Frieze London 2023 Artwork Highlights

Despite The Guardian's Jonathan Jones describing the fair as 'a graveyard of creativity'—taking particular aim at Damien Hirst's floral canvases as epitomising all that he felt wrong in the world of Frieze—a selection of works suggested otherwise, from a fossilised sofa by James Lewis at Nir Altman to a ghostly paint tray by Richard Hughes.

Left to right: James Lewis, Sediment (2023); 'Two Branches' (2023). Exhibition view: Nir Altman, Frieze London (11–15 October 2023). Courtesy the artist and Nir Altman, Munich. Photo: @graysc.de.

James Lewis, Sediment (2023) at Nir Altman, Munich

Nir Altman's booth was dedicated to the British artist James Lewis, whose work brought a hint of realism—and by extension life—to the picture-perfect fair. The decay contrasted with glossy paintings and rejuvenating skin therapies offered elsewhere under the same roof.

Lewis' Sediment (2023) comprises a mummified sofa covered with what appears to be a thick crust of dust and filth, upon which whisky glasses are placed in various folds. By materially ageing an environment associated with domestic comfort to the point of decay, the installation evoked the dissolution of the traditional family unit as a coherent and desired whole, where identities are not always inherited and safety is not always a given.

Three fossilised shelving units from the artist's 'Two Branches' series (2023) surrounded the sofa, each holding glasses with cast broken teeth and dried leaves, labelled with numbers and words that do not reflect their contents such as 'CopyCat' or 'Dolly'. In the context of the artist's background as a second-generation British Asian, they recall the unreliability of strict classifications and units of measurement as a proxy for making sense of complex realities.

Munem Wasif, Dark Water (2019) at Project 88, Mumbai

Project 88 presented a print installation by Bangladesh-born photographer Munem Wasif, whose work lined the outer wall of the booth, with evocative landscapes by Mahesh Baliga and small bronzes by Amol K Patil inside among works by other artists.

Wasif's Dark Water (2019) comprises 14 archival prints installed in two rows, in which the ocean appears along the top across seven ebony sheets. It is difficult to imagine what its expanses conceal until one reads the accompanying excerpts on the pages below, recounting experiences of exile and war.

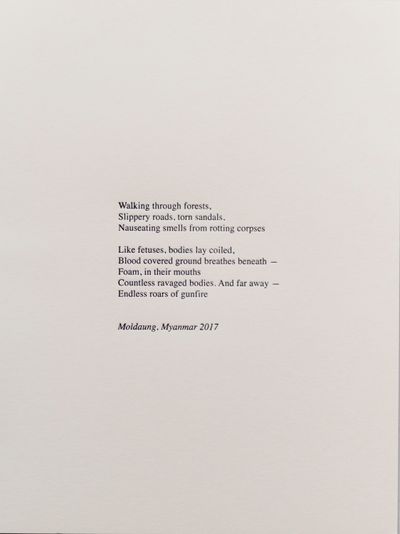

The work concerns the lives lost and the flow of migration in the Bay of Bengal, which over one million Rohingya people have attempted to cross in successive waves since the 1990s while fleeing persecution in Myanmar. One page dated 2017—when armed clashes broke out—reads: 'Walking through the forests, / Slippery roads, torn sandals. / Nauseating smells from rotting corpses.'

Samuel Levi Jones, Awareness (2023) at Galerie Lelong & Co., New York/Paris

Among a bright presentation of abstract paintings by Etel Adnan and Ficre Ghebreyesus and a work by Ana Mendieta documenting her green bodily form in a pool of water, was a painting of pulped law books by U.S. artist Samuel Levi Jones.

Jones is well-known for his material reconstructions, incorporating shredded dictionaries, medical textbooks, and the U.S. flag into paintings that challenge the accuracy and authority of commanding sources. Speaking to marginalised communities in the U.S. in particular, Jones highlights the information that may be left out when so-called truths are gathered from an institutional perspective.

Awareness (2023) is one such painting by Jones, made from shredded U.S. law books. The rough purple surface is dotted with uneven patches of red and blue, while a blood-stained bandage is sutured on the upper right of the canvas. Appearing to bear a kind of illness, the painting suggests that healing may begin with a revision of source materials.

Bram Bogart, Briques blanches (1992) at White Cube

White Cube brought their usual players to London with a group presentation, but one work quite literally stood out. Neither entirely painting nor sculpture, Briques blanches (1992) is among the late Bram Bogart's mature works, and the outcome of a fortunate crossover that enabled a unique blend of materials and processes.

From a young age the Netherlands-born Belgian expressionist had wanted to be a painter, but his parents urged him toward a practical career, leading Bogart to attend a technical school to train in house painting while taking drawing courses in the evenings.

Bogart initially explored figurative painting, and upon moving to Paris in 1946 after the Second World War, began working in a more cubist, expressionistic style. He returned to Belgium around 1959, where the materials from his early career would find their way into his built canvases. He started experimenting with three-dimensional paintings made from a mortar mixture. Constructed with the frame flat on the ground, they appear to counter gravity, taking the notion of a tactile painting to its extreme.

Richard Hughes, Laggardz (2023) at The Modern Institute, Glasgow

U.K. artist Richard Hughes' Laggardz (2023) is a reminder of the time and labour behind all great work, especially as many young artists are pressured to produce serial paintings of a similar style to be sold at high prices.

Sighted within Frieze London, Hughes' paint tray suggests that it is alright to experiment. The white residues of enamel paint inside the tray equally suggest a process of trial and error to arrive at one's own visual language.

It makes a strong statement, appearing rather aesthetic for what it is. A closer look shows tiny ghostly faces within the drips, suggesting the fear is ongoing, even when one has gallery representation and work at Frieze London. —[O]