Natalie Rudd on Breaking the Mould: Sculpture by Women Since 1945

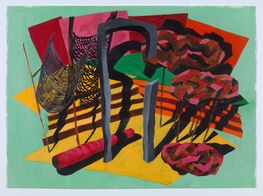

Courtesy Natalie Rudd.

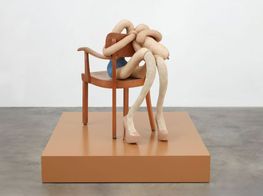

Courtesy Natalie Rudd.

In her role as Senior Curator of the Arts Council Collection, Natalie Rudd is overseeing the upcoming touring exhibition, Breaking the Mould: Sculpture by Women Since 1945 (29 May 2021–12 March 2023).

Drawing from the Collection's holdings, Breaking the Mould will begin at Longside Gallery in the Yorkshire Sculpture Park, where the Arts Council Collection's sculptures are managed and reside, before it moves on to Djanogly Art Gallery and Lakeside Arts in Nottingham, New Art Gallery in Walsall, Ferens Art Gallery in Hull, and The Levinsky Gallery at the University of Plymouth.

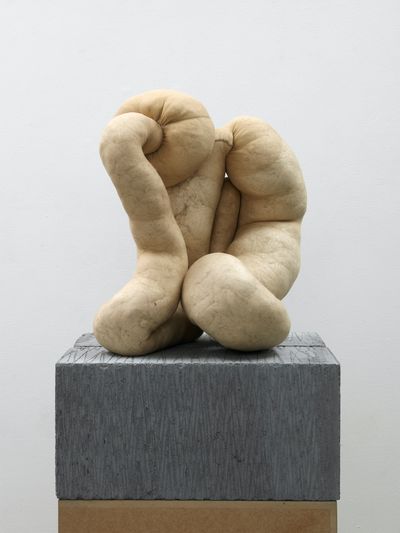

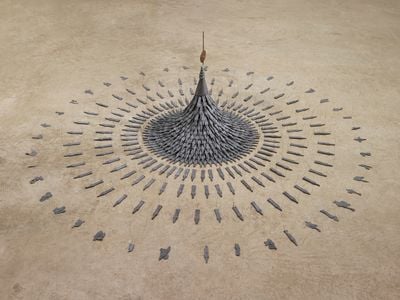

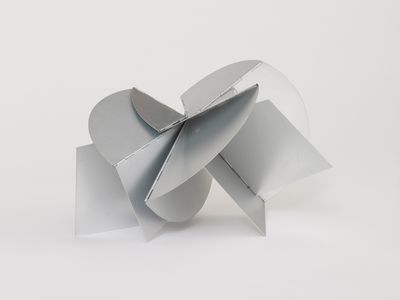

Including work by over 40 sculptors, such as Kim Lim, Jann Haworth, Cathy De Monchaux, Mary Kelly, Helen Chadwick, Rana Begum, and Holly Hendry, to name a few, the exhibition draws on the Collection's historical trajectory, from its founding in 1946 to the present day.

The earliest work is Barbara Hepworth's Reconstruction (1947)—one of among approximately 80 drawings that the artist created in an operation theatre, transferring her observations of surgical proceedings into celestial scenes rendered in pastel hues. Since this early acquisition, the Collection has expanded to include a variety of practices that embody an acquisitions process that is defined by 'a spirit of risk taking', as described on the Arts Council Collection's website, and reflected in this exhibition through materials that are often transient and ephemeral.

In Phyllida Barlow's untitled: dunce (2015), for instance, yellow paper spills from beneath an upturned bucket on a stack of cement, plaster, and polyurethane, while more discreet works such as Hair Bonnet (1997) by Kathy Prendergast features human hair, painstakingly mounted as a tiny a bonnet.

Such materials hold resonance in the present moment, with the exhibition having been postponed as a result of the pandemic. Drawing on themes of resilience and perseverance while reflecting challenges experienced by women artists, Breaking the Mould hopes to open new fields for exploring such challenges through voices from across generations. The project departs from a research project by Catherine George (Associate Dean for Quality and Accreditation, Faculty of Arts and Humanities, Coventry University) and independent curator Hilary Gresty, titled Women Working in Sculpture from 1960 to the Present Day: Towards a New Lexicon.

