of regional silos getting in the way of much needed exchange between South and Southeast Asia. As you know, there are different definitions of South Asia. The Harvard definition positions Afghanistan to the West and Myanmar to the East. Other definitions do not include Myanmar. Some include Iran. It's nebulous and in my opinion too limiting of a framework to use externally imposed geographic definitions to understand the complexities of Bangladesh.

When this show started to come about, we were amid the Rohingya crisis. The Muslims in Myanmar—who Myanmar did not want to recognise, who the military was massacring in the south, and who had lived on the land for centuries—were fleeing into Bangladesh, risking their lives in the process.

Many cultures, including the Rohingya culture, predate the political border lines of modern-day nations. And one way to see that is with textiles. Politics can change, religions can change, and languages can change, but weaving patterns change far more slowly. This is something Cosmin talks about in his curatorial practice.

If you start looking at weaving patterns of certain indigenous communities across India, Bangladesh, Nepal, Myanmar, and Thailand, you can see some similarities, especially with backstrap weaving. Backstrap weaving employs a very portable loom that can be picked up and taken with you if ever you have to migrate.

It's interesting to think about DNA as a form of weaving as well. A beast, a god, and a line shows that textiles can carry these codes that perhaps oppressive regimes want to wipe out. The exhibition grew and morphed and brought in different narratives of other socio-political phenomena weaving their way into the region, such as politicised religion. The exhibition travelled from Bangladesh to Hong Kong, Myanmar, Poland, Norway, and then to Thailand.

My mother comes from an island called Guam, which is a U.S. territory, that is less than a four-hour flight from the Philippines or from Japan. It is nowhere near the continent of the United States.

Because of tropical weather and climate change, a lot of objects don't survive, but my mother would tell me that the treasure of the object was knowing how to make it. And we'll get into this a bit later.

A lot of weaving techniques in South Asia were destroyed with the advent of the Industrial Revolution, not just because of the loss of techniques, but also the extinction of crops that were used to weave these textiles.

Taloi Havini, who showed in the last Dhaka Art Summit is from Bougainville, an island area near Papua New Guinea, spoke to me about how her community would destroy certain structures to have the people weave them again, to make sure that that knowledge was transferred and known and carried forward.

I know you're a carrier of weaving history, so I thought it would be interesting to talk about muscle memory in relation to your practice.

HMThank you so much for brining in the topic of muscle memory. The practice of weaving runs in my family history, but it's something that I have only learnt about fairly recently.

My maternal great-grandmother was involved in a weaving community. She would go around people's houses in her village and help them set up and warp their looms. But this is family history, which I only know through stories and through a few cloths that we have in the family; I'm not even sure if she wove these herself or they were gifted to her, or whether she was perhaps paid with them.

The weaving practice skipped two generations, with my grandparents moving from the countryside to the city and my parents and myself migrating to Belgium in the 1990s due to the Yugoslav Wars. I unfortunately don't have any images of my great grandmother's textiles, but what I do have are film stills from a short documentary called The Best Husband.

Once world-building happens, repair is a practice that is invisible. Understanding how repairs are made by reproducing them is a way to figure out how to contribute towards that transition or transformation.

It's a documentary from 1968, which shows the activities of a female-led weaving cooperative in Serbia on the border with present-day Bosnia and Herzegovina, which I have shown in the context of previous exhibitions (Mistik, La Loge, Brussels, 23 January–27 February 2021) and that will also be screened next week in the context of my exhibition at Bergen Kunsthall, which just opened.

In retrospect, learning how to weave allowed me to find other ways to deal with reproduction in my photography practice that I was struggling with—I was able to slow down and situate the photography. But, maybe even more importantly, I learnt how to weave to trace the patterns of the work that my maternal great-grandmother was doing in her village.

I was able to tap into some muscle memory to do so. One picture from our family album sees my maternal grandmother, my niece, and myself playing with raw wool to use for hand work. For me, it's an emblematic image of tapping into ancestral knowledge and weaving as a living and embodied craft, recalling the muscle memory to weave.

