Nell: 'I'm always thinking about how a painting might sound'

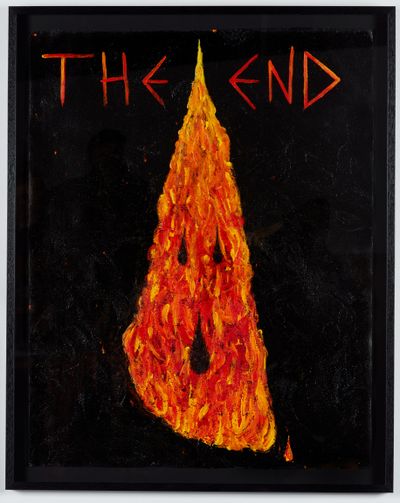

Nell. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Ryan Brabazon.

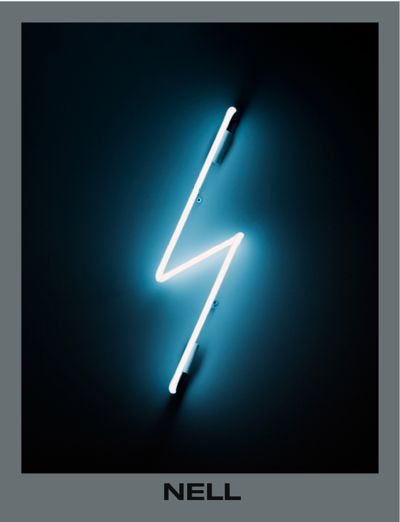

Nell. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Ryan Brabazon.

Sydney-based artist Nell has a capacious practice, working deftly across sculpture, painting, sound, assemblage, performance, and public art, producing work that is both accessible yet complex.

Her repertoire of symbology incorporates language, crosses, smiley faces, and orb shapes combined with a deep interest in music and lyrics, feminism and spirituality, life and death. These polarities are seamlessly integrated in canvases, neons, and assemblages often emblazoned with fonts and pithy aphorisms. In 2011, Nell audaciously restaged AC/DC's song 'It's A Long Way To the Top (If You Wanna Rock 'n' Roll)', playing bass herself in an all-girl rock band with bag pipes.

Nell trained in painting at the Sydney College of the Arts with Lindy Lee, performance and installation at UCLA with Joan Jonas and John Baldessari, and with Annette Messager at the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts, Paris. These foundations have led to a practice that is open and curious, flexible and encompassing. She has exhibited across Australia and New Zealand and participated in exhibitions in Amsterdam, Rome, Paris, Beijing, and Los Angeles.

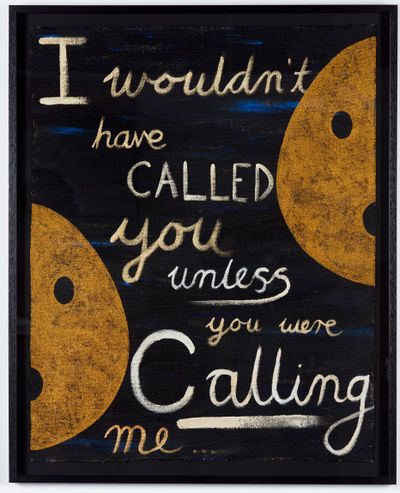

Relishing language and lyrics, Nell deploys intriguing titles such as Hometown Girl Has Wet Dream for her solo exhibition in her hometown, Maitland Regional Art Gallery in 2012, or I wouldn't have CALLED you unless you were calling me (2019) whereby text is emblazoned across the canvas in a manner that recalls the work of New Zealand's Colin McCahon, yet imbued with pathos and ghostly faces.

Known as a rock chick who loves meditation, Zen, and AC/DC, Nell's witty repartee appears in the stone sculpture Happy Ending (2017), although there are overlayed references to death and burial, relationships, and loss. It is these profound nuances that are at the core of her practice.

On the eve of her new exhibition, I SAW the LIGHT at STATION in Melbourne (8 May–5 June 2021), Nell was in conversation with curator Natalie King, following on from the publication of their Mini Monograph last year with Thames & Hudson.

