Sabih Ahmed: Expanding the Definitions of South Asia

Sabih Ahmed. Photo: Jalal Abuthina.

Sabih Ahmed. Photo: Jalal Abuthina.

Sabih Ahmed is a curator steeped in interdisciplinary thought, whose multi-faceted practice bridges languages and technology, geographies and movements, archives and art history.

Ahmed joined Ishara Art Foundation as associate director and curator in February 2020. Founded by the Dubai-based patron and collector Smita Prabhakar, the non-profit fills an important gap when considering there are currently no institutions dedicated to South Asian contemporary art outside the subcontinent, not to mention the politics of representation in the GCC, a place of intersecting histories and diverse communities.

Recent exhibitions that Ahmed has organised at Ishara include Growing Like A Tree (20 January–1 August 2021), the first chapter in a two-part show highlighting trans-regional connections and emerging artistic practices across Bangladesh, Cambodia, Germany, India, Myanmar, Nepal, Pakistan, and Singapore.

A collaborative project with artist Sohrab Hura, Growing Like A Tree engaged an expanded field of photographic practice through videos, books, and sound installations by 14 artists and collectives—including Aishwarya Arumbakkam, Nepal Picture Library, and Yu Yu Myint Than—and dealt with themes of sociopolitical change, urban myths, and collective memory.

The follow-up exhibition, Growing Like A Tree: Static In The Air (11 September–9 December 2021), comments on exhibition-making as a fluid form that gradually unfolds in layers by transforming the first show both visually and aurally.

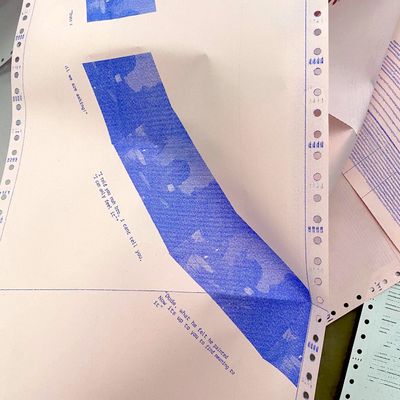

New works sit with works from the first iteration, several shifting in scale and volume. Reetu Sattar's Lost Tune (2016–2018) is amplified in sound, Farah Mulla's work Aural Mirror (2013) goes silent, while Rahee Punyashloka's film Noise reduction II: Chinatown (2014), a mediated landscape of material corrosions, spliced imagery, and fragmented voiceovers is introduced alongside a new installation by The Packet collective that creates the soundscape of a dot-matrix printer emitting reams of paper into the exhibition space.

While Ahmed's curatorial work focuses on modern and contemporary art of South Asia, a conversation with him often lends itself to wide-ranging references from media theory to Continental philosophy. He is actively involved in education, having served as a visiting faculty at the Ambedkar University Delhi from 2014 to 2019 teaching Art & Technology and Curatorial Investigations.

Ahmed's independent curatorial projects include The Superhero Sighting Society (2019) exhibition and symposium in collaboration with artist Taus Makhacheva at KADIST and Centre Pompidou in Paris; and he was among the ensemble of curatorial mentors for Five Million Incidents (2019–2020), a year-long event series organised by Goethe-Institut, Delhi & Kolkata, and conceived by Raqs Media Collective.

Ahmed began his path as a researcher at Asia Art Archive (AAA) from 2009 to 2019, where he played an instrumental role in establishing AAA in India. He is currently working on three dossiers entitled Writing Art with Sneha Ragavan, Vidya Shivadas, and Santhosh S., which delves into how modern art movements were formed through texts by artists, critics, and historians in English translation.

The Writing Art series follows an AAA bibliographic project comprising a database of 20th-century art writing from India in 13 different languages: an example of Ahmed's sustained engagement with Asian art histories, which he discusses in this conversation in relation to his work with Ishara Art Foundation and beyond.

NKYour curatorial approach is quite collaborative, as exemplified by your recent project with artist Sohrab Hura. How did the idea for these two exhibitions at Ishara come about, and how did you engage with Hura in particular to curate them?

