Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale: The World's Largest Outdoor Art Festival

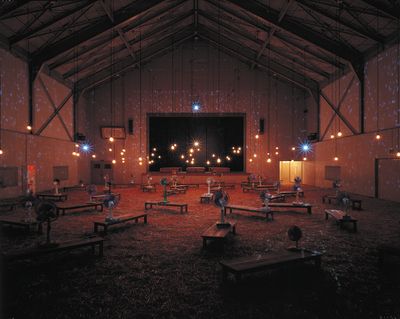

Akiko Utsumi, For Lots of Lost Windows (2006). Courtesy Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale. Photo: H. Kuratani.

Running since 2000, Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale, the largest outdoor art festival in the world, injects art into the landscape of Japan's snow country, littered in the summertime with phosphorescent, green rice paddies that lie flat beneath the mountains of the southern part of Niigata prefecture. Rather than assigning each edition with a new curatorial concept or title, the Triennale follows one overarching premise: 'humans are part of nature.'1 As such, considerable attention is paid to the landscape and those who call it home. Between editions, the Triennale runs programmes led by the NPO Echigo-Tsumari Satoyama Co-operative Organisation, which fosters networks between the local population and those involved in the exhibition.

This year, the Triennale runs for 51 days between 29 July and 17 September 2018, and includes 378 works, including musical and dance performances, spread across a 760 kilometre2 site. Locations include, among many others, the former Kamigo Junior High School, an abandoned doctor's clinic, and approximately ten traditional wooden houses spread out across the territory, which have been left vacant for reasons that include an ageing population and the 2004 Chūetsu Earthquake.

The centre point for the Triennale is the Hiroshi Hara-designed Satoyama Museum of Contemporary Art, an exposed concrete complex centred around a shallow, square-shaped pond located in the city of Tōkamachi. Overlooking this pond are the immense windows that encase the main exhibition space, which consists of a walkway that runs along the four sides of the museum, throughout which a discordant yet playful number of 12 installations are installed. Carsten Höller's Rolling Cylinder (2012) is a dizzying, cylindrical installation whose sides spin around the viewer as they walk through its red, blue, and white swirling interior; Leandro Erlich's Tunnel (2012) warps viewers' perspectives as they walk through its darkened interior towards a trompe l'oeil that appears as an exit onto a mountain road—a visual reference to the tunnels that slice through the local landscape.

Outside, the pond's concrete banks provide space for a series of architectural prototypes, including Jiro Ogawa/Atelier Simsa's soba noodle stand constructed from disposable chopsticks and Thai architecture firm all(zone)'s LIGHT HOUSE 4.0: The Art of Living Lightly: a light, transportable structure intended for a young urban generation living in tropical regions that do not have access to proper housing. Replete with stands selling coffee and shaved ice on the opening day, the museum's outdoor area felt like a summer fete as children darted about the installations and cooled their feet in the pond at the mercy of another of 2018's heatwaves.

For their project Twenty-Five Minutes Older, Hong Kong artists Kinglsey Ng and Stephanie Cheung invited visitors to board a camera obscura bus, which juxtaposed imagery of the landscape that flooded the interior through two apertures, with short excerpts of text projected onto one of the walls. The excerpts were abstracted from conversations that the artists held with seven local residents. These include an encounter with a punk musician from Tokyo who relocated to the area to learn to live with nature, and an elderly gentleman in his nineties who has witnessed many drastic changes in the area over the years. Besides the functionality of the bus as a means of moving between artworks, the project also enables viewers to reflect on a range of topical issues particular to the area—from changing demographics to the consequences of rapid modernisation.

Personal engagement was also present in the newly erected Hong Kong House, a 'cross-region art and cultural platform' designed by a team of architects led by Yip Chun-hang, which represents one of a number of external collaborations. For the space's inaugural exhibition, Tsunan Museum of the Lost (29 July–17 September 2018), artists Leung Chi Wo and Sara Wong met with local residents and amassed over 50 photographs taken between the 1960s and 1970s, which they then carefully arranged in glass-topped tables. Each snapshot is brought alive by an anecdote written alongside it, while seven large-scale photographs on the opposite walls capture Sara Wong and Leung Chi Wo acting out the personalities of unknown individuals present in the photographs. Against a bright, white background, the artists stand with their backs towards us so that all we are left with to deduce each character is the clothing and movement chosen by the artists. In one image, a figure in a bright orange tracksuit stands armed with a badminton racket while in another, Wong has dressed in a deep blue winter jacket and stockings and stands expectantly with her hips on her sides.