This conversation was conducted via email and phone while Nell was moving into a new studio at the Powerhouse Museum and Natalie King was ensconced in her home office in Melbourne on Naarm Country. They discuss sunshine in Brisbane, the companionship of music and lightning bolts, as well as the influence of Hank Williams and Kim Gordon.

NKYou were born in Maitland, in rural New South Wales. What inspired you to become an artist? Was there an epiphany?

NYes, I grew up in Maitland, in the same house from when I was born until I left for Sydney to go to art school. My parents were both public servants. I craved cultural stimulation and there wasn't much to be found.

Without any encouragement or role model, I drew and painted, made children's books, tie-dyed clothes, wrote poetry, and played guitar. But I couldn't wait to leave, as I knew the whole world was waiting for me!

If there was an epiphany it was AM and FM radio. Music was my portal to that waiting world. In retrospect, there is no doubt that the absence of the cultural life I wished for fostered a rich imaginative life and a deep resourcefulness within me to make things regardless of the circumstances. And yet, growing up in Maitland seeped into my art practice—the music from the radio, blow flies, the aesthetics of Sunday school, and even cricket.

NKCan you discuss how music has been central to your practice?

NArt and music just make more sense to me than anything else! For me, music and art are simultaneously essential and mysterious.

Music is a constant studio companion. I like to have a 'soundtrack' for a body of artwork or a show. There is that oft-quoted neuroscientific theory that the neurons that fire together, wire together. When I arrive at the studio and put on a particular piece of music, it allows me to seamlessly return to that 'making space' day after day.

If there was an epiphany it was AM and FM radio. Music was my portal to that waiting world.

For many years afterwards, when I revisit some of my artworks, I can hear the music I was listening to at the time of making.

I'm always thinking about how a painting might sound or how installing a suite of works in a space is like the sequence of songs on an album. Or how sculptures sit together like band members on a stage—each separate but offering something to a unified experience.

NKHow do words, phrases, poems, aphorisms, and lyrics infiltrate your work whereby you have developed a lexicon of placing language alongside visuals?

NI love how a throw-away line from a song in popular culture can be utterly profound and resonate on multiple levels. For me, AC/DC's 'Who Made Who' is the ultimate Zen koan!

Using words and text in my works, whether they come from songs or not, is a straightforward way of engaging an audience, because you simply can't unread words once you have read them. The shapes, scales, and fonts of the letters and words all contribute to their meaning, too. Often, the titles of my works are responses to the text in them, like the call and response in music.

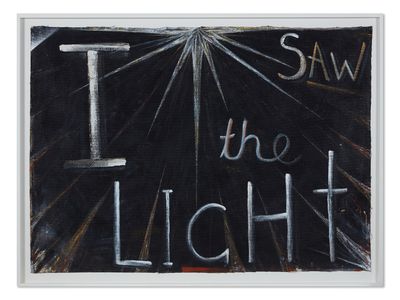

NKYour new exhibition I SAW the LIGHT is partly derived from a country song by Hank Williams. I am keen to discuss the associative range within the title from illumination, religion, and spirituality to your interest in meditation and Buddhism?

NAs you can guess, I am a long-time, passionate fan of rock 'n roll. Recently, however, I have become obsessed with the origins of country music in America and Hank Williams in particular.

As a friend reminded me, there is a reason Leonard Cohen sings that Hank Williams is 'a hundred floors above me in the Tower of Song'. 'I Saw the Light' isn't just a country song, it's a folk song and a gospel song of redemption for ordinary people. Likewise, I'm never looking for grand religious things or moments; rather, I'm interested in the spiritual in the everyday encounters and stuff of life. And it's everywhere!

Moving back and forth between light and dark is at the core of existence—birth and death, day and night, sounds arising from and returning to silence, and on and on it goes. The magic of what is between dark and light or any absolutes is the present moment. All I try and do is open myself to the flow of life and make work from that place.

A change had been quietly gestating within me for a long time, and in 2020 I released myself from a situation I was deeply unhappy with. Williams' 'I Saw the Light' became my anthem for that internal shift, and I listened to the song a ridiculous number of times. Hence, I made a painting with those words, which is also the title of my upcoming exhibition in Melbourne.

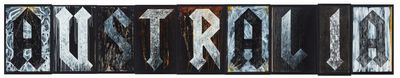

NKTell me about the other painting in this exhibition—AUSTRALIA (2020), which is in the AC/DC font?