SAI have long admired Sohrab as a photographer and filmmaker, not only because of his works but also because of how he situates himself within a network of practitioners who support one another in precarious conditions.

While I was aware that Sohrab had not curated an exhibition before, I wanted to invite him as an opportunity for both of us to think together about how fields are created and nourished based on solidarities. This felt timely, especially with the onset of the pandemic.

Our conversations began with three conceptual provocations that I sent him. The first was: how can an exhibition measure the velocities and circuits through which images move in the contemporary moment?

The second: how can an exhibition enact geographic realignments that are not based on political maps but rather on collective journeys? And the third, inspired by Hito Steyerl's In Defense of The Poor Image (2009), how would Sohrab present his 'visual bonds' today, based on affinities with practitioners who are also invested in certain kinds of image-making?

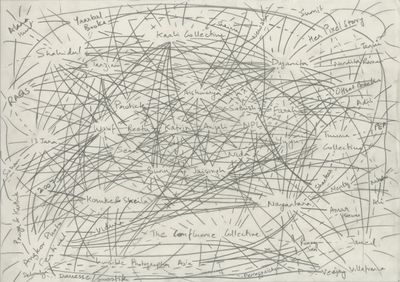

Sohrab responded after a few weeks with a concept that was in the form of a drawing, a Map of Interconnectedness, which became the blueprint of the exhibition. The first iteration titled Growing Like A Tree captured the fragile yet resilient networks in which various practitioners operate.

I believe curation is a practice that tests political and aesthetic possibilities of assembling, be it an assembling of objects, ideas, meanings, events, or people.

While we had only conceived of a single iteration, it became apparent that this tree must grow into a forest. This led to the second iteration titled Growing Like A Tree: Static In The Air. For Ishara, the exhibition opened a whole new way to think about South Asia through contemporary art.

NKCould you talk about the content and form of these two exhibitions? What was the process like in terms of devising a theme and thinking about what artists and artworks to show?

SAFrom the outset, Growing Like A Tree was less preoccupied with themes and more with methodology. During the 11th Shanghai Biennale, Why Not Ask Again: Arguments, Counter-arguments, and Stories (12 November 2016–12 March 2017) curated by Raqs Media Collective, where I was one of the four Curatorial Collegiate members and Sohrab was one of the participating artists, we reflected on Raqs' proposition to consider curation as a way of drawing itineraries rather than inventories, and producing milieus rather than themes.

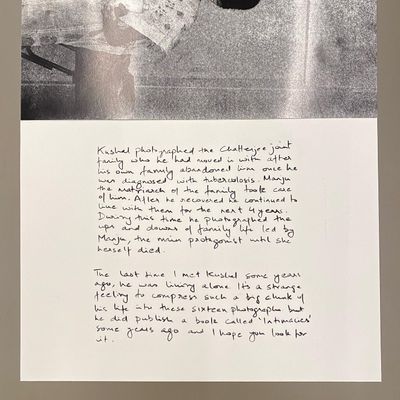

This pushed us to think about the exhibition at Ishara as a site where artistic paths could intersect, where artworks could form entangled clusters, and the architecture of the gallery could be rendered like pages in a journal. Conveying the collective journeys that Sohrab finds himself amidst, the artists in the show are not limited to those whose artworks are installed.

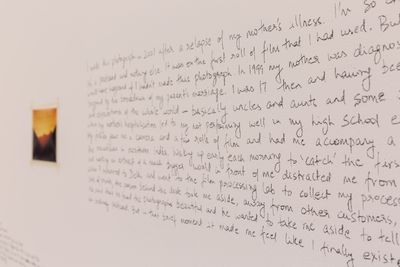

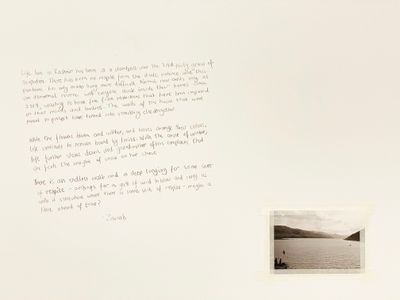

On the contrary, the exhibition layers artworks alongside image notations, handwritten notes on walls, and artistic citations of various others who expand the framework of the content and the artists present.

