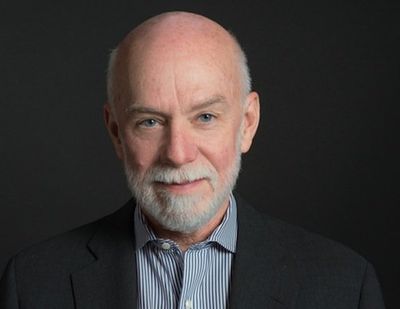

Richard Armstrong

Richard Armstrong is the Director of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and Foundation.

As well as managing the foundation he oversees the Guggenheim Museum in New York as well as the Peggy Guggenheim collection in Venice, the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, the Deutsche Guggenheim and the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi due for completion in 2017. Prior to this position, he was the Henry J. Heinz II director of the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh, where he had also served as Chief Curator.

From 1981 to 1992, Armstrong was a curator at the Whitney Museum of American Art, where he organised four Whitney Biennials, as well as important exhibitions such as a Richard Artschwager retrospective and The New Sculpture 1965–75. In 1980, he served on the Artists Committee to organise the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA), Los Angeles.

Armstrong also serves in an advisory capacity on a number of foundation boards, including the Victor Pinchuk Foundation, Kiev, Ukraine; the Artistic Council, Fondation Beyeler, Basel; the Al Held Foundation, New York; the Judd Foundation; and as Director, Fine Family Foundation, Pittsburgh. Armstrong is also a member of the Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD).

Anna Dickie spoke to Richard Armstrong on the day that No Country: Contemporary Art for South and Southeast Asia, the inaugural exhibition of the Guggenheim UBS MAP Global Art Initiative, opened at the Asia Society in Hong Kong. The Initiative is a multi-year collaboration that will chart contemporary art in three geographic regions—South and Southeast Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East and North Africa.

Organised by June Yap, the Guggenheim UBS MAP Curator, South and Southeast Asia, the exhibition focuses on the artistic practices and cultural traditions of the region which includes Vietnam, Cambodia, Thailand, Indonesia, Singapore, Malaysia, the Philippines, Myanmar, Bangladesh, and India. The exhibition in Hong Kong follows its presentation in New York and precedes its final iteration in Singapore. The art works in the exhibition, along with others acquired from Guggenheim UBS MAP, will be included in the Guggenheim's permanent collection.

However, our definition of 'world' has so far been largely Europe and America. That is changing even today as we go to the Middle East. So there is one strategy.

ADThe Guggenheim has set itself the task of being a 'global art museum'—with physical spaces in Bilbao, Venice and soon Abu Dhabi. Now, via the Guggenheim UBS MAP Global Initiative, it is working to grow its collection and its program to cover South and Southeast Asia, Latin America and Middle East and North Africa. However, can there be such a thing as a 'global art museum'?

RAYes. There can be. Can there be one that is accurate and adventuresome at the same time? That causes a lot of trouble.

We have approached it by using two different strategies. One strategy was to build physical outposts in different spots. We were given Venice by Peggy when she died because she wasn't able to give it to her children. She had been in negotiations with Tate and in the end she gave it to her Uncle's foundation—so that was more than 30 years ago. In fact at the incorporation of the Foundation you will see in the papers that in 1937 they were talking about the Museum as being in more than one site.

So there is a strategy that says 'yes I can be global and I will manifest that by being at various places around the world'. However, our definition of 'world' has so far been largely Europe and America. That is changing even today as we go to the Middle East. So there is one strategy.

What's another strategy? And this is the one we sort of collectively cooked up—why don't we have intelligence from the outer world come to us in the form of curators and ongoing dialogue where together we look at what's worth collecting and what's worth talking about. We can then consider how we respond to the questions posed by the people involved; and then what are the auxiliary activities that can make that dialogue intriguing.

So we made the BMW Guggenheim Lab go away from New York and be on the street in India and be on the street in Germany.

The Initiative was conceived right from the beginning as being a means of adding works to the New York collection, but also of sending those works back to the region they came from so that they can be looked at in a critical way by a different audience in the hope that the cross dialogue will be fruitful for both sides. And maybe for the first time ever rather than always privileging the curators we also asked the educators to be central to the exchange because they are the ones who really interpret everything and more frequently are engaged with the public.

So it can be done. It is vexing and it looks from the outside to be occasionally egomaniacal, but on the other hand if you have confidence in what we are collectively thinking about, why shouldn't we, as intellectuals, be willing to stand up and be able to say what we are doing is worthy of being considered inside the activity of humankind.

Well you discover how big the world is physically and that is a simple, but very meaningful discovery.

ADThis second strategy reflects a move by the Guggenheim to be more focused on being a catalyser of ideas and instigator of global art conversations?

RAWe often think about ourselves today as a convenor. So we say yes we will bring together interesting parties and yes we will foster their talking in depth while they are together; and through other media we will also allow them to have a conversation that goes on over time—sometimes catalytic and sometimes nothing happens, but we are always willing to be the convenor.

