Diana Campbell Betancourt

Diana Campbell Betancourt. Photo: © Pablo Bartholemew.

Diana Campbell Betancourt. Photo: © Pablo Bartholemew.

Diana Campbell Betancourt is a curator working predominantly across South and Southeast Asia.

Since 2013 she has been the founding artistic director of the Samdani Art Foundation and chief curator of the Dhaka Art Summit in Dhaka, Bangladesh, a transnational art event that has grown in size and scale ever since its first edition in 2012. Backed by the collector couple Nadia and Rajeeb Samdani, the Samdani Art Foundation first initiated the Dhaka Art Summit to register the Bangladeshi art scene as distinct from India.

Upon joining the team Campbell Betancourt overtook the conceptualisation of this event and initiated numerous further programmes, including the Samdani Seminars, Samdani Art Award, and the Samdani Artist-Led Initiatives Forum, as well as partnerships with institutions around the world to tour exhibitions that were born in the Dhaka Art Summit.

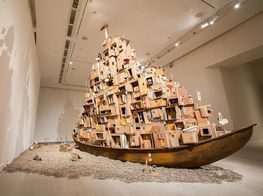

Furthermore, they are ahead of opening their first permanent space: Srihatta–Samdani Art Centre and Sculpture Park in Sylhet, dedicated to large-scale and long-term experimental commissions and residencies by artists such as Asim Waqif, Haroon Mirza, Ayesha Sultana, and Superflex.

Campbell Betancourt established the Dhaka Art Summit as a research and exhibition platform that goes beyond the logic of a one-time or time-specific event, stressing the continuity between its consecutive editions, and openness towards different publics. The summit recurs every two years at the Shilpakala Academy—a state-sponsored national cultural centre of Bangladesh and a place that the local public is familiar with, and feels comfortable visiting.

In 2018, the summit attracted over 300,000 visitors, hosted ten curated shows, as well as intense discursive and educational programmes that connected the dots between different themes within the exhibitions. With Campbell Betancourt, the summit also started to prioritise new artistic commissions, which include Munem Wasif's series of photographs and videos 'Land of Undefined Territory' (2014–2015), a second chapter of Po Po's 2010 VIP Project (Yangon), Reetu Sattar's Harano Sur (Lost Tune) (2017–2018), and Shilpa Gupta's work on India-Bangladesh enclaves, among many others.

As an advocate of in-person interactions, Campbell Betancourt tries to foster opportunities for cross-cultural encounters in public space. Until 2018, she ran Bellas Artes Projects, a non-profit international residency and exhibition programme with sites in Makati City, Manila, and Bataan, where she curated Bruce Conner's first major solo exhibition in Asia across both sites (Out of Body, 24 February–3 June 2018), as well exhibitions of new work by artists such as Pawel Althamer, Cian Dayrit, and Isabel and Alfredo Aquilizan.

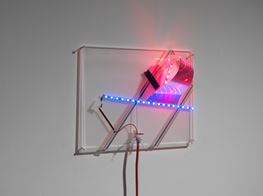

In 2018, she also served as the curator of Frieze Projects in London, where she worked with artists such as Julia Scher, Laure Prouvost, Pratchaya Phinthong, Liz Glynn, Christian Boltanski, Camille Henrot, Otobong Nkanga, among others, on site-specific, time-based interventions that were responding to the dynamic flows of information within the fair, and the relation between the visible and the invisible. Guards, Hidden Camera by Julia Scher, for example, engaged a pair of mature women dressed in Scher's signature pink uniforms, who were interacting with the audience, while a set of security cameras were embedded in an accompanying installation. Liz Glynn realised a work entitled The Fear Index, in which dancers moved in response to art market information and the volumes of people coming in and out of fair.

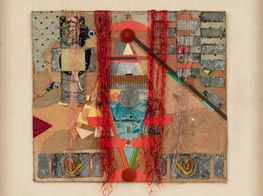

Fabric(ated) Fractures, curated by Campbell Betancourt, will be on view between 9 and 23 March 2019 at Alserkal Avenue in Dubai, showcasing works by Bangladeshi, South Asian, and Southeast Asian artists as an extension of the exhibition There Once Was a Village Here that was held at the Dhaka Art Summit in 2018. The show complicates approaches to looking at art from the region, speaking to DAS's wider aims of rewriting art history and building radical solidarity across the Global South. Campbell Betancourt discusses the exhibition, among many other endeavours, in this conversation, which took place during a rare break from travelling at her personal headquarters in Brussels. I caught her surrounded with books by Walter Mignolo, Donna Haraway, plus 'Teach Yourself Bengali: Complete Course'.