With the second iteration, this framework expands even further as Sohrab has choreographed a series of transformations during the opening week (11–16 September 2021) where select artworks and notations from the first one continue into the next, new clusters emerge while others fade out. One can sense from Sohrab's curatorial approach the shift in image-making discourse today.

For one, you realise there is not a single still image in the show. On the contrary, they are in constant flux. The exhibition embodies this flux that seems emblematic of the contemporary.

NKWhat artworks of note have been included, how are they presented curatorially, and how do the two iterations connect?

SAStatic In The Air refers to a tuning of sonic frequencies. Just as when one switches radio stations encountering bursts of noise, interruptions, and static, the second iteration tunes into more artist voices to create new intensities.

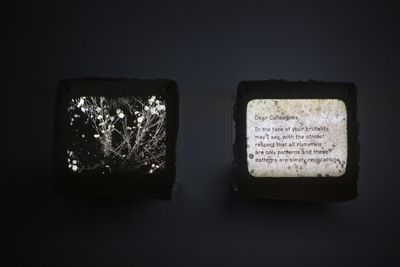

One such cluster resonating from the first iteration was formed around a work by Farah Mulla titled Aural Mirror, a sound installation with three microphones and two speakers that exerts a pull towards the corner where it is placed.

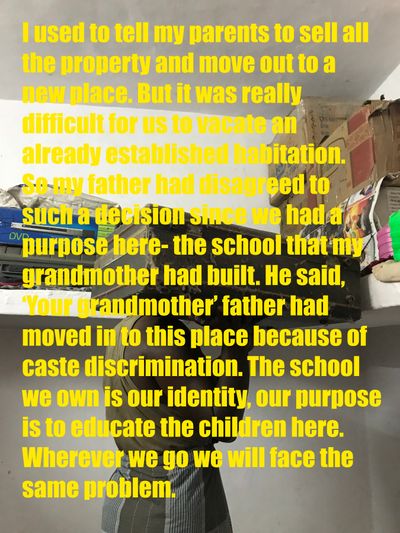

Surrounding it was Sathish Kumar's 'Town Boy' series (2011–2020) and Jaisingh Nageswaran's I Feel Like A Fish (2020), both of which reference autobiographic narratives emerging from places in which they grew up. Together, the pieces are coloured differently with Farah's sounds, which also originate from a personal narrative.

...internationalism always takes on different forms in different locations. It is about how the world is configured around you based on where you are...

In the second iteration, Jaisingh's work, comprising textual anecdotes superimposed onto images, becomes a notation orbiting Zainab's photographic series 'The Weight of Snow on her Chest' (2019–ongoing), made during the pandemic in Kashmir. Adjacent to it is another photograph by Jaisingh that was previously small and now enlarged.

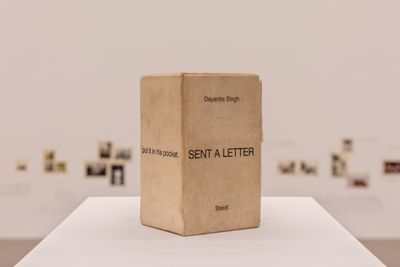

This switch has changed the tonality of the entire exhibition as it is staged near Farah's now-silent sound piece. Another work I would like to mention is Dayanita Singh's Sent A Letter (2007), a set of seven photobooks encased in a box with a text running around it.

Typically, this work is presented open and unfolded to render the book as an exhibition. For Growing Like A Tree, the work is seen enclosed as an object to be read. Sohrab placed his personal copy of Dayanita's work as a citation in the show, paying tribute to someone who has inspired and supported not just his own work when he was starting out as a photographer but several others in this exhibition.

