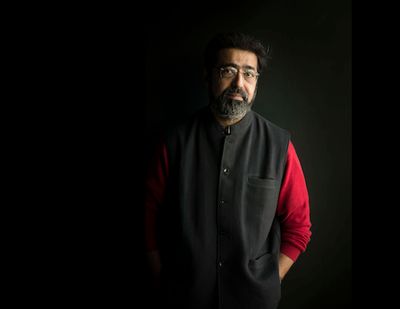

Amar Kanwar

Artist and filmmaker Amar Kanwar is known for work that expands on the idea of the video essay, the documentary, and the archival practice. His 2013 exhibition at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park, The Sovereign Forest + Other Stories, was a case in point.

Part of an ongoing installation, The Sovereign Forest, which continues to expand and grow, is comprised of videos, books, sculptures, photographs, and an archival installation.

Each work on show portrays the exhaustive resistance movements that have responded to abuses of power in India, particularly in the region of Odisha.

In this interview, Kanwar talks about the project as a space that continues to transform.

SBHow did the iteration of The Sovereign Forest at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park differ from previous times you have shown it, from dOCUMENTA(13) and Sharjah Biennial 11 to the Kochi-Muziris Biennale?

AKTwo types of changes take place in the installation whenever the project moves. One is when the project moves from one location to another. The other is when it changes from within itself, in the way it is installed; things are added and changed, rather than removed, so there is a totally different feeling. Between dOCUMENTA 13, Sharjah, and Yorkshire, the results have been varied. Of course, this is obvious in how the installation is presented. It depends on the space you end up with. In Sharjah, it was on the fifth floor of a former bank building, and in Kochi, it was in a barn that had not been used for some 40 to 50 years, so there was rubble and no roof. In fact, Kochi was the first time we conceived of The Sovereign Forest in much 'longer form', so to speak, whereas at dOCUMENTA 13, it was more contained in one space.

SBAnd how did it change the Yorkshire Sculpture Park?

AKThe installation at Yorkshire Sculpture Park was one of the most interesting, from a design point of view. One aspect was that we were able to create a countered space within the whole installation. From the point of view of the viewer, we were also able to create movement, in that one could move from one form of language into another form, say from a video, The Scene of Crime, to the installation of books in the central room, where the design activated the peripheries of the space. So we did get a central space that was charged with a certain energy. Yorkshire was also the first time I was able to bring in the evidence accumulated over one year in the permanent installation of The Sovereign Forest in Odisha.

SBYou mean the permanent installation of The Sovereign Forest, which opened on 15 August 2012 at the Samadrusti campus in Bhubaneswar, and which continues to collect material related to the struggles in Odisha?

AKYes. Everything that was there in that room was first installed in August 2012, and then re-installed on 15 August 2013, when we made a big second opening for the space in which we integrated all of the material we had collected over the year. I would say it was the first time the local public, who had been coming to the space repeatedly, were able to actually see the space transformed from one kind of installation, or space, into another kind of space. So, Yorkshire was also the first time I managed to provide a really good glimpse into things collected over the year in this evolving work in progress: the installation in Odisha.

Then there were other things I was really happy about, and in some way I think am listing them here in order of importance to me, from the design to the opportunity to present the evidence. I felt that there was probably no better place than the Yorkshire Sculpture Park to push what was inside_The Sovereign Forest_ into the outdoors, through the sculptures and The Listening Benches, which I created from the 19th-century wooden organ pipes from a church on the YSP estate. The benches also gave an idea of the multiple tree species available in Yorkshire.

SBThe Listening Benches were placed in parts around the Underground Gallery. These were hollow, and within them were recordings of you narrating various stories, including one about The Counting Sisters, characters who form the title of one of the books presented in the central space. Then you have the sculptures themselves: seven upright wooden pipes that represent the sisters as The Six Mourners and The One Alone.

AKThe sculptures are connected to the book in the show, The Counting Sisters, and as a book, it supposedly ends in that the book has a start and a finish and specific chapters. But The Listening Benches continue these stories. They aren't written but transmitted orally and are only accessible as such. So the stories leave the printed, text form and get out into the open orally. The organ pipes that are installed in the garden are inscribed with text from the film, The Scene of Crime, so the text in the film actually leaves the image and gets out into the open, too.

SBAnd these newer, site-specific works are somehow related to the mining history in Yorkshire itself, is that right?

AKWell, the first time Clare Lilley and myself met many years ago, and she brought up the possibility of doing this exhibition. She referred to the history of the park and as I learned more, I learned that YSP worked with the surrounding communities and have a relationship with the land and the people who live on it. I know the issue with the miners was another struggle and it happened at a different point in time, but I think in a certain way, the people here know the land and they understand people working on the land, whether it is miners or farmers.

SBAnd they have this experience of loss, too, as do the communities you have worked with in Odisha.

AKYes, precisely. But personally, for a couple of years, perhaps a little more, I worked as a researcher in coal mining areas in central India, so I have been researching mining in India for quite some time.

SBThis also links to the work you did in and on Chhattisgarh, documented in the book you created,The Prediction (1991—2012), which charts similar local struggles that took place in another region-rich area of India, right next door to Odisha, including the assassination of the civil movement's leader against corporate encroachment on Chhattisgarh's lands, Shankar Guha Niyogi. So, when exactly did you start working in Odisha?

AKBy 1999 I was filming in Odisha, but I think I started to go there with the intention to film maybe in 1997 or 1998 . . . then I really started working there in 1999.

SBAnd one of the new books in the main space, Time (2013) is like The Prediction in many ways, in that it is a really extensive log of the fight between the local population, and wider state and international interests in the region itself.

AKFor me that book is quite important. For anybody who has been engaged with small or large community movements or political organisations and political campaigns, especially if they are rurally based, with large, varied kinds of people involved, comprehending what is happening has always been a problem. This is because so much happens, and every story you tell is inadequate, in a way, because there are many problems happening in Odisha internally, too, as well as other things happening around that. So it is difficult to get an idea into how much time goes into fighting to keep your own space, or dignity, or to document how much gets lost. So the book gives a sense of what goes in to such struggles. It is still going on, this resistance. The book is not a log, but more like research documented by people that I have worked with, containing information and facts that produce a timeline of the resistance. But then you have this issue that every timeline has a second timeline.

SBIn that it doesn't have a beginning and an end? But when did the timeline start for the book?

AKIt starts with the signing of the Memorandum of Understanding that was signed between the Indian Government and the South Korean steel company, POSCO. I printed it at the end of July in 2013, so that is how long the movement has held off POSCO. It gives you almost a week-by-week or blow-by-blow account of the entire game that is being played out between POSCO, the state, and the resistance, so it gives you an idea of what it really means to resist as a community. —[O]