Mrinalini Mukherjee: Force(s) of Nature

Exhibition view: Mrinalini Mukherjee, Bagh, Jhaveri Contemporary, Mumbai (29 February–31 July 2020). Courtesy Jhaveri Contemporary.

Bagh, which translates to garden, is a fitting title for Jhaveri Contemporary's current exhibition of works by Mrinalini Mukherjee (29 February–31 July 2020). It was in the garden towns of her youth where Mukherjee developed a deep and enduring relationship with nature that charged her practice.

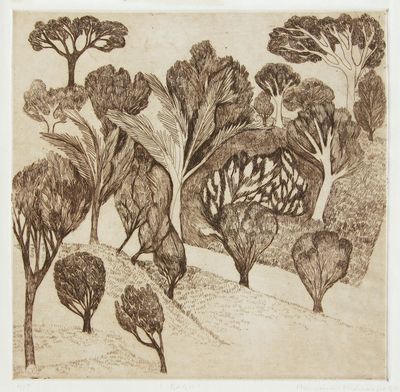

The exhibition marks the first time Mukherjee's early etchings and late bronze sculptures have been shown in conversation. The etchings were created in the 1970s and 80s at the Garhi studios in New Delhi and shown for the first time at the 2018 Kochi-Muziris Biennale. They depict vibrant woodland scenes that reflect the artist's formative years growing up between the foothills of the Himalayas in Northern India, and Santiniketan in West Bengal, where Mukherjee's father, the renowned artist Benode Behari Mukherjee, taught at poet Rabindranath Tagore's experimental art school Kala Bhavan, which celebrated nature and folk traditions in its independent curriculum.

A form of respite when Mukherjee was creating some of her most ambitious sculptures, these etchings seem to capture idyllic memories—like the wave of palm and chatim trees swaying in an undulating field in the 1984 print Bagh, which seems to look back at Kala Bhavan itself.

By contrast, Mukherjee's bronzes—which carry the influence of her mother, sculptor Leela Mansukhani—are abstract. They emerged in the early 2000s, when the artist began casting forms moulded directly in wax using the traditional lost-wax process, whose surfaces she finished with tools obtained from a local dentist. Bagh brings together nine such sculptures, made between 2006 and 2008.

Five of these sculptures are from the 'Cluster' series: forms that look as if they have been built up by broad, bronze leaves to create what look like vessels in the process of transmogrification. Cluster III (2008), for example, is grounded by the curves of an amphora whose shape is broken up by an upwards swirl of fronds that seem stirred up by the wind; while the gourd-like Cluster V (2008) appears frozen in metamorphosis, as an elegant neck curves upwards to suggest the emergent form of an eagle's head, and an open peel at the back recalls a tail-feathered curl.

Mukherjee moved on to bronze after experimentations in ceramics that started in the 1990s, with forms that echo those in Bagh. Take the partially glazed ceramic Flora (light) (2000), which shows tall elegant leaves curling around a refined, earthen vessel; or the glazed Flora Dark (2000), a receptacle in the process of fragmentation as it peels open into extended panels.

Both ceramic works were included in Transfigurations (27 January 27–31 May 2015), the artist's 2015 retrospective at the National Gallery of Modern Art in New Delhi curated by Peter Nagy, which brought the artist's fibre, ceramic, and bronze sculptures together for the first time.

In a moving tribute written after the artist's passing, Nagy, who met Mukherjee in 1997 at an exhibition of her ceramic sculptures at Vadehra Art Gallery, recalls installing her final work. Completed in the lead up to Transfigurations, he describes Palmscape IX (2015) as 'a gleaming bronze resembling the wings of a dragon, or perhaps a schooner aflame'—part of the 'Palmscape' series, which cast plant fragments into elegant forms. When the piece arrived in the gallery, Nagy writes, 'it seemingly levitated itself into position.'1

Given the impact of Mukherjee's 2015 retrospective, which was followed by the 2019 exhibition Phenomenal Nature at the Met Breuer in New York curated by Shanay Jhaveri (4 June–29 September 2019), Bagh's pairing of Mukherjee's realist etchings with abstract bronzes is inspired. It opens up another threshold through which to consider a multi-faceted practice, given the absence of Mukherjee's two-dimensional work in both surveys.