NI hardly know where to start when talking about AC/DC or this painting! First, I love AC/DC's music and their concerts are incredible. I love how dedicated their fans are, I love the font, the paraphernalia and the entire phenomenon that is AC/DC.

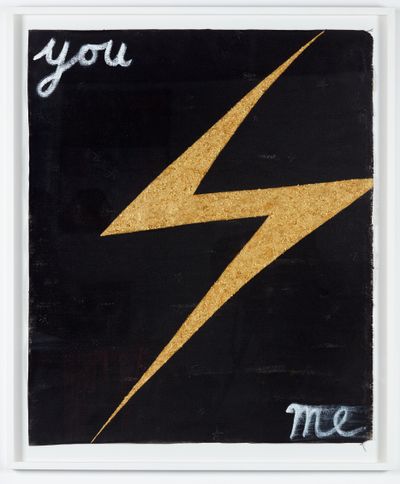

I've worked on an AC/DC music video. I've used all kinds of AC/DC merchandise in my work, and I've also adopted the lightning bolt as symbol for in-between places, which riffs on the colloquial use of word AC/DC as a synonym for bisexuality. A neon lightning bolt appears on the cover of the book we did together.

About ten years ago, I put together an all-girl band and restaged their famous 1976 video, 'It's a Long Way to the Top (If You Wanna Rock 'n' Roll)' using the original bagpipers. You can see it on YouTube.

Anyway, this painting came about because as I was researching country music, I started thinking about the terroir of music; about how climate, soil, and geography affects the sounds that come out of a specific place.

This was all in my mind as I spied an AC/DC T-shirt in my studio with the word AUSTRALIA emblazoned in the AC/DC font. I realised the band uses their font for a country's name as if they belonged there, such as WARSAW, POLAND, or AUCKLAND, NEW ZEALAND, and somehow it always looks right.

I find it fascinating that a song or music that arises from a specific set of conditions can have such universal appeal in completely different times and localities.

And then, I was thinking about what country actually means in the Australian context of Indigenous Australians' special relationship with Country. In what has become an important and wonderful custom in Australia, every time there is a public gathering where people meet, the Country one is on and the Indigenous people of that Country are respectfully acknowledged.

There are hundreds of Indigenous Countries in Australia. I'm on Gadigal land of Eora Nation right now. Maitland, where I grew up, is on Wonnarua Country.

When the British arrived and invaded, they couldn't understand Country. All they could see was 'landscape'—land to be controlled, tamed, and styled in the fashion they knew. From that time, right up until today, the genre of landscape painting in Australia is still seen through a European gaze.

Within this framework, my new AUSTRALIA painting is my offering to this history of landscape painting without a horizon line or tree in sight! At nearly seven metres long, the painting is in a traditional landscape format where the viewer has to stand back from the work to see it in its totality. From that position, the painting is clearly black and white, but the closer you get, the more colours you see.

NKLast year we worked on a Mini Monograph with Thames & Hudson and commissioned Robert Forster from The Go-Betweens to write a parallel text on your work. Robert reflects on 'the overwhelming beauty and ecstatic shimmer' of Unlimited Radiance (2001).

Can we discuss how you cycle from incandescence in your work to more austere symbols of crosses, religious symbols, sentences, and slogans?

NIt's interesting we have been talking about the relationship between environment and music, because The Go-Betweens are regularly described as having a 'sun-drenched' sound.

After struggling in London for many years, The Go-Betweens returned to Australia and made the most beautiful album—16 Lovers Lane is soaked in sunlight. In it, I can hear Sydney's warmth. Robert is from Brisbane where the sun is always shining, so it's no wonder he connected with Unlimited Radiance.

As to how my practice cycles around those visual languages, it is, as you say, a cycle. I've been making art for over 25 years, and it feels like a journey of trial and error of working with pre-existing visual languages, jettisoning what doesn't work, and collecting what does to be reconfigured and recontextualised in the future.

It's a limitless cycle—there will always be new ways to say old things and old ways to say new things. The Mini Monograph assembles different aspects of my practice while drawing out confluences, such as spirit sculptures, numerology, language, crosses, and smiley faces in a repertoire that I constantly return to.

