Hassan Khan’s Systems of Associations at Centre Pompidou

© Hassan Khan 2022

© Hassan Khan 2022

Hassan Khan would underline that he is an artist, musician, and writer in no particular order. 'My medium is not the medium itself' he has said. 'My medium is how I approach these mediums'.1

That approach, in which the medium becomes the subject, is most evident in Khan's work with music, for which he has explored the genres of Shaabi—a popular Egyptian musical genre whose name translates to 'of the people'—the Indigenous Javanese and Balinese orchestral music known as Gamelan, and hip-hop.

For the 2005 light and music installation DOM-TAK-TAK-DOM-TAK, six recordings are the product of Khan's analysis of six Shaabi standards. First, he studied the generic rhythms of each song, isolating and rerecording them with a percussion section. Then he hired session musicians to each play within set keys and over each of the recorded beats without hearing one another.

These recordings were then mixed and mastered into six instrumental tracks that combine the algorithmic nature of popular music, in which codes and methods are transmitted as programmed memory, with deviations of individual interpretation from within this programmatic culture.

That hybridity extends to Khan's system of taking elements that he pre-records in order to transform them into live situations using a feedbacking mixer, which Khan notes produces a certain amount of chaos.

When introducing Club Gamelan in 2015, which filters elements of a computer programmed gamelan orchestra through the language of minimal club music, Khan described a dialogue between chaos and disorder in the live filtering of pre-composed music with the 'breakdown' of a live feedbacking mixer.2

The result in the case of Club Gamelan, is a hypnotic, transcendent, and unrelenting composition with ebbs that echo Philip Glass and Steve Reich, and flows that blend spheres of techno, microhouse, and psychedelia across the ages.

In a way, Khan's engagement with musical forms is about pushing genres to their edges to find out what happens after the breach—an engagement that always results out of a collaboration between Khan as the composer and the musicians he works with.

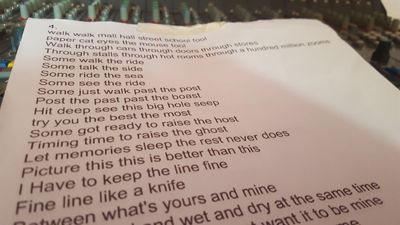

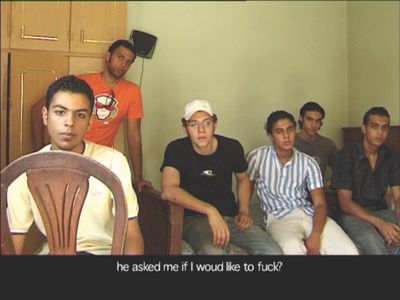

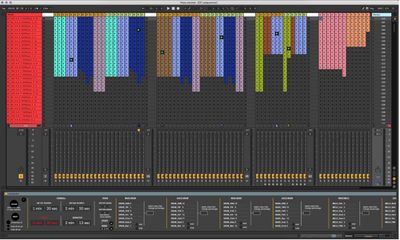

The Infinite Hip-Hop Song (2019), conceived as a never-ending hip-hop track that never loops, follows this same logic. Pre-recorded elements based on Khan's beats, baselines, melodies, and lyrics combined with rapping sessions produced from ten days working in the studio with 11 rappers resulted in over 800 vocal samples.

At once bound and displaced by its programming, exports of The Infinite Hip-Hop Song function as sessions that always manifest differently whenever the program is run.

The Infinite Hip-Hop Song was first shown as part of The Keys to the Kingdom, a solo exhibition organised by the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia at the Crystal Palace in Madrid (18 October 2019–1 March 2020), which presented a new body of work that responded to a former World's Fair location.

Among the interventions were a series of brightly coloured banners that hung from metal poles of different heights, each featuring an icon designed by the artist that draws connections to cultural symbols, such as Boris Johnson's unmistakable Trump-adjacent blonde hair.