NKSince this was Hura's first curatorial venture, what was it like as a curator providing the platform for an artist to curate?

SAI am quite resistant to the idea of seeing my curatorial role as someone who provides a platform or space to others. That sounds more like a real estate agent or developer. As a curator, I see myself as an interlocutor with artists, other curators, and colleagues.

The invitation to Sohrab was towards thinking together about what new ways we could explore the fields we inhabit, different readings of works that can emerge when presented at Ishara, and other directions that might open in our practices when we work together. This creates pathways where we as an institution also learn.

NKYou've been thinking about the public(s) in relation to institution-building as a volatile space. How do you see curatorial practice evolving with different publics at a time when institutions are redefining themselves structurally and conceptually because of a global pandemic?

SAI think of the relationship between institutions and publics as volatile, because the public is not a given entity. Each period and each context produce different forms of publics, which are spaces of struggle and negotiation.

The idea of the public today emerges out of recent histories of the Arab Spring, BLM, #metoo, the ongoing pandemic, not to mention countless other movements. This is a public that is connected, informed, and engaged. It participates rather than consumes. We can see these shifts in art practice as artists are part of these movements.

Curatorial practice therefore faces an exciting challenge of testing new templates and interfaces for encountering art conceptually, performatively, and corporeally. This places a different pressure onto institutions where existing formats for exhibitions, programmes, pedagogy, and public outreach are also more participatory and self-reflexive.

I find that the advantage with independent art foundations is that they can be relatively more agile in adapting and testing ideas amidst uncertainties such as the pandemic.

NKHow effectively can curatorial practice become a laboratory to probe new ideas about the world at a time of ecological and geopolitical unpredictability? How do you even measure impact when footfall is no longer a real signifier?

SAI believe curation is a practice that tests political and aesthetic possibilities of assembling, be it an assembling of objects, ideas, meanings, events, or people. The impact of this practice cannot be reduced to quantifying footfall, which might be important for selling tickets where it's necessary.

If exhibitions are like telescopic observatories through which you apprehend vast distances, at Ishara, we try in our modest way to see what the world looks like from different vantage points...

The impact of artistic and curatorial work in my view is measured by how it contributes to new ways of thinking about history and the present. If it is to be measured in concrete terms, I would base it on how it is disseminated through discourse, educational curricula, publications, citations, and so on, all of which take time.

NKDuring your time at Ishara, you've worked on a solo by an established artist, Amar Kanwar (Such a Morning, 20 January–30 May 2020), a collection-based show (Every Soiled Page, 19 September–19 December 2020), and experimental curations such as those with Sohrab Hura. Is this the direction you see developing in the future in terms of showcasing different types of exhibitions?

SAYes, we intend to have a cycle of exhibitions that include established practices by artists who have been working for several years; experimental curatorial projects that test new methodologies of exhibition-making; and collection-based shows that bring together constellations of practices from the collection of Ishara's founder and chairperson, Smita Prabhakar.

The exhibitions we aspire to organise are with practitioners who have not been presented in any substantial way in the Gulf, since we are interested to see what these crossovers instigate here.

NKWhat role does Smita Prabhakar's collection play in all this?

SASmita has been collecting contemporary art from India for over 20 years. Until recently, it had remained primarily a private endeavour of hers. Since the founding of Ishara in 2019 as a space dedicated to contemporary art from South Asia and South Asian diaspora, there was an awareness on her part that the collection goes beyond a personal interest.

It is also a means of supporting certain practices in depth and finding avenues where they can be shared with the world. From this year, the collection is referred to as 'The Ishara Art Foundation and Prabhakar Collection', because of the synergy between the foundation and the collection.

With this shift, the collection has widened in scope to include works of artists from South Asia and its diaspora, as well as lend works to other institutions globally.

NKWhat is in the collection? What themes and trajectories does it follow?