DCBYou talk about care and repair, and you alluded to this with silk. But you're also using repurposed silk, and maybe something that doesn't come to people's minds immediately is the amount of death that is involved in any silk cloth.

Most silk involves silkworms being boiled alive inside their cocoons. And one of my favourite songs that references this is a 1978 song by The Human League called 'Being Boiled'. And I love this particular line, 'Boiled alive for some God's stocking'.

The designer Neri Oxman created these robots that co-create architectural silk pavilions along with silkworms, which seems humane, because no silkworm needs to die in the creation of silk. When it comes to labour and exploitation, one question that comes to mind is whether it is better to be worked to death, or boiled alive?

HMI think that the topic of labour is always present when talking about textiles, because textiles labour has always been central to histories of capitalism and to resistance against ruthless systems of production. In the 21st century, I think the feminisation and devaluation of globalised and outsourced labour in textile industries is an important consideration to always keep in mind.

Another one would be the silkworms that are also exploited workers of sorts. In the making of the show, I was struggling with the notion of working with silk for the same reason as Diana explained—that the silkworm is basically boiled to death for their cocoon to be used for commercial silk. I learnt about a non-violent silk, where the caterpillar can fly off after the process. But even this solution becomes sticky, because one hears stories of insects being too overworked to fly. They're basically exhausted labourers.

I think that Donna Haraway's notion of 'staying with the trouble' applies here. The idea of living and dying together on a damaged earth really resonated with me while making this exhibition and weaving these works using non-violent and repurposed silk, which I then had to untangle to weave or use as raw fibres.

My thinking of what care and repair mean not only happens formally through reproducing repairs that I find in public spaces, but also thinking about what a multi-species collaboration could look like, when figuring out how to how to work with silk.

DCBWhen we talk about repair, I think you're also considering how not to add more violence into the world. How do you use what's already there to try to heal it? And maybe we can transition into your ideas around how we postpone the end of the world?

HMTotally. I think this is kind of where my main interest in repair comes from, because it's a practice within a larger practice of care.

I'm interested in care because it's in our lives at all levels. It's in our intimate relationships as well as our relationships to the planet.

In a very generic way, caring can be viewed as a species activity that includes everything to maintain, continue, and repair the world to live in it as well as possible. This includes human bodies and the environment, all entangled together.

For me, repair is a really important practice within that larger activity of care. Once world-building happens, repair is a practice that is invisible. Understanding how repairs are made by reproducing them is a way to figure out how to contribute towards that transition or transformation.

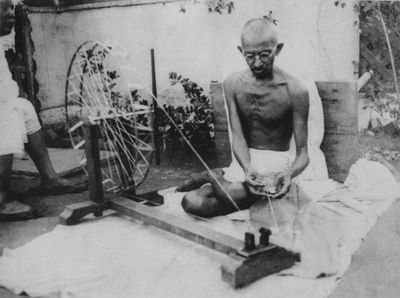

DCBI saw you had those images of Gandhi and these South Asian textiles. When we look at Gandhi, we also have to think about the religion-based violence that came along with the independence of British India; Gandhi's legacy cannot be seen as one of pure peace as it is turned to in order to justify policies that exclude Muslims.

My friend Bandana Tewari often writes and speaks about Gandhi and his commitment to Indian and South Asian independence through his sartorial choices. She writes, 'Gandhi saw a manifestation of colonial hegemony in the "machinery" that made India dependent on foreign factories to produce its clothes, which went against his deep belief in Swadeshi, or economic self-reliance. He therefore initiated the khadi movement, which sought a nationwide ban on clothes made in the mills of Britain. Galvanising Indians to instead pick up the humble spinning wheel and weave their own khadi.'

This ability to weave by oneself was an attempt to throw off the shackles of colonial oppression. It was a gesture designed to curb the power of the garment industry that was bound up with oppression and still is today. We see this now in Bangladesh, where the garment industry is one of the main sources of export income for the country.

While Bangladesh is under lockdown, the garment factory workers are going to work because the country needs it. But for us as consumers, we need think of repair and care. Another friend Imran Amed asks a pointed question of why and how a garment should cost less than a sandwich? We're also implicated in this exploitation when we look at the voting power of our money.