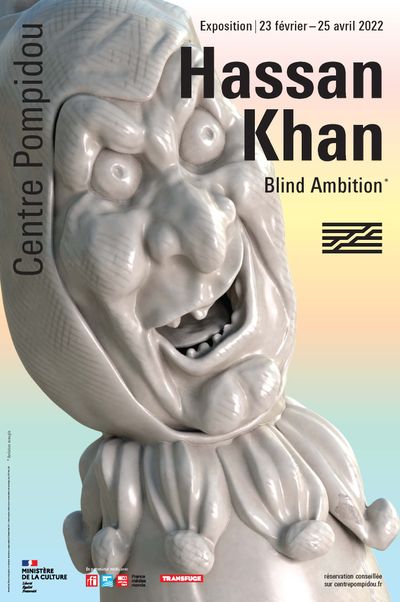

The Infinite Hip-Hop Song was then included in the group shows Soft Power at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in 2020 and Liquid Love at MoCA Taipei (14 November 2020–24 January 2021), and forms part of the artist's selective survey at the Centre Pompidou in Paris, Blind Ambition (23 February–25 April 2022).

In this conversation, Khan introduces Blind Ambition and the remixes of old and new works that take place in an exhibition conceived as a landscape. What emerges is a logic that runs through the artist's practice, in which culture—both its instruments and its instrumentalisation—is the object of study: a score that never finishes.

SBCould you introduce your survey at the Centre Pompidou?

HKThough Blind Ambition falls within the framework of a selective survey, I imagine it more as a shifting landscape. The entire exhibition is installed on a series of wood platforms of different sizes and heights connected by ramps. Every platform hosts a constellation of works.

When you first enter the exhibition, you are offered a panoramic view of these different constellations. Something that deceptively might seem to be reducible to one totalised whole, but is actually a tapestry or network of different impulses. A sort of a snapshot of my practice.

It's a bit like the exhibition trailer, where disparate details from the exhibition are engaged in a hysterical neurotic interplay yet are held together by the insistent driving beat of a 2005 piece titled...wait for it...Blind Ambition.

But then as you, the fantasised audiences of my imagination, begin to traverse this landscape, you may experience each constellation as a discrete unit, an island within an archipelago, with its own logic, set of relations, and impact. You may be caught in the details of each stage but hopefully you may also be able to zoom out and engage in placing these sets in relation to each other. To see how these groupings of very different types of work echo, resonate, contradict, and clash.

At the heart of this play with association and juxtaposition is an inner dialogue between the pieces: multiple threads running through over 20 years of production and a basic understanding of the work as something beyond meaning.

Hopefully this allows for a sensitivity to these multiple registers. The work is content, it is dynamics, texture, narrative, implication, and affect amongst many other things. My ambition is to be able to play with all of this—to have my cake and eat it. My ambition is to offer enough for viewers to invest themselves in the process without giving up what I, in any case, have no control over.

I must also mention Marcella Lista, the curator of the exhibition who was instrumental in supporting and discussing how this approach works in relation to a survey that tries to frame an artist's practice to audiences that might not be very knowledgeable about the artist's work.

Lista's deep and profound understanding of art history coupled with her hands-on experience of contemporary art has helped this conversation grow and deepen and for these propositions to be be transformed into an actual exhibition.

SBCould you describe a constellation of works that appears on one of the exhibition's platforms?

