The National 2021 Finds Ways to Care in Australia

Caroline Rothwell, Infinite Herbarium (2021) (still). Single-channel digital video made in collaboration with Google Creative Lab, high definition, colour, sound. Exhibition view: The National 2021: New Australian Art, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Sydney (26 March–5 September 2021). Courtesy © the artist. Photo: Jacquie Manning.

The National 2021: New Australian Art presents commissioned works by 39 artists from across Australia—from The Torres Strait to the capital Canberra—at three major cultural institutions in Sydney: the Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW), Museum of Contemporary Art Australia (MCA), and Carriageworks (26 March–5 September 2021; 26 March–22 August 2021; 26 March–20 June 2021).

Though 39 artists cannot represent an entire nation, the third iteration of this biennial exhibition makes inroads in addressing representation, equality, and understanding in an embattled sphere, with a cross-generational spotlight on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander, migrant, and women artists.

While each institution chose and curated its share of participating artists, curators worked closely to tease out a number of thematic threads. Most notably, the concept of care in the face of colonial dispossession and environmental degradation, with an emphasis on the handmade and collaborative, suggesting that hope lies in common bonds.

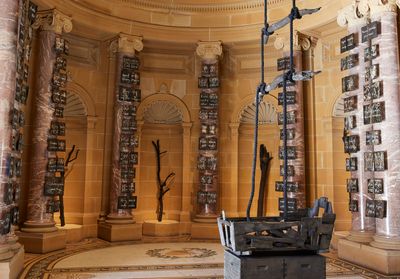

At AGNSW, a number of works organised by curators Matt Cox and Erin Vink reflect on social ecosystems and the frailty of nature, particularly in the face of man-made imposition, starting with Fiona Hall's EXODUST (2021).

Charred clothing, trees, birds' nests, and books, as well as a coffin and cradle, inhabit the gallery's neoclassical entrance vestibule: a requiem to the billions of organisms lost during the devastating Australian bushfires of 2019–2020. The placement of Hall's work in this space pits the incalculable loss of life against the cold intractable stone of the past with its colonialist ideas about display and ownership.

Gabriella Hirst's two-channel video installation Darling Darling (2021) continues the theme of care by comparing the lack of care for a living river and the care being lavished on a painting of it. One large screen shows the drought-affected and neglected Baarka Darling River in New South Wales, while the other details the meticulous work of AGNSW conservators' restoration of the painting The Flood on the Darling 1890 (1895) by WC Piguenit.

Extending the critique of Western value systems at AGNSW are works foregrounding Indigenous relations to Country, and the care that is infused in the transmission of memory as an embodied connection to land.

In Waanyi artist Judy Watson's clouds and undercurrents (2020–2021), draped and hanging pieces of cloth dyed with indigo and ochre comment on water degradation and the continuous rise of CO2 in the atmosphere, while two large collaborative canvases by Pitjantjatjara artists and ngangkaris (traditional healers) Betty Muffler and Maringka Burton, Ngangkari Ngura (Healing Country) (2020), picture ancient pathways of the emu and caterpillar with a nocturnal palette of grey, black, lilac, and cream.

The deep learning that comes with a connection to the natural world and its living communities is also foregrounded in Kala Lagaw Ya artist Alick Tipoti's large and colourful sculptures of the zugubal baydham (star shark) and the dhangal (dugong) in Dhangal Madhubal and Baydham (both 2021): objects that traditionally would have been produced to ensure successful hunts.

Behind these sculptures, the lively black and white wall-length linoblock, Seseren Aadhi (2021), documents the Kala Lagaw Ya people's enduring relationship with the sea through the telling of hunting stories passed down through generations.

Also drawing on both the past and the present to ensure the continuation of Indigenous histories is James Tylor's We Call this Place ... Kaurna Yarta (2020), a series of 25 daguerreotypes that disrupt the colonial process of photographing Aboriginal people and their land for ethnographic purposes.

Images of Kauma Country (now the city of Tarntanya/Adelaide), rather than of the people who once lived there, are each inscribed with words from the Warra Kaurna language, thus foregrounding the continuation of Country and culture.

Over at Carriageworks in Redfern, works by 13 artists and artist collectives curated by Abigail Moncrieff reference the dispossession of Indigenous peoples that has shaped Australia, and the neglect of its natural world in turn.