NKYou have a material range from sculpture, found objects, paintings, and neons. Can you elaborate on this dexterity of media and what kinds of material are important to you?

NAll materials have energy. And meaning. That's why having a studio is so important to me, as it's a dedicated space to commune with materials.

I go to great lengths to research and understand materials and their place both in life and art history. Materials are like good friends, where the relationship deepens over time. In particular, I find there is something special about the combination of the handmade and found objects from the natural world.

Because my practice is so materially diverse, it has probably been challenging for audiences to see the consistent threads running through it.

Regardless of material outcome, my work is always exploring thresholds of binary opposites, such as the ancient and contemporary, individual and communal, feminine and masculine, sacred and profane, and so on. I'm either trying to amplify the tensions or marry the differences between these binary positions.

NKYou have been working seamlessly between museum exhibitions and public art, probably because your work has strong visual resonances and is accessible. Eveleigh Treehouse from 2019 communes with nature, site, and history, and comprises two treehouses on elongated legs that are conjoined by low walkways sitting gently across Eveleigh Green.

Over 400 volunteer members of the local community in Eveleigh, New South Wales, forged individual metal gum leaves with personal inscriptions that your transformed into a hospitable cave with curved, arched entrances resembling a cheeky face. Can you discuss how you consulted with communities and the anthropomorphic aspects of this work?

NI started with my personal connection to Eveleigh Railways, as my great-grandfather worked in Bay 4 as a boilermaker during the Great Depression. The pods of Eveleigh Treehouse were made at Eveleigh Works in Bays 1 and 2—the oldest continuing Victorian blacksmith's workshop in the world.

Eveleigh Treehouse was handmade using Victorian-era methods and tools, just a few hundred metres from where the tree houses now live. We did a callout to the general public to forge gum leaves, which could be personalised with initials or an inscription. It was so cool to have people from all walks of life come together for a shared purpose. Eveleigh Treehouse was made by the community and belongs to the community.

Moving back and forth between light and dark is at the core of existence—birth and death, day and night, sounds arising from and returning to silence, and on and on it goes.

I borrowed the personality and face of the tree house from the façade of the individual work bays at Eveleigh and Carriageworks. The tree houses are on legs, so it looks like one of the individual work bays got up and walked over to Eveleigh Green and has become slowly entangled with the native gum trees over time, or like the industrial architecture and the gum trees made love so that the Eveleigh Treehouses are their love children! There's also a beautiful Australiana feel to it.

I like to describe Eveleigh Treehouse as a secular gum leaf temple. I have a great belief in the ability of art to elevate our experience of daily life and to create environments that uplift and connect us.

NKMany of your sculptures resemble ghostly faces or childlike grimaces, maybe even cartoon characters. Do you see them as a tribe or family?

NI am really passionate about communicating directly and clearly. I feel like my works with simple faces on them do this.

When I make a face on a work, it instantly has a spirit and a character. And when displayed collectively, these characters are very much like an extended family. My experience of making these kinds of works is joyous and full of childlike wonder.

I especially like putting smiley faces on things that you wouldn't at first associate with happiness, like a storm cloud, a gravestone, or a poo, because you can no longer read the object as negative or sad—the smile is always stronger. It doesn't matter what your cultural background is or how old you are, you know what a smile or a tear coming out of an eye means.

NKYou are currently included in the National Gallery of Australia's tome exhibition Know My Name (14 November 2020–9 May 2021) that reinstates the work of women artists in a call to action.

Could we return to our joint commitment to feminism and discuss the memoir of Sonic Youth's Kim Gordon, Girl in a Band (2015), and how, for both of you, your work and life is full of haunting insights, relationships, music and art, marriage and independence, laughter and love?

NFeminism is a human rights issue. Full stop. I have huge admiration for people who are calling out discrimination and are actively involved in consciously rebuilding organisations.

Equally inspiring and encouraging are women who do their thing and are visible in their field. I saw Sonic Youth play the day I turned 18, and seeing Kim Gordon up on stage was a powerful experience. She has been someone I grew up with from afar, both in life and music.

Her memoir traces her journey from girl in a band to woman of the world. Powerful and creative women rock my world—you, Kim Gordon, Dolly Parton, Amy Taylor from Amyl and the Sniffers, Sister Rosetta Tharpe, and my wife! —[O]