ADSo in relation to No Country: Contemporary Art for South and Southeast Asia—once the final iteration of the exhibition in Singapore closes its doors, then how do you see a continuation of the work that has been done up to that date?

RAI see friendships and alliances being made where people say: 'Oh by the way—he, she or they are people whose opinion I particularly value. I am not going to make a decision about this subject without incorporating information from he, she, it, they'.

And therefore as we invest our relatively limited money in exhibitions and acquisitions, I am not going to pick from the variety of what is available without having better knowledge of what is coming from that part of Asia. So I see it as a way of expanding horizons and also connecting people, and then asking them in a very point blank way: 'Are you really thinking of this globally?'

ADThe focus of the Initiative does seem to be about the expansion of knowledge. What have you personally learnt from this exercise?

RAWell you discover how big the world is physically and that is a simple, but very meaningful discovery. The other thing that I always have great hope in - because we live in a pampered and relatively overly refined environment in Manhattan—is to get reignited by recognising that the audience are inquisitive people and they are made from many ages and frequently from many economic classes predominantly what we might think of as 'lower classes'—so I find that particularly re-invigorating.

ADWho were the people who came to see the New York iteration of No Country?

RAWe got a very wide variety of people. Let's say that 60% of them would have been people from outside Manhattan and a lot of them would have been Europeans and Asians. Also in that particular exhibition we saw a lot of teenagers.

Today it has the big advantage of being somewhat friendly, but utterly memorable; and that is a new attribute.

ADWhy did it appeal to teenagers? Did schools drive that?

RANo, word-of-mouth. They were kids. Our demographic skews to the youngest of all the museums. Partly because the Museum is kind of interesting looking and it is activated so that the boys don't feel they are going to be trapped in there—'I can do something kinaesthetic. I can run. I can move quickly.'

I mean one way you can look at the Guggenheim—and this might answer your question—you might see it as the first museum that is not based on a palace. It is actually based on a parking garage.

It is based on Bauhaus parking garages from the 1920s which Frank Lloyd Wright had studied, without having seen, in an effort to make a museum outside Baltimore Washington that was for a car collection. He would never feature that aspect of what he was thinking about, but it had a very utilitarian origin and I think it took a long time for the Museum to be seen as utilitarian.

Today it has the big advantage of being somewhat friendly (depending on how mobile you are), but utterly memorable; and that is a new attribute. You and I live in these white boxes that can be in Mozambique, in Brazil or in Halifax, we don't really know where we are. So it is very, very helpful that at the Museum, and even in Venice, and certainly in Bilbao, and I hope in Abu Dhabi, people are inside a very particular space that they recall and therefore they also remember what they saw there.

ADThe New York Guggenheim's space directs you. Which is good, but it must be difficult to work with?

RAYes it is good, but it can be irritating, and expensive. The thing I sometimes don't like is that when I see a picture sometimes I would literally like to go behind it and I can't do that. And I can do that elsewhere. I like sometimes to see the picture, the story enfilade—moving back.

Instead I am forced to see it en passant. I am always forced to see it sideways. I have to be careful and make sure that I turn around and actually look at the painting—at the sculpture, or whatever it is.

I find that sometimes we are not serving our public well by making it too open-ended.

ADThe No Country exhibition at the Guggenheim was a much larger exhibition than the exhibition here at the Asia Society. Here there is a select group of works and it appears to be an exhibition very much focused on ideas that resonate within a region, rather than the region itself.

How do you view the changes in the exhibition from New York compared to the works as they are shown here in Hong Kong?

RAI don't want to criticise New York, but I think in some ways, this is a richer and more difficult exhibition here. Things are said editorially in the galleries, that we would never have had the courage to say in New York. It allows me to see what I am looking at in a different way that is better and more synthetic.

If you read what is put on the walls in the Hong Kong exhibition—it is tough. They have made some very strong assertions. They are quite interesting.

It allowed me to look at what I am seeing through a certain lens and therefore I felt I got something from it.

I have just come from the Biennale in Singapore. The Biennale organisers took the approach of appointing 27 curators with distinct knowledge of different areas of Southeast Asia art practices.

ADAlthough recognising that Biennales are very different beasts — how do you view this approach of appointing a number of curators versus the approach of MAP Global, where only one curator has been chosen?

RAMy cynical experience is that a great number of curators are going to be a problem. But it may be that in the newly democratised world that is going to be more typical.

We thought, and I still believe, that it is useful when we are starting from a very elementary point to have a single point of view uniting what it is that comes into the Collection.

I find that sometimes we are not serving our public well by making it too open-ended. I think sometimes it is better, even though you may not come up with the ultimate and best solution, frequently in our world to say: 'this is the best we can do, it's finite. It is one person's point of view and we endorse that view while recognising that it may be faulty. —[O]

No Country: Contemporary Art for South and Southeast Asia, Asia Society Hong Kong Center, 30 October–16 February 2014