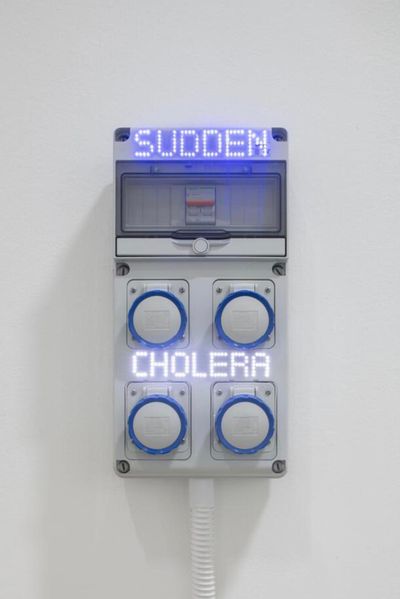

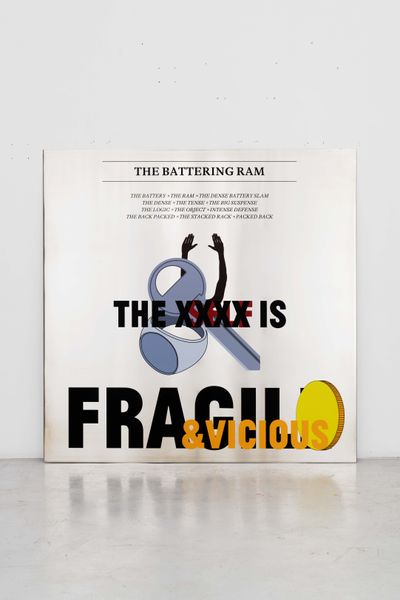

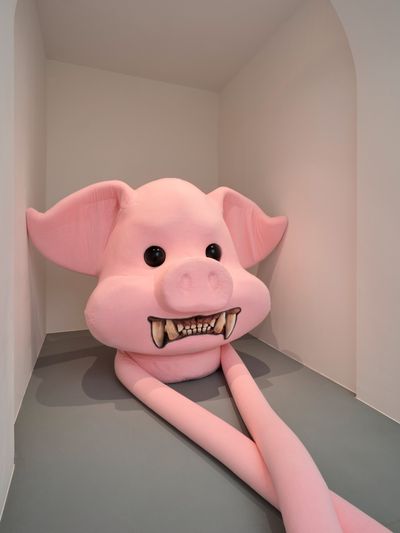

HKThe second platform, which is quite dense, includes seven works: I am not what I am (diagram) (2007); stuffedpigfollies remix (2007–2021); Purple Stuffed Creature with Bleeding Eye (2019); Evidence of Evidence II (2010); My Mother (2013); The Self is Fragile and Vicious (2021); and SUDDEN CHOLERA (2018).

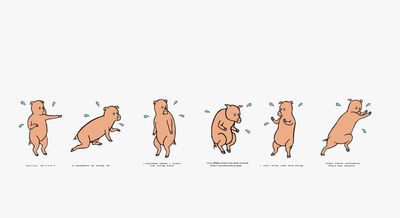

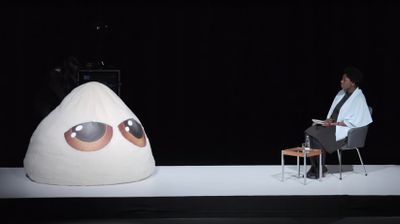

These seven works on this platform try to put two contradictory impulses in dialogue. There is the strange haunting anthropomorphism represented by stuffedpigffollies—six large cut-out vinyl prints of basic computer-drawn Disney-like pigs in a state of anxious contortions applied to the wall—and Purple Stuffed Creature with Bleeding Eye, a large creature that looks like its title. Both produce a sense of identification and distance—both want to be loved yet allow for more complex emotions than solace.

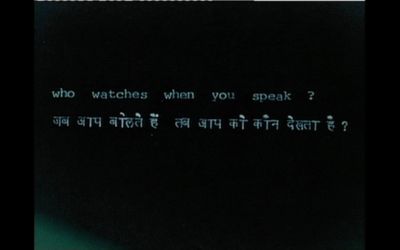

Projected on a suspended screen in the space is I am not what I am (diagram), an animated grid; a structuralist work that translates an algorithmic logic into a diagram that demonstrates itself and a simple illustration of the mechanisms of self-consciousness. Though the mess of emotional identification is contrasted to the cold logic of the algorithmic and what it produces, these works are very much about the impulse to produce an image of the self.

Then you have My Mother, which is a cell phone portrait of my mother that I took after six years of hesitation. I believe the portrait is both hostile and intimate in a way that reflects how those closest to us can be our harshest mirrors. That, to use old fashioned words, love and alienation are intertwined.

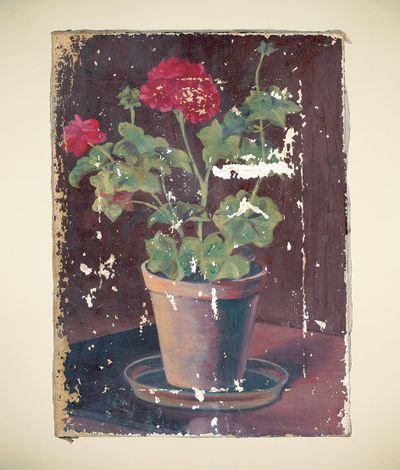

Evidence of Evidence II changes gears and introduces the historical as well as a sense of materialist objectivity into this conversation; a found damaged generic oil still life of geraniums has been transformed into something that flirts with the sublime.