Memory is a pertinent theme across this exhibition. Sound, sight and smell come together in Christian Boltanski and Jean Kalman's, The Last Class (2006/2018) to compound past and present in a monumental installation that is spread across the entirety of the former Higashikawa Primary School. On the ground floor, a heady smell fills the air as viewers walk into a darkened assembly hall, dimly lit by single bulbs that hang from the ceiling. The space is silent apart from the footsteps of other visitors who move softly across a thick blanket of hay interspersed with benches that are each bestowed with a gently humming fan. A sense of silence and comfort collides with underlying alarm, as wind and the hay's dryness combine to suggest the potential for a blaze.

Guided up the staircase by another series of dimly lit lamps, a thundering sound edged by the rattle of corrugated iron sucks viewers into a completely blackened room. Shuffling apprehensively and engulfed by a deafening thump, an intermittent lightbulb briefly illuminates the room—allowing viewers to catch a glimpse of each other in the room, as well as taps, tables and cupboards painted black.

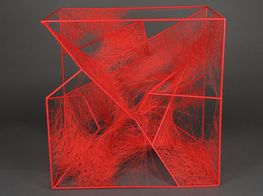

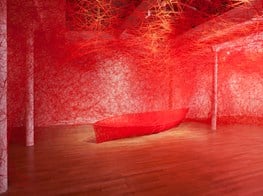

Darkness consumes many of the installations across the Triennale. This could be due to a reliance—or emphasis—on natural light. Works presented in a series of wooden houses include Chiharu Shiota's House Memory (2009), a vacant house filled with a web of black yarn; and Annette Messager's Les spectres de la maison Tsunné (2015), which fills an abandoned house with hanging stuffed toys shaped like scissors, nails and knives. While natural light brings these installations to life during each day of the exhibition's run, throughout the rest of the year, they will remain in situ, residing secretly in their assigned homes. (All the works in these houses will be maintained after the Triennale has closed.)

In the case of Shinji Ohmaki's installation Where the spiritual shadow descends (2015), a lack of light creates a purposefully exaggerated play on contrast. Located in an old house in Yomogihira village, viewers are engulfed in darkness as they ascend a narrow, very steep staircase to reach a balcony that overlooks a completely empty space. The silence is only interrupted occasionally when a smoke-filled bubble bursts as it ascends towards the ceiling.

The slow incorporation of the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale within the local context provides a refreshing contrast to the stop-and-go format of many large-scale exhibitions today, with an emphasis on slowness and subtlety—two characteristics that were emphasised in a parallel, yet independent exhibition at Yamakiwa Gallery, tucked away in a hamlet on the outskirts of Tokamachi. Yamakiwa Gallery inhabits a traditional wooden farmhouse lined with tatami mats centred around a deep pit filled with the ash of winters-past. The group show By Indirections Find Directions Out (1 August–2 September 2018), considers time's passage through the context of the gallery as a place where people come and go, as curated by Paula Lopez Zambrano. On the opening day, Mary Hurrell performed slow and methodic movements across a paper-covered floor, her footsteps marked by a pair of charcoal sandals that gradually gave way under her feat. A warping soundscape accompanied the action, created with field recordings of cicadas and other outdoor sounds.

Artworks by eight artists—including Carlos Santos, Dominic Hawgood, and Gaia Fugazza—were arranged over three floors. Love Enqvist's The Language of Flowers (2018) featured a transparent bowl filled with water and a small bunch of orange flowers, leaves, and branches, which was placed underneath a stream of light, like a still life waiting to be painted. On the opposite side of the room, Julia Varela's Mehr Fantasie (2018) presents a mass of silver dust on a short bench—the remnants of obliterated iPhones.

The crowd that attended this gallery's opening day consisted mostly of elderly village residents who were curious to inspect the artworks on view and ask questions about them. Over cups of cold sour plum brew, each person developed their own interpretations in a manner untainted by the pretense of 'knowing'—a freedom granted across Echigo-Tsumari by the Triennale's unusual avoidance of a curatorial theme. Instead of demanding to be seen, the artworks presented across the prefecture invite viewers to quietly contemplate what they could mean, while calling attention to the environment that they inhabit—a humble acknowledgement of nature as the greatest masterpiece of all. —[O]

—