In this discussion, Rudd expands on the themes explored in the exhibition, and the Collection's latest concerns following upheavals of the last year, providing insight into some of the highlights within the show's broader programming.

TMBreaking the Mould departs from a research project by Catherine George and Hilary Gresty, titled Women Working in Sculpture from 1960 to the Present Day: Towards a New Lexicon. Could you talk about how that lexicon transferred to the exhibition? What are some of the themes that thread through, beyond the overarching focus on work created by women?

NRI would see it as a project that runs in tandem with Catherine and Hilary's, with points of contact. Essentially, they received funding from the Henry Moore Foundation to interview approximately 30 artists from different career stages, and to really reflect on the experiences that they have had working as sculptors.

One of the interesting things that emerged was this kind of intergenerational cycle of experience, including these patterns and moments where they've hit resistance; moments where they have had to rethink and reconsider their direction; issues around parenting; issues around sustaining their career long-term, but also working as older artists and keeping things going for a longer time frame, juggling childcare with demands of the commercial sector, and so on.

Many of the artists that they interviewed we included in the exhibition, and many shared themes began to emerge when we started to do our research around it. We could see that there were points of chime and comparison. We were prompted to think about their research in relationship with our collections, and then the exhibition has grown and grown.

TMIt's interesting that the seed of this exhibition originated externally. How important is external dialogue to the long-term programming of the Arts Council Collection?

NRIt's always really important to keep a fresh and open view of programming, so we're always open to contributions, collaborations, and inviting external selectors to curate exhibitions from us. We've done this for a number of years.

We've invited a number of artists to select exhibitions from the Arts Council Collection, including Grayson Perry and Ryan Gander. We've also worked with specialists in the field, such as our 2014 exhibition Uncommon Ground: Land Art in Britain 1966–1979, which was curated by Nicholas Alfrey, Joy Sleeman, and Ben Tufnell.

This project kind of fits into that mould, but I think it's really important to say that it's not just about the selectors, but also our tour partners. We're not just making an exhibition that somehow magically fits into their programmes—there's a dialogue to which they can contribute. The selection for Breaking the Mould was a collective conversation between ourselves, Katherine, and Hilary, but also our tour partners, and it was really exciting to work in that way.

In taking risks, it's really important to learn from mistakes and to learn as a reflection, and I think that this is part of Breaking the Mould.

We're also trying to challenge what the notion of specialism means. Increasingly, we're looking to curate with communities, and especially with our National Partners Programme, we've really built on this area in the last few years, thinking about who selects and who gets to choose.

TMOn the website, the Collection's acquisitions process is described as being characterised by 'a spirit of risk taking'. This is reflected in the inclusion of Barbara Hepworth's drawing Reconstruction (1947)—the first artwork by a sculptor acquired by the Arts Council Collection.

The choice of a drawing over a sculpture reflected a 'loan collection in its infancy', as the catalogue notes. Could elaborate on what defines risk taking in the Collection today?

NRThe Arts Council Collection has often invested in artists at an early stage of their careers. We have a certain amount of money per year, and it feels fairer to spread that as widely as possible rather than buying one or two things, but invariably, when investing in the work of an artist at an earlier stage of their career, there's an element of risk about that.

It's also about knowledge. Our acquisitions committee are invested in contemporary art, so they visit a lot of artists' studios, and they know what's going on—they can see potential.

That spirit of risk taking is important to ensure that we're being relevant with our acquisitions but also our programmes. For me, I think risk taking is about being bold in our programming, making sure that we're asking questions that are relevant across society and with lots of different groups, not just sitting in an art world niche.

In taking risks, it's really important to learn from mistakes and to learn as a reflection, and I think that this is part of Breaking the Mould—we're putting something out there and we hope that it provokes a conversation, but we also want to learn from that so that we can channel that into our future programmes.

TMI understand that the Arts Council Collection is predominantly led by women. Could you discuss what efforts are being made to consider intersections of race and class within the Collection?

NRThe interesting thing about this exhibition having been postponed for a year is that it's now our 75th anniversary, which makes it even more of an important moment to reflect on our history.