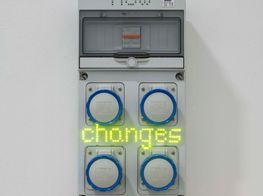

Finally, in SUDDEN CHOLERA, one of four of the modified electricity distribution boxes of Sentences for a New Order that are on show in the exhibition, automated LED lights flash in a way that echoes I am not what I am and call forth the infrastructure of the world as we know it.

SUDDEN CHOLERA resonates with the forensic impulse of Evidence of Evidence II, and presents the possibility of collapse endemic to our construction of self that is latent in the rest of the works.

I am, of course, making things up and explaining fictions, but my own private investment into the constellation is necessary for the work to exist in this form and to be presented. I believe this investment is what allows audiences to discover a position for themselves in relation to the work.

Maybe we are all caught in some kind of transaction, even if it is not the same one for all of us. For me, realising that and working with it is a proposition, and ultimately, a politics.

SBHow does this relate to the way you normally stage your solo exhibitions?

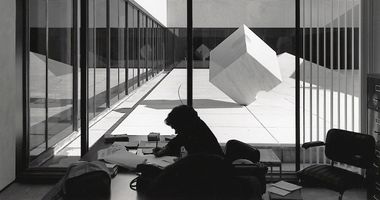

HKI usually put exhibitions together very carefully, but also very intuitively. I never build scale models and almost rarely use computer models.

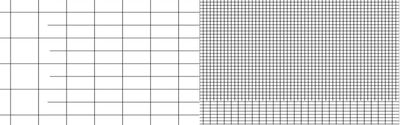

I visit the space, take photos, look at the floorplan, and imagine how things could be arranged. I work with designer Engy Aly on the plans using a tape measure and the scale of the room I am in, usually her studio in Cairo, to extrapolate the scale of the work. Then I work out the rest during installation. For Blind Ambition we used computer models because the complexity of designing the landscape necessitated it.

However, there is something quite exciting in this kind of jump. The fear of complete failure and the pleasure of trusting something that has been accumulating for years. It would be easy to call it experience so I won't. 🙂

Intuition is not mysterious but rather an automated inner voice that has been absorbing everything I have ever experienced, and transforms this material (anthropomorphically no less) into a sort of fluid inner character that 'I' am in dialogue with. A bit like the 27 voices that speak through the three avatars of The Dead Dog Speaks (2010), which is also on show in this exhibition. That is a productive fiction.

I'm also treating this show like a music album, but not metaphorically. There are opening tracks, hits and codas, epic blowouts, and short lyrical songs. There are works that I'm thinking of as remixes, and of course there is a very conscious rhythm to the whole exhibition.

In the remixes, I have taken elements from older works and put them together in new formats, while sometimes older works have mutated into something new, like an old track being revisited.

SBDo you have examples of how these remixes manifest in Blind Ambition?

HKStuffedpigfollies, which was first produced in 2007 as simple 20-centimetre computer prints on Canson paper, have been blown up into large vinyl prints directly attached to the wall. So now you have these one-metre-tall raw cartoon pig characters sort of anxiously dancing in the space.

The Alphabet Book (2006), which was originally a book, is here displayed on a structure where 52 images and letters are shown side by side. It is now both an actual object in space as well as a display structure.

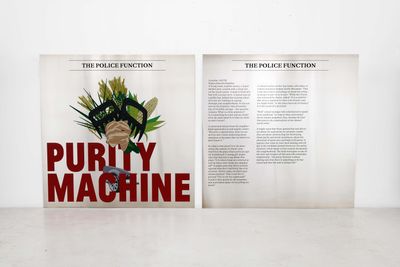

I'm also literally remixing the icons I designed for the banners I made for The Keys to the Kingdom, the show I staged at the Reina Sofia in 2019. I've isolated these icons from their original context and recomposed them into new figurations and had those printed on large aluminium plates alongside authored song lyrics, headlines, slogans, and quasi-journalistic reports from the frontlines of what I call the police function.