The call of the guwayi bird, heeded by Indigenous people over centuries as a herald of the rising tide, is at once a warning and a reminder in Vernon Ah Kee, Dalisa Pigram, and Marrugeku's large multi-screen video installation Gudirr Gudirr (2021). The work is an invitation to listen to history's lessons—and not only to the consequences of colonisation, but to testimonies of Indigenous survival and regeneration.

The contrast between Western and Indigenous uses of land and concepts of ownership is at the heart of Karrabing Film Collective's A Day in the Life (2020), with footage of two Indigenous men visiting an area poisoned by mining followed by scenes of them walking on pristine Country, recalling the elders who once gathered there for corroboree.

...The National 2021 celebrates difference as a means of inclusiveness during a watershed moment, when countries around the world, Australia included, are witnessing cultural and political upheaval due to the implications of inequality and environmental neglect.

Lorraine Connelly-Northey's installation Narrbong Galang (2021) confronts such degradation in object form. While the work's title references the 'string bags' that traditionally employ natural fibres, Connelly-Northey's bags are made from rusty, discarded metal often found littering the outskirts of country towns and farmland. Sharp and dangerous to handle, their installation in rows on the wall abstracts them into a series of coded objects.

Down at the MCA at Circular Quay, across from Sydney Opera House, Indigenous artist Maree Clarke extends the idea running through The National 2021: that culture is expressed in the act of making. Clarke's severe yet beautiful body adornments made from kangaroo teeth, echidna quills, and river reeds (the animal material gathered from roadkill) speak of respect for the natural environment, as well as the continuing of traditional culture.

Curated by Rachel Kent, the MCA exhibition is generous, with many of the 13 artists showing more than one work, often dispersed throughout the space. Caroline Rothwell's digital animations Carbon Emission 6, aperture; Carbon Emission 7 (both 2021), and Carbon Emission 5, Constructivist Rococo (2020), appearing in three locations around the gallery, cleverly reproduce the artist's concerns with climate change via their media. The animations started as paintings on glass made with carbon emissions collected from car exhaust pipes and soot from the 2019–2020 bushfires.

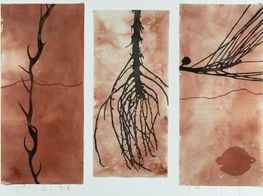

Another striking suite of works are those illustrating the internal workings of the termite nest or mound, an example of the long collaboration between John Wolseley and Indigenous artist Mulkun Wirrpanda, who passed in early 2021. One of these is Wolseley's Magnetic, arboreal and subterranean termite nests on the savannah plains of East Arnhem Land (2020–2021), a large multimedia multi-process work on paper, and Mulkun Wirrpanda's earth pigment on board works Pardalotes (2020) and Ŋäḏi ga Guṉdirr (2019).

In each artist's unique depiction, viewers witness not only the intricate workings of the termite's home and the ecosystem it supports, but each artist's differing ways of seeing.

The intricacy of difference is articulated, too, in a series of works that break down the rules around media and definitions of 'art' and 'craft'.

One of two works by migrant artist Mehwish Iqbal, Grey Wall (2020), for example, is made from 50,000 overlapping paper human figures that, from a distance, resemble a swarm of bees. In the face of Australian government policy and rhetoric around 'illegal arrivals' to the country, the artist maintains each hand-painted figure's individuality.

Meanwhile, Deborah Kelly has collaborated with a long list of creatives to produce a major body of work entitled Creation (2021), encompassing collage, filmmaking, embroidery, and tapestry that take the viewer on a dark ride through a 'temporal cathedral' where an apocalyptic future is challenged by a collective faith. If this edition of The National 2021 is about re-making and re-claiming the fraught territory that constitutes 'Australia', works like this suggest that it is through care and collaboration that healing takes place.

Of course, the idea of nation is a nebulous one—a construct that seeks to bind people together through the hope that shared values outweigh disparate ones.

Conversely, The National 2021 celebrates difference as a means of inclusiveness during a watershed moment, when countries around the world, Australia included, are witnessing cultural and political upheaval due to the implications of inequality and environmental neglect. The National 2021 is rightly part of this conversation. —[O]