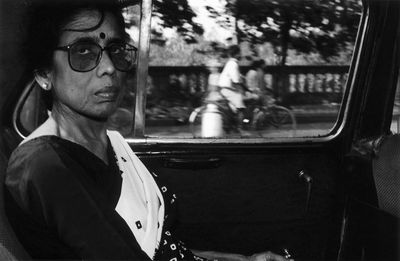

SAZarina, Lala Rukh, Simryn Gill, Dayanita Singh, Jitish Kallat, and Shilpa Gupta are some of the artists whose works form an important part of Smita's journey as a collector.

As it might already be apparent, the collection has a strong presence of women who have contributed to contemporary art in the past three decades, and it leans towards contemporary photography and conceptually driven works, two trajectories that deserve more recognition than they receive in the region.

NKHow do you position Ishara between being international in scope and yet culturally anchored in the specific context of the U.A.E., itself a site of trade and transit?

SAContemporary art from South Asia is international in scope anyways. Having said that, internationalism always takes on different forms in different locations. It is about how the world is configured around you based on where you are—which places seem close and which ones seem far; with whom do you start identifying your history and whose histories become distant. In the U.A.E., these questions seem to get heightened because of the vast movement of people.

If exhibitions are like telescopic observatories through which you apprehend vast distances, at Ishara we try in our modest way to see what the world looks like from different vantage points and what art from South Asia offers when presented in the U.A.E.

NKWe've often spoken about expanding definitions of South Asia. Why do you think it's so important to interrogate and complicate regionalisms today?

SAIt is important to tell different stories and to tell them differently. The most dominant stories of the 20th century, passed down all the way from academic curricula to movies to museums, are exclusionary, racist, sexist, and war-driven.

The impact of artistic and curatorial work in my view is measured by how it contributes to new ways of thinking about history and the present.

They were based on essentialising ethnicities, gender, cultures, and regional identities. In effect, they have perpetuated what is universal and what is regional. We live in a world that is far too complex.

What can be more stirring than complicating these essentialisms to invent new vocabularies and ways of thinking about what Donna Haraway describes 'worlding'? The interest in expanding definitions of South Asia is anchored in the recognition of these complexities and a commitment to finding new possibilities with others.

NKHow do you feel about the state of regional survey exhibitions on South Asia?

SAThere was a moment in the early 2000s when survey exhibitions on South Asia were widely prevalent. On closer look, you'll find how much they pivoted around India. In hindsight, it is hard to miss how much they corresponded to India gaining prominence in the global economy.

To me, those exhibitions signify a moment in the era of globalisation, where certain nation states and regions were being marked for their foothold in booming art markets—first Japan, then China, then India. We see a lot less of that now.

I did often wonder at that time what a survey exhibition of Europe or North America would look like. Who would curate it, and how would countries and cultures be represented through their artists?

A survey exhibition that did seem distinct was Century City: Art and Culture in the Modern Metropolis, curated by Okwui Enwezor at Tate Modern in 2001. The exhibition looked back at the 20th century through the lens of important cultural centres that were not the traditional ones (Paris, New York, Vienna, Moscow and London), but rather, Mumbai, Lagos, Rio de Janeiro, and Tokyo.

Enwezor invited other curators into the fold such as Geeta Kapur, Ashish Rajadhyaksha, and Olu Oguibe. This felt like an important move that explored the survey form through multiple de-centred nodes.

NKOkwui Enwezor's 'Platforms' in different cities were a huge influence on you in terms of the way he conceptualised these sites as nomadic yet rooted reflections of the contemporary—a model embodied at AAA. What is your guiding principle at Ishara?

SAEnwezor conceived the Platforms as 'rehearsals for the repositioning of sites of discourse production'. In a note by Raqs Media Collective written after his passing, they narrate that when they met him a few months prior, he had returned to the idea of Platforms claiming that it has to do much more now: '(it) has to be nomadic, dispersed, searching, and yet have a stable location so that it can gather and appoint dispersals.... It has to be hospitable to the untested and uncharted present.'1

I feel that organisations such as Asia Art Archive, Ashkal Alwan, and Sarai in some sense embodied what Okwui had articulated in the early 2000s. I can only aspire that at Ishara we can chart some of these possibilities attuned to the ongoing global shifts in the art world and beyond.