I see these pieces as 'object broadcasts'. There are three of them with three headlines, slogans, or titles—Purity Machine, Harvest of Guilt, and The Self is Fragile & Vicious—each one includes a different sort of text. One has a song, the other is written in the style of a newspaper investigation, but it's sort of a psychic investigation, while the other is a kind of rhyming riddle.

SBCould you talk about the banners for The Keys to the Kingdom that you have extracted symbols from?

HKYes, in The Keys to the Kingdom there were 16 banners in total, 12 are double-sided in the sense that they have different icons on both sides, and four in the middle have the same signs on both sides.

Part of the formal aspect of those designs was site specific and had to do with inhabiting the space they were in. The Crystal Palace is a large airy glass and steel structure in the middle of a public park. The banners are big, colourful with clear bold emblems so people could actually see them from quite a distance outside the Crystal Palace.

They're broadcasting from the space to the world, and they draw people in. When people come and enter the space and walk through them, they become a bit like a labyrinth of signs. Each flag and its icon were designed in relation to each other so that you see it as a network of associations, depending on which side you look at, and how you walk through the space.

I'm also treating this show like a music album, but not metaphorically. There are opening tracks, hits and codas, epic blowouts, and short lyrical songs. There are works that I'm thinking of as remixes...

There's that formal aspect, but from a conceptual perspective the idea was to create icons that are accumulations of contemporary emotional landscapes: desires, fears, projections. They are sublimations, not symbols. I don't think they stand for what they refer to as such, but they emanate the emotional landscapes they arose from. They are symptoms of symptoms.

So, we have gestures that express emotions like the raised hand, which of course comes from both protest and surrender or the clasped hand of supplication or thanks. We have elements like Boris Johnson's hair, a grotesque sign bearer of how power can accumulate in the 21st century, or bear claws exuding latent violence.

We also have magical objects like blank coins and keys, a wooden mask, chrome finished car headlights, and composite mechanisms like the bleeding eye, which also appears in Purple Stuffed Creature with Bleeding Eye.

SBSpeaking of symptoms of symptoms, it is interesting to see Pepe the Frog among the icons.

HKBut it's not just Pepe. It's Pepe hybridised with Crazy Frog, the computer generated character who marketed popular mobile phone ringtones in the mid 1990s. I was totally fascinated by Crazy Frog when it came out because of its strangely banal yet haunting anthropomorphism, the power of animation, that crazy dance and tune. All these made that gesture potent.

The anthropomorphic gesture is one of the threads that run through the whole show, as with our childhood teddy bears, it is about how and what we invest in them.

Whatever it is, we definitely invest something into these inanimate things and are thus able to grant them the inner life that we project into them. As a teenager I once spent a whole night tripping out on Parkinol and chatting with my childhood teddy bear.

That's what really struck me about Crazy Frog when it came out—how it was centred on this zany character, but it was really about marketing ringtones. It became a clear symptom of this specific financial turn—the idea that a ringtone could be an expression of some kind of emotional self that is connected to others. Mind you, this is not a critique—it is an observation.

Pepe the Frog was also interesting in that sense, because of how it was immediately appropriated by hatred. But also, I don't want to use the word appropriated merely negatively. I think appropriation is a real and basic constantly ongoing cultural operation, and in any appropriation, there's always something that makes it potent and makes it able to function as a glue for political capital.

We need to understand this if we are interested in producing works that do not merely parrot the doxa of the day; that also offer actual propositions that are not fantasies of what is constructed as 'correct' but rather conflicted and living engagements with the real.

SBWhat you said brings to mind the concept of meme magic, which became associated with Pepe the Frog, and this belief that the meme was responsible for bringing Donald Trump into office.

HKYes, exactly. That was part of the thinking behind the emblems of The Keys to the Kingdom. In this case specifically, I am using a composite of two related yet different images—metonyms of two different regimes of political economy—something I feel is relevant to how the political is articulated today.

So you have Crazy Frog—this sort of straightforward symptom of market capitalism of the early 2000s—then you have the figure of Pepe, whose image became the location of an emotionally charged, right-wing, mostly white supremacist political movement. The icons are different, but they share this idea of being symptoms of symptoms.