MBCould you tell us what influenced your practice as a curator prior to becoming one?

DCBVisiting museums was a core part of my school curriculum and some of my earliest memories are of LACMA [Los Angeles County Museum of Art] and the Getty Villa, where I learned about the lasting power of art and the conditions necessary to share it with the public in Western contexts. I think something that definitely had an impact on the way I work is that I am trained very seriously in classical ballet. From the time I could walk until the age of 17, my single dream in life was to be a professional ballerina. The experience between the body, space, and music is something that definitely primes the way I look at exhibitions or even put together large-scale events like the Dhaka Art Summit.

There is something choreographic about the way I think—I feel the body relative to other bodies and other objects in space, and I am interested in how these relations change as one moves. Dance also shaped me in terms of being patient and disciplined. Curating, like dance, is an everyday practice for me; you cannot just expect to suddenly be able to achieve certain things without daily work that transforms the way your mind and body are able to connect, like finishing 32 perfect consecutive fouette turns. In ballet, intense training makes what seems impossible possible, and I can say the same for planning an event like Dhaka Art Summit in a country with little to no infrastructure to host exhibitions of this nature.

Another thing that has influenced my curatorial approach—especially in the context of the Dhaka Art Summit—is that I volunteered for the Clinton Foundation as a young adult, which is a platform where people with political agency, entrepreneurs, and high net worth individuals and investors come together in order to make commitments to tackle major societal challenges such as climate change, hunger, and so on.

That is something that I try to do at least with my work within the Samdani Art Foundation, that is to create opportunities where people can come together and make a difference based on talents, agency, and resources that they have, creating the conditions for great art and conversations about it that are born in Dhaka.

MBWhich values guide you as a curator?

DCBWhile acknowledging the importance of getting out of human-centric thinking, I believe in the creative potential found in human interactions and generosity of knowledge within those interactions. Raqs Media Collective once gave me the following advice: surround yourself with people who are generous with knowledge because if you tell someone something that you know, they will tell you what they know, and then you both will know more than twice as much.

I believe artists are generous when they are sharing their work and ideas. The question for me as a curator is how to share those ideas with a wider and more diverse audience, allowing these ideas to be read in new ways, but without instrumentalising the artworks.

MBBetween 9 and 23 March 2019 you will present the group exhibition Fabric(ated) Fractures at Alserkal Avenue in Dubai. Could you tell us what your motivation is behind this show?

DCBThere is a regional acronym that is often thrown around in the context of Dubai and Bangladesh: MENASA, which stands for Middle East, North Africa, South Asia. What would probably be expected from a show of a Bangladeshi foundation that has a regional platform like the Dhaka Art Summit would be to do some kind of MENASA show, but there are a lot of things that get lost when you look through a national framework like Bangladesh, or a regional framework like South Asia, or another framework like MENASA. Bangladesh is on this slippage between South and Southeast Asia, and there is no regional buzzword to talk about the space between Bangladesh, Myanmar, and Thailand beyond Zomia.

Through the show, I wanted to complicate the way that people might look at the culture that comprises Bangladesh. There are at least 42 languages other than Bangla that are spoken in Bangladesh. The word 'fabricated' within the title of this show points to these strands of difference that come together to form the yet to be crystalised identity of a country that is less than 50 years old. The show looks at voices that tend to get drowned out in the search for a 'common denominator' of a shared majority identity, and it also shows many artists who do not have commercial gallery representation and whose work therefore is not included in many international exhibitions.

There are beautiful works by artists from Bangladesh, India, and Nepal in this show that poetically speak to the struggle to hold on to indigenous language and cultural heritage in the face of violence and displacement. The show primarily draws from the Samdani Collection and our past commissions of the Dhaka Art Summit from 2014 to 2018, and I think it beautifully shows the inspiring commitment of Nadia and Rajeeb Samdani, the patrons behind all of the great work we do in Bangladesh.

MBAt the same time, you are working on the fifth edition of the Dhaka Art Summit. Having experienced the ambition and complexity of the previous edition I am curious what is on your agenda for 2020? How will you build up on what you have already achieved?

DCBAs already mentioned I see problems with regional frameworks, so I find it important to open up this upcoming edition of DAS to look at connectivity across the 'Global South', based on shared struggles rather than geography. Bangladesh has been 'international' long before Western colonisation. Inspired by the 1414 gift of a giraffe by the Sultan of Bengal to Emperor Yongle of China, this summit will widen its view to look at historical layers of connectivity across Asia and Africa and the Indian Ocean and catalyse further exchange across these regions without Western intermediaries.