Bagh opened on 29 February with plans to move to Art Basel in June, only for Covid-19 to keep the show in Mumbai. The curatorial's intended destination makes sense when thinking about the adulation that Phenomenal Nature drew from an international audience—in particular, towards Mukherjee's inimitable fibre sculptures, crafted from rope sourced from Delhi markets and dyed with rich natural hues that Mukherjee knotted using her own frames and armatures to construct anthropomorphic and biomorphic forms.

...the filament illuminating Mukherjee's work is palpable. It is the invocation of nature's vital and constructive forces that connects every piece...

Each sculpture, often taking up to a year to complete, emerged from an intuitive engagement with the material; a process that filtered a fluid constellation of references that Mukherjee said came from all over the world. In the case of Yakshi (1984), whose name describes an ancient forest deity, folds of charcoal knots come together like chainmail. The work was made when Mukherjee's fibre sculptures hit their stride, with towering figures whose contours and crevices echo the armours of temple guardians, as well as costumes of Kathakali, Theyyam, Noh, and Kabuki performance.

The earliest work in Phenomenal Nature was a 1972 wall hanging, in which the three-dimensional qualities of the rope that Mukherjee used emerged in the form of a squirrel built out of the weave—a beautiful link to Afternoon (1979), one of the etchings included in Bagh showing a palm squirrel in a forest. In the print, we see the animal from its back, its nose pointing upwards towards the left side of the frame where the leafless branches of a tree lean right, along with the plumed forest behind it.

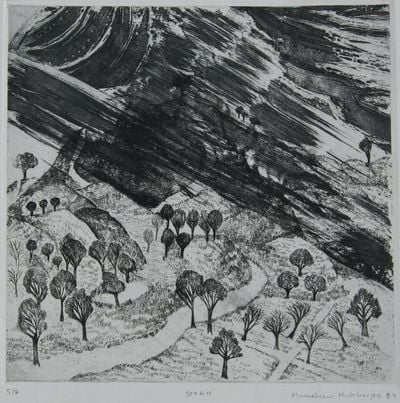

Like time-travelling messengers, these two squirrels open up a portal that connects Mukherjee's early etchings in Bagh with the textile works that she became so known for, through to the ceramics and bronzes that followed. When tracing her landscapes, whether the churning movement of palm leaves and brush in Midnight Lily (1980), or the rippling black strokes that cross over a meadow in Storm (1984), the filament illuminating Mukherjee's work is palpable. It is the invocation of nature's vital and constructive forces that connects every piece, united in their dynamic meshes of swirling lines, folds, and knots.

On works like Pushp (Flower) (1993), the artist's first fully freestanding sculpture, which inaugurated a series of fibre sculptures merging the floral and the vaginal, Mukherjee spoke about the semblance of the human form in her sculptures. She supposed they all 'started with the idea of a plant or some form of nature'.2 As the etchings in Bagh show, it really did always come back to the natural world for the artist, who took the role of conjurer and conduit of energies already in circulation to invoke a sense of awe, whereby a forest could be equated with a temple, populated by mythical beings and mortal bodies whose representations function as points of vivid contemplation.

But in this temporal spectrum that Bagh opens up, between prints recalling a childhood enthralled by nature and bronzes marking the culmination of an artistic path, something else comes through—the alchemy of tracing energetic recalls of situated memories; of leaving an imprint of something solid, a feeling of life itself, before it melts into air.—[O]

—

1 Peter Nagy, 'Passages: Mrinalini Mukherjee (1949–2015), Artforum, 22 July 2015, https://www.artforum.com/passages/peter-nagy-on-mrinalini-mukherjee-1949-2015-53885

2 Mrinalinee Mukherjee in conversation with Marjorie Allthorpe-Guyton and William Furlong, Audio Arts Magazine, Volume 13, Number 4 (1993)