It's an interesting kind of turn, because in the Pompidou show I have a work titled Evidence of Evidence II (2010), and though formally it is a totally different kind of work, there is some kind of relation to this idea of Pepe and Crazy Frog being symptoms of symptoms.

SBCan you expand on that relation?

HKEvidence of Evidence II is based on an image of a very amateur and damaged painting of geraniums that I found in a Cairo apartment where they were selling all kinds of things. It was in a basket of stuff you could take for free, so it was literally trash. I scanned the object at an extremely high resolution and blew it up to three metres and a half, and in this enlargement, you can see the details of the object.

The painting is composited onto a background gradient made by exposing large-format film to light so it's not a solid, monochromatic colour. There is a natural and very subtle yet perceivable gradient. It produces a very important relationship to the painting which is distinct to using a monochromatic background of solid colour. It suspends it.

I think appropriation is a real and basic constantly ongoing cultural operation...

So this small amateur painting has now become a large suspended image. In one way, it's a forensic exercise because the 'evidence' is blown up. You can inspect it and see how its constituted by painterly gestures like how the brush struck the canvas. You can also see the painting as a historical object in time. It has been damaged—you see the cracks in the paint, the torn bits of canvas, and so on. You can decipher its aesthetics because they're so magnified. So there's that forensic aspect to it.

But then there's also another equally important operation that is taking place in the background, where this painting, which had been discarded and had literally become trash, has been rehabilitated as a work of art. Now it has value, it is being shown in museums, being collected, it has entered this economy of the art world.

This brings up questions that are important to me. What is the artwork? Where is the artwork? How is value produced? What ideologies are latent in forms? And what in forms escapes these ideologies? The painting itself is clearly generic but I've hijacked it.

I'm using the word evidence because it offers different ways of seeing. But then it is evidence of evidence because I'm thinking of the cultural operation as a never-ending chain, where there isn't any moment to rest. We can never find the cause of the symptom. Maybe because there is no one cause, no root; there is no origin and there is no purity.

Maybe because there is no one cause, no root; there is no origin and there is no purity.

Things are always elusive and always one step ahead of us. I might be incorrect, but I feel like this is a more accurate way of approaching culture. If you want to look at it in political terms, it takes us away from the concept of essentialism. It's basically the opposite. It might be old-fashioned, but I'm still involved in this struggle with essentialism. I find it to be a very dangerous instinct, but I recognise it's a real one. It's there and it operates.

I still haven't worked out how essentialism can be generative. Maybe I'm trapped in something, but you know I''m continuously struggling with the concept. I think using the phrases 'evidence of evidence' or 'symptom of a symptom' opens up the possibility of thinking about essentialism in other ways and maybe it offers a way out.

SBThis idea of finding ways out of essentialism comes through in your work with music. You mentioned DOM-TAK-TAK-DOM-TAK was almost algorithmic in how you worked to arrive at the essence of a Shaabi composition.

HKIt's not really the essence of the composition, it is the surface of the form. The algorithmic is of course very important for me. Not as sign of the technological but rather as a basic function of how we're constructed.

The question for me—and it's an old question—is where is the line? Where is the line between what activates us as a conglomeration of chemical reactions and electric nerve impulses and our consciousness of self? Where is that line and how do we navigate it?

This has to do with what is called popular culture and its collectively produced forms, whether a joke, a song, a shop banner, or a way of shaking hands. In orthodox Marxist analysis, this is supposed to ultimately be a reflection of power structures, and though that's an important and generative idea, I don't think it's really sufficient.

Because how are these collectively produced things, whatever they are, able to offer the formal radicalism one finds in a street wedding song or in a secret joke a teenager tells his friend after school?

People make things. And these things are infused with their personal experience, but they're also infused with cultural expectations. They carry ideological messages, but at the same time, there's always this extra gap where something else is happening, which can be confusing, exciting, or both.

You can say that most memes fall into that category. They are symptoms but also active elements with agency as well as (sometimes at least) something slightly beyond our grasp. Maybe this is why I have big issues with both cynicism and certain types of irony, but that's a whole other discussion.