You're absolutely right—apart from our directors at Arts Council England, the designated heads of the Collection have always been women, which I think is a really interesting fact. There have also been very influential women at the Collection, such as Marjorie Althorpe-Guyton, who directed and informed our programmes over the years.

Last September, Deborah Smith started as our new director. It's an exciting moment, because we're starting to think about diversity and representation across all of our programmes. Breaking the Mould is an important part of that project, but you'll also see with our national partners exhibitions, it's really determined the programming, which is much more inclusive and ensures that the breadth of our exhibitions is visible.

There is a lot of work going on behind the scenes. We've also got a very fruitful partnership with UAL's Decolonising Arts Institute, headed up by Dr susan pui san lok. We're just on the cusp of launching a new Decolonising Collections: Curatorial Research Network, funded by the Art Fund, and it will involve three researchers working with the Arts Council Collection, British Council Collection, and Manchester Art Gallery, to look at our Collection through a decolonising lens, to unpick the processes we may have assumed and learnt over the years, to try and look at our collections with a fresh view.

We're really excited, not just to look at this process ourselves, but to have external researchers come in to reflect on our holdings and our processes.

TMHas the exhibition format for Breaking The Mould changed in the time it's been postponed? Or will it continue as planned?

NRThe structure hasn't changed, but I think what it has enabled is greater anticipation. With world events and the pandemic, I think there's been an even stronger desire for this exhibition, and an opportunity for us to look at what women have done in the field of sculpture. It's really exciting, and having a chance to install the exhibition in light of everything that's happened over the last year makes the exhibition even more in the present.

TMWhat efforts is the Arts Council Collection taking to engage non-specialist audiences across these different locations?

NRThere will be a difference in size as the exhibition tours, because the venues are different sizes. Some venues have their own collections, so the Ferens Art Gallery in Hull and The New Art Gallery in Walsall both have amazing collections, and it's hoped that there might be relevant works brought out of those collections for the exhibition.

With world events and the pandemic, I think there's been an even stronger desire for this exhibition, and an opportunity for us to look at what women have done in the field of sculpture.

At Nottingham, there will be a conference in December, where we will invite speakers, specialists, and artists to reflect on the subject, in the middle of the exhibition's tour. But in terms of non-specialist audiences, there's loads going on. Many of the interpretive labels are written by non-specialist voices, including previous interns or participants of local community groups who have reflected on the work.

We've made a teacher's pack, which is made with teachers for teachers, and we've tested some of the activities with home learners, because we couldn't go into schools. There is a fantastic resource room, which features an interactive timeline, so you can add your own personal or special date in that developing response to national events.

TMI noticed in the catalogue that there is an emphasis on ephemerality and transience in a lot of the works in the exhibition. How do those aspects feature in the spirit of risk taking we were discussing earlier? What challenges do they pose in the touring of the exhibition?

NRA lot of thought goes into how we care for works long-term. Our acquisitions committee have taken risks with ensuring the most innovative work is acquired, which has often meant that works are inherently perishable. So it's not just about very careful packing and display and invigilation, but also long-term solutions for the care of those works.

In some cases, that's just about having a really close dialogue with the artist about which materials can and can't be changed or replaced. Sometimes it's very specific. For example, Phyllida Barlow's work features paper, and we know exactly what that paper is so that we can create it again. In some cases, we've got very specific manuals; it's not just a set of instructions, it's more like a book, so we've got a recipe book for the future but also the present.

TMIs there a work that you're most fond of in the exhibition?

NRThis touches on your last question—I think the works that really chime with me are those that play with ideas of vulnerability and perishability. For example, Anya Gallaccio's can love remember the question and the answer (2003), where red gerbera placed between windowpanes of two mahogany doors disintegrate over time, reflecting on thoughts around mortality and beauty and so on.

I think that comes from women's experiences dealing with art schools and the art world, and I think it plays out in this perishability—dying flowers, things that have been salvaged, lost and found things, and that some artists have looked at this idea of vulnerability and turned it into a strength, and I find that really inspiring. One of the strong themes of the show is resilience and perseverance. —[O]