This summit is also very inspired by ideas of Pangea and plate tectonics, Latin America, the poles of the earth, and other parts of the planet that one might not expect to be in connection with Bangladesh, which will be present through the artistic programme of DAS 2020. So, the fifth summit will be looking at seismic shifts in the world, be they geological, political, or social, in the hope that it can act like a seismic shift in itself to catalyse movements, and that we—curators, artists, academics, and the general public—can all be part of that movement.

I started thinking of DAS rather as a movement, since over 300,000 people come back every two years and it is a cumulative exercise of sharing and building knowledge and community together. Movements happen on different scales, and they have changed the way we experience the world now. Bangladesh was built by students with conviction. These student movements, beginning with the language movement in 1952 when students protested the colonial language of Urdu, replacing their native language of Bengali as the official one, led to its struggle for independence in 1971. We are standing on the backs of these movements. This will be the first Dhaka Art Summit with a title: Seismic Movements.

At the same time, the upcoming summit will take a more academic turn. While the past Talks Programme has been mainly industry-focused, with a lot of curators and museum directors speaking, this time it will be purely art historical, as I think there are a lot of gaps in knowledge in terms of art historical narratives.

MBI find it interesting that the summit expands its educational programme with each edition, which I feel is a broader tendency and can be seen with the proliferation of the public programmes within recurring large-scale exhibitions in general. Could you tell us more about the collaboration with the Getty Foundation and elaborate on the idea of filling the gaps of art history?

DCBWe have had meetings about this programme since 2017. In the previous editions of DAS, I saw that there is a huge gap between practicing art professionals and art historians, and that there is a lot that can happen if these two groups come together. Through this programme, we also want to get outside of nationalist framing of histories in a world where nationalism is rising nearly everywhere. We received a Connecting Art Histories grant from the Getty Foundation in collaboration with the Institute for Comparative Modernities at Cornell University and Asia Art Archive in Hong Kong.

This will allow us to bring 20 emerging historians of art and architecture to Hong Kong and Bangladesh for a year-long itinerant comparative art histories research project. So, it is not just about the nine days in Dhaka—we will first meet in Hong Kong in August for 11 days, then we will have distance learning sessions, and then the scholars will be in Dhaka for 11 days during the summit.

I also think the summit is a great place to discover and listen to new voices, and I am hoping that we can catalyse visibility and opportunities for these scholars. What is also great about the Getty grant is that it is not about publications—they are really trying to foster an unprecedented meeting of minds, and I am really excited about what might come out of this. Thinking about seismic shifts, I believe we will see the effects of this in about 20 years.

MBYou think very long term, but in times when political changes are happening so quickly, how can you act in time?

DCBYou plan, you revise, you plan, you revise. It is true that something unexpected happens every single time. After the Holey Bakery terrorist attack in 2016, we were not even sure whether we could continue making the summit in Dhaka, so we were exploring moving it to another country, and took this discussion pretty far. It is important to have multiple plans, because you never know.

Artists are really on the pulse of what is happening in the world, and I try to work on their time. My commitment to artists is to their work and projects, not to the immediate exhibition at hand. For example, I am still working with Lucy Raven on a film project related to the eruption of Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines even though I no longer work at Bellas Artes Projects, and this work is not tied to my institutional platforms. The film grew in scope and scale and we realised it didn't make sense to rush it for the flashpoint of an exhibition whose date was fixed and could not be moved, and we worked together to rethink the right time and context to bring it into the world while still meeting our commitment to create a meaningful exhibition.

I lived with artists during my two years at Bellas Artes in the Philippines, and I learned that I cannot always hold artists to my exhibition timelines because it can actually hold back the creation of a masterpiece. I cannot wait to have the residency complex ready at Srihatta—Samdani Art Centre and Sculpture Park, because there we can have a different sense of time with long-term experimental projects that are not geared towards an opening date the way DAS or BAP exhibitions are.

Rather than just focusing on the flashpoint of an exhibition like DAS, and inspired by the words of my colleague Koyo Kouoh, I wanted to give focus to the practices of artists, curators, and professionals who build the conditions for the art that we show in exhibitions to be made. DAS can contribute to improving these conditions by bringing people together and opening up new collaborations, which can allow for sharing of resources and reimagining of solidarities outside of soft power or geopolitically motivated channels.

To this end and in a forward-thinking manner, we are bringing over 30 collectives from Bangladesh and the Global South together in Dhaka for the summit for an exhibition of their work, but also in-person meetings and workshops about institution-building, curating, and working collectively. The results of this and the Getty programmes will not be able to be evaluated within the nine days of DAS; they will become visible in the decades to come. I don't think about the event itself—I think of what an event can catalyse for the betterment of the everyday.

MBI know you are a very climatically aware person—what are the biggest challenges that you face in terms of ecological responsibility?

