French artist Christian Boltanski was known for his sprawling installations dealing with time, memory, separation, death, and the traumatic impact of the Holocaust.

Read MoreIn addition to thinking of artworks as an invitation for sustained contemplation about the past, Boltanski also believed they had a moral purpose to speak about universal problems. Christian Boltanski's art connected to the intense grief of mass atrocities, civilian deaths, and military conflict—facilitating, it seems, a necessary community catharsis.

Boltanski was born in Paris in 1944. His family was affected greatly by the Second World War. His Ukrainian Jewish father spent the entire German occupation hiding under the floorboards of his house, pretending he was divorced and separated from his French wife.

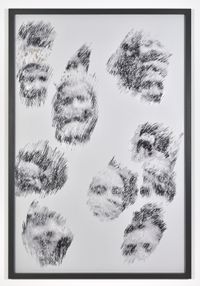

Influenced by museology and anthropology, Boltanski began by making sculpture, paintings, books, films, and photographs. He was especially interested in signifiers of the absent and forgotten.

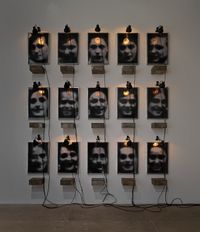

Boltanski collected and recontextualised found images and objects (such as old biscuit tins, articles of discarded clothing, photographs, bells, postcards, or documents) into installations such as the carefully arranged Monument (1984), with 26 photographs of a crumpled red stained cloth, three photos of pale anthracite, and, at the top, one solitary portrait—all illuminated by five light bulbs. Another example is the 1986 installation Leçons de ténèbrés in the Salpêtrière Chapel, Paris, with its lined-up found photographs and lights.

This pattern continued into the following decade with evocatively titled works like Réliquaire (1990), with its stacked tins, found photos, and illuminating lights, or Réserve: Les Suisses Mortes (1991), again with found photographs, and stacked biscuit tins.

In his later years, the artist began presenting more unpredictable projects, such as recording human heartbeats for a worldwide archive at Benesse Art Site, Naoshima (2005), and recording letters sent home by WWI soldiers to be listened to on four benches in The Leas, Folkestone, facing the English Channel (2008). Another death-related work Boltanski constructed was After (2017–2018), a huge installation designed for a church and cemetery in Amsterdam, where visitors were recorded in a confessional chair whispering the names of the dead, contributing to a pool of documented sound that can be replayed after the artist's or visitor's death.

One evening in 2009 after a drunken dinner, the inveterate gambler (and millionaire founder of the Museum of Old and New Art (MONA) in Tasmania) David Walsh proposed a wager to Boltanski; Walsh would pay the artist an undisclosed sum that included a monthly stipend for the rest of Boltanski's life in return for having his Paris studio fitted with surveillance cameras so that Walsh could watch and film him working. If Boltanski died within eight years, Walsh would receive the footage at a cheaper price. Walsh spent more than he anticipated, for Boltanski outlived Walsh's expectations by several years. However, Walsh now has an invaluable Boltanski archive.

Christiaan Boltanski died in Paris in July 2021.

Along with his wife Annette Messager, Boltanski rose to fame in the 1970s and 80s, particularly after his first Centre Pompidou exposure in 1982 in group shows, and a succession of exhibitions in events like the Venice Biennale (1980, 1993, 2011), Paris Biennial (1975), Sao Paulo Biennial (1983), Sydney Biennial (1979), and Documenta (1972, 1977). His first exhibition ever was at the Le Ranelagh cinema in 1968.

Boltanski had solo shows in prestigious museums, art spaces, and dealer galleries all over the world, such as the Centre Pompidou, Paris (2019), The Israel Museum, Jerusalem (2018), and the Noguchi Museum, New York (2021). His main agent was Marian Goodman, with whom he exhibited in Paris (2021, 2015), Goodman's Paris library (2019), London (2018), and New York (2007, 2001, 1995, 1991), but he also exhibited with other European dealers like Galleria Lucio Amelio, Naples (1993), Jule Kewenig, Cologne (1993), and early on, Galerie Ghislaine Hussenot, Paris (1989).

John Hurrell | Ocula | 2021