This is where there's something charged about caring: do we care about the invisible people making our clothes, the invisible silkworms that are dying for our luxury garments? Maybe you could talk a bit about the idea of care and relationships in relation to the planet and other species in your work.

HMI'm interested in care because it's in our lives at all levels. It's in our intimate relationships as well as our relationships to the planet.

My interest also stems from a longer-running engagement with care and reproductive work that comes from growing up in a matriarchal, communal setting in former Yugoslavia. I want to find ways to get in touch with that and figure out what kind of politics would serve or provide for that.

Going back to repairing colonialism, 'The Care Manifesto' by The Care Collective, which I came across recently, sums up all the different tentacles of care work that seem so timely and necessary, and which tie together two different threads that we are discussing.

It states that universal care will reclaim 'all forms of genuinely collective and communal life, adopting alternatives to capitalist markets, and reversing the marketisation of care and care infrastructures.' I think this really taps into what you were just saying about the fast fashion industry.

But we can also think about it in terms of deepening a welfare state's restoring of care infrastructures. The pandemic has showed how destroyed some of those infrastructures are. It should also include porous borders and radical cosmopolitan policies of conviviality that address climate change at a transnational level, as well as an expansive model of kinship, beyond the nuclear family model.

This is the care politics that I want to think with, sit with, and work for. The remaking of the repairs is a way to find a practice within that thinking or within that politics.

DCBLet's transition from politics to poetry, which are of course linked, and turn back to some of the reference images you were showing from Bangladesh. Some of these images are of muslin cloth, a fabric that, sadly, is now extinct. You can enjoy them in museums, but it was a cloth whose excess of six yards of length could pass through a ring—a feat that would prove this 'woven air' as genuine.

This is an excerpt from one of my favourite poems by a late exiled Kashmiri poet named Agha Shahid Ali called 'The Dacca Gauzes', and it references that beautiful muslin cloth:

I think this poem beautifully describes the mix of body memory, violence, and how these colonial histories are so woven into each other.

And maybe something else to share here is that jamdani—muslin—as it was cannot be made today, partly because the fibre is extinct, and if you were to buy jamdani made with a different fibre today, it is expensive. Because of the economics of the garment industry, some forms of weaving are being pushed into a vulnerable space.

DCBThis poem inspires a body of work by Daniel Steegmann Mangrané developed for the Dhaka Art Summit and also a main character in an unrealised exhibition proposal I developed with Iaroslav Volovod and Raimundas Malašauskas, and it primes a lot of my curatorial thinking about embodied memory in the wake of trauma.

Hana, do you want to share the poem that inspires a lot of your work?

HMMy poem offering for today is by Cecilia Vicuña, called 'The Glove', which accompanies a performance. I wanted to bring it in because it voices the transfer of ancestral knowledge, and also evokes what a multi-species collaboration could be.

The poem goes: 'During a bus ride I would raise a hand gloved in a glove beloved / the glove is not a glove, but a primordial mythic being. / When a girl is born, her mother puts a spider in her hand, to teach her how to weave.'

I think it's really beautiful to acknowledge spiders as the first teachers of weaving. And, by the way, spiders can also produce silk, although this is not something that is used commercially. One of the things that Diana and I were speaking about when preparing this talk is the idea of a gift and the invaluable gifts that we are blessed with.

What if we were to consider spiders as weaving teachers, and silk threads and fibres as gifts from the earth that establish a particular relationship or an obligation of sorts? To give and to receive, but also to reciprocate? I think it is possible to consider, even in a market economy, how to behave as if the living world were a gift.

There's this wonderful quote by Robin Wall Kimmerer, who wrote the book Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants (2013), which goes as follows:

'What would it be like, I wondered, to live with that heightened sensitivity to the lives given for ours? To consider the tree in the Kleenex, the algae in the toothpaste, the oaks in the floor, the grapes in the wine; to follow back the thread of life in everything and pay it respect? Once you start, it's hard to stop, and you begin to feel yourself awash in gifts.' —[O]