In the case of DOM-TAK-TAK-DOM-TAK and my focus on Shaabi music, there is the algorithmic logic of the piece itself, which was really driven by this much broader question: how is it possible for a cultural form rooted in a patriarchal system to produce something that is much more complex than that system? How can something, for example, be misogynistic yet also formally radical? How is that possible?

But it happens; contradictions exist, and they go way beyond the structures that produce any cultural form.

Shaabi musicians know this music because they have experienced it as a living archive. Culturally, it has a code. So part of DOM-TAK-TAK-DOM-TAK was about touching the code—or what I love calling the cold heart of culture—rather than the personal performance or interpretation of it by making them play without listening to each other. So instead of playing with or against other people, they were relying on the memorised codes they're hearing in their heads.

But it happens; contradictions exist, and they go way beyond the structures that produce any cultural form.

By creating a structure in which the musicians do this, I was hoping to bring the cultural and the generic to the surface. But interestingly enough, because of how I staged this production process and how the work is presented, the result is not musically generic. I find it strangely evocative, because you can hear the genre but actually it's doing something else from what is expected. It's a very strange thing. You're hearing the ghost of the genre but also its latency.

SBIs that where the surplus value of cultural production comes in?

HKThere is actually a new piece in the show titled SURPLUS VALUE (2021), but I shall say no more about it here. To answer your question: yes, but I have no resolution; no answer. I'm always partially very confused, even if I feel driven and engaged.

It's a very important area to stay in, where things are never completely resolved. The concept of surplus value is itself valuable. It motivates how I approach phenomena like the contemporary grotesque, which I find helps to explain in a weird way why and how someone like Donald Trump got to where he is.

I recently did a six-hour seminar with my students about Egyptian popular comedy and the grotesque, and we were discussing through that the possibility of a model of consciousness that is not psychoanalytical—that is not based upon repression, but rather upon looking the other way.

Basically, if we imagine that in a sense, we know everything; that instead of a well of dark unknowns to be conquered—that proto-colonial worldview—we are actually to some degree aware of how we are constructed, what we want, and how to function collectively produced codes. But we just ignore the things that do not fit our specific intentions, ideas, or desires. We, as Barthes put it, basically look the other way.

So it's not that the monster is unleashed and you suddenly discover, for example, that you're a racist. The subject knows very well that they are racist. But they choose to think of themselves as otherwise, as well-intentioned and informed inclusive human beings.

Of course, it doesn't have to be as charged as racism. It can be about anything. In this model, the unknown is not really unknown. It's just ignored. It's just this aspect of the self that you choose not to look at.

If we think about things in those terms, rather than in terms of repression, the whole perspective changes, including our ideas of the political. Of course, these are quite basic ideas at this point. It's not something I've really developed, but it's something I am thinking about and I feel it is related to a lot of my work and to this exhibition and its model of a landscape.

It is not an accident that the title of the show is also the title of two earlier works, neither of which are included in the show, as well as an element from The Agreement, which is in the exhibition.

In this model, the unknown is not really unknown. It's just ignored.

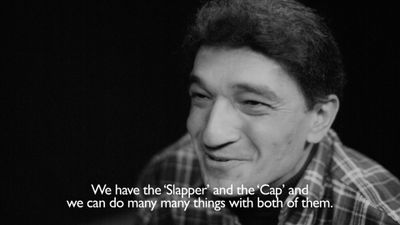

SBWhen you spoke to your students about Egyptian comedy, did you talk to them about The Slapper and the Cap of Invisibility (2015)?

HKYes. I also spoke to the glass artisans at Berlin Glassworks beforehand, which is a glass workshop in Berlin that I work with, about Egyptian comedy. I'm very attracted to the most vulgar of Egyptian comedy, which is totally incorrect, carnivalesque, and demented.

I decided to look at that with them. I did a little lecture about Egyptian comedy, and I showed them examples from the past 50 years, demonstrating how it has steadily become more and more unhinged. I also screened The Slapper and the Cap of Invisibility as an example of how I work with actual existing cultural forms as material. Then we tried to make glass pieces with this logic of craziness, humour,and grotesquery. It was definitively interesting and also kind of fun.