NKHow does your process engage with the idea of the centre and the periphery?

SAI find the idea of centre and periphery difficult to relate to. In his book Traité du Tout-Monde (1997), Edouard Glissant argues that the whole world is becoming an archipelago.

His notion of 'archipelagic thinking' inspires me much more. He proposes that regions can be best understood through cross-cultural examination that focuses less on isolated territories and more on how the places exist in relation to one another.

NKYou began your studies in art history and cultural studies, which obviously impacted your curatorial practice.

SAI pursued my higher education in art history at the Fine Arts Faculty in the Maharaja Sayajirao University in Baroda, and then in an interdisciplinary cultural studies programme at the School of Arts and Aesthetics in Jawaharlal Nehru University in Delhi.

I find that the advantage with independent art foundations is that they can be relatively more agile in adapting and testing ideas amidst uncertainties such as the pandemic.

I was fortunate to have been in an environment where there was a wide exposure to critical thinking and political urgencies. Therefore, my learning about art was always anchored in gender studies, post-colonial, and philosophical investigations.

This produced an awareness that the dominant canons in museums and books needs to be questioned and rethought. During my student years, I also encountered independent research spaces such as Sarai in Delhi.

These were spaces that pushed you to develop new methodologies and find peers with whom to develop alternative ways of thinking about cities, society, technology, and art. All these factors opened pathways that I feel continue to be relevant for me today.

NKHow was the transition to Ishara Art Foundation after ten years at Asia Art Archive?

SAAt AAA, I had the experience of working closely with artists, thinkers, writers, and developing research and curatorial projects. Even though a lot of my work there focused on India, at a broader level we were working towards positioning modern and contemporary art in Asia through a prism of complex geographies. My transition to Ishara expands the radius of those explorations.

NKAt AAA you developed frameworks that offer new critical perspectives into South Asia's place in global art history. How does Ishara locate this research and curatorial practice?

SAThere is still so much to unpack in the histories and contemporary realities of Asia. At Ishara, I'm interested in initiating projects that look at entanglements, which include diasporic narratives, the relationship between South Asia and the Gulf, and multidisciplinary collaborations across fields.

NKWhat kind of archives do cultural institutions leave behind and how accessible are they?

SAI believe that cultural institutions leave their imprint in at least two ways. The first is a concentration of archival materials they have produced, collected, and preserved, which becomes a valuable resource for future research.

But there is another, more dispersed kind of imprint, which finds its way into the practices of artists, curators, and thinkers with whom the institution has worked. It reveals itself through the oral histories of practitioners, and through concepts, vocabularies, and new methodologies that a collaboration with an institution might have seeded, and takes on a life of its own.

This is something I am always aware of in my role at Ishara. For example, what are the intellectual and artistic contributions that an institution can make in contemporary practices?

NKWhat can we expect to see from Ishara in the near future?

SAWe are planning to set up The Reading Space in 2022, inviting different practices of reading. Besides operating like a library with a collection of books for visitors to read, we will invite practitioners from different disciplines to come and share how reading is done in their respective fields.

It will be a space for programmes and site-specific interventions that unravel the tools and techniques required for the reading of galaxies, minerals, and cities, for instance. We are also looking forward to continuing our association with some of the university programmes in the U.A.E. that we have had the chance to work on since 2020.

We are also planning solo exhibitions for Jitish Kallat and Navjot Altaf in 2022. Our partnership with Colomboscope in Sri Lanka is something we look forward to continuing, which will culminate into an on-site Reading Room project in Colombo next year.—[O]

1 Raqs Media Collective, 'Remembering Okwui Enwezor', e-flux Journal, Issue 98, February 2019. Link: https://www.e-flux.com/journal/98/260819/remembering-okwui-enwezor/