DCBOf course, I have to deal with the carbon footprint of all my travelling—something that is necessary to build DAS. Right now, we are actually working on an exhibition design think tank supported by Pro Helvetia, putting equal focus on exhibition unmaking as we do to exhibition making. We are analysing the climate footprint of the summit to come up with ideas of how to reduce it through design elements.

I do think that being climatically responsible is important, but I am not thinking about a cut on flying people in, because I believe that those in-person meetings are very important. At the same time, I think there are certain artworks that are very important to have for the discussions we want to raise, but is the shipping of them climatically responsible? So, there are ethical dilemmas that I have to grapple, and choices I have to make in the end, and I am aware that some of the funding for the summit might be tied to things that are not ecological, so it is a contradiction, but these contradictions are everywhere in life and you have to deal with them.

I am feeling the immediate effects of climate change now. As I was visiting Shilpakala Academy with my team of exhibition designers, Bangladesh underwent unprecedented rain in February. Bangladesh used to have six seasons, it now has less than three. We never had to factor in rain to our exhibitions as DAS does not fall in the rainy season; we now do and the entire DAS 2020 exhibition is being reconceived spatially to factor in this climactic shift.

MBLast year you also worked as a curator of Frieze Projects—how does your practice there relate to your work within the summit, if it relates at all? Which curatorial values do you implement in the context of Frieze, which is so different to Dhaka?

DCBI think my experience with DAS helped my work in Frieze because of the ability to imagine space when it is not there—both DAS and Frieze happen in spaces that are temporarily constructed for the event. My experience of building space within space is also helpful. It was good for my imagination to be able to remove myself from a regional framework.

I learned a lot working in the context of the Frieze, which is so different to Dhaka, because while there is far more infrastructure to support the projects in London than there is in Dhaka, there are different kind of rules to navigate, such as limited decibel levels allowed in Regent's Park. Like in DAS, I tried to create a programme that is diverse across race, gender, and age, and the fair has been extremely supportive in this endeavour. Some of the artists I work with for Frieze are also working on projects with me for Dhaka, such as Otobong Nkanga.

Working with the same artist across different platforms helps me get closer to their ideas rather than having our exchange be geared towards one specific context. I am enjoying the process of curating the 2019 Frieze Projects programme and bringing my dance background into the programme. It was great working with Polish artist and choreographer Alex Baczynski-Jenkins on the Frieze Artist Award in 2018, and it got me interested in looking at the space where art and choreography intersect. This interest extends into the next DAS where we will also be showing the work of William Forsythe, whose practice speaks to bodily responses to the constraining conditions that politics have thrown us into.

MBWhat are the biggest challenges that you face?

DCBGoing back to the idea of language and how it programmes you—I want to learn Bangla and I am trying to do so. It is really challenging to find the time to do this when I have to problem solve in English for the vast majority of my day. I learned Mandarin in college and gained agency over the language by total immersion during summers in Beijing, so I think a similar immersion experience is going to be necessary in Bangladesh and hopefully this can happen once Srihatta's building is open and I can create a Bangla language residency for myself in the company of Bangladeshi artists. Our first residency cycle will be with Samdani Art Award shortlisted artists in 2019, so this is just around the corner.

MBHow do you self-evaluate?

DCBSomeone told me that I am not driven by success, but I am driven by a fear of failure—I am an extremely self-critical person. I take my responsibilities extremely seriously. I stress it again and again that Dhaka Art Summit is not about the individual editions; it is a continuation, and it always builds on the last one, so seeing how it evolves over time and what kind of collaborations it fosters is for me the result of constant self-evaluation. The latest takeaway from self-evaluation is that I need to stop constraining my professional thinking to English, and I look forward to seeing where this insight takes me.

I believe that an empathy for other cultures comes into play when you don't fit into one. I am bi-racial: my maternal family is indigenous Chamorro from an island called Guam, a U.S. territory that is technically one of the last 17 colonies left in the world, while my paternal side is of Scottish-American origins. I still get comments at least once a week about how I do not look American, and I also grew up thinking in a different language than most people around me.

My first words were actually not in English, but in Spanish, because when I was a young child my mom had a very rough pregnancy with my sister, she was not around much during the time when language began to form, and I spent a lot of time growing up with my nanny Carmen from Mexico, who I am still very close to thanks to the connectivity of WhatsApp.

I can still flip in and out of Spanish and sometimes I dream in Spanish. When you are young it's rather hard, because kids are looking for groups and sameness, but now I think it actually fostered an ability to understand the spaces between cultures, and to understand difference, and to not be constrained by a world you are born into but rather to find ways to make new ones. —[O]