SBHow you describe Egyptian comedy becoming more unhinged somehow speaks to the rise of Donald Trump, and the banners you created for The Keys to the Kingdom. Perhaps the surplus value in culture you mention propels this trajectory: the symptom of the symptom.

HKAbsolutely. However, the character holding the slapper in The Slapper and the Cap of Invisibility represents an older, more classical figure—the naïve fool in the city.

The actor that character was based on, Ismail Yassin, was the pioneer of the style because he was the first Egyptian comedian to push this archetype in cinema to a new extreme—the first to really emphasise certain things, like being gullible and seemingly not too bright by using facial gestures and bodily postures to channel that. The face becomes contorted, the body is exaggerated, and ways of walking become tools of expressing deep emotions.

So here, being afraid is not just being afraid—it's extreme trembling. Everything is stylised for the sake of charge, rather than elegance. It's ultimately a violent performance style that is related to a long tradition of—and I hate the word folk, so let's use another term—'marketplace gestures' and street performance.

What's important for me in this is not some romanticised idea of 'the people', but just the idea of a collective and automated form of cultural production that is 'authorless'. How were specific scales and beats developed? Who wrote them? It blows my mind!

My dream project is to invite look-a-like actors to channel the large pantheon of Egyptian comedians from the past 60 years, from the most insane to the more classical, and to create something with that. I have a whole production process planned. Though I have, over the years, proposed this to many different institutions, nothing has worked so far. It's such a massive project that it's not so easy to find the budget for it.

The Slapper and the Cap of Invisibility was actually made with this bigger dream project in mind, and it chooses these two classical figures because I also wanted to start with something simple and manageable. They're very iconic, their gestures are very well-known. I could work with this as my raw material.

But that also has to do with this understanding of the cultural I brought up earliergain, returning to evidence of evidence, the cultural itself as an instrument to be performed, rather than something to be spoken about. The Slapper and the Cap of Invisibility is not about Egyptian cinema or comedy: it's partially of it, but it is also something else.

Film culture itself is the instrument, the performance of these characters and even the characters themselves—all of these are instruments. Just as the first blurb I wrote for tabla dubb (2016) says, I'm interested treating musical culture itself as the instrument.

SBThat's what you said about Club Gamelan, that you are looking at this musical form as an instrument, which is why you don't look at your engagement as exoticisation. But is there a difference in how you've treated Shaabi music, which is rooted to your context as an Egyptian, in relation to gamelan and hip hop?

HKNo, I wouldn't. My references have always been multiple both chronologically and geographically. I grew up questioning fixed identities and I have no guilt about my position, as one of the whispered sentences of Transmission (2002), another rarely seen work included in this show, puts it: 'to have equal rights on the street like any other pickpocket'.

This attitude came from being aware of systems of power. The advantage of growing up in places where authoritarianism is explicit, is a deep and sensorial understanding of power.

In 2005, when I produced DOM-TAK-TAK-DOM-TAK, I thought it proposed a sort of home-made organic algorithmicism. By 2019, when I wanted to do something with The Infinite Hip-Hop Song, I was interested in using the power and the logic of machine-driven learning as a compositional and production tool, rather than as a form of reading.

What's important for me in this is not some romanticised idea of 'the people', but just the idea of a collective and automated form of cultural production that is 'authorless'.

A lot of what happens within the field of machine learning is that these tools are used to read what exists, and through that reading to amass, categorise, and analyse data, which is then used to create an algorithmic system that produces something—a replica that resonates or sounds like what already exists. Let's scan all Beatles songs and make a Beatles song—the future as a way of producing the past!

My interest was in developing something different: how could I create an algorithmic structure that can be used as a tool, while still maintaining my position as the author, and refusing to hide that structural fact? I feel this can also have political ramifications, as without authorship there is no real responsibility. But is it possible to do that while also losing control? How could I produce a form that speaks a language akin but not completely coincidental to the genre? How can this be meaningful and yet also speak on other levels?

What I was interested in finding while working with the rappers in the studio, for example, was ways of producing performances that were potent and charged: moments of density where the accumulated power of the collective genre articulates something authored. —[O]

2 Hassan Khan, video interview, URSSS, June 2015.