MetaObjects: Towards a Theory of Studio Practice

Ashley Lee Wong and Andrew Crowe. Courtesy MetaObjects.

Ashley Lee Wong and Andrew Crowe. Courtesy MetaObjects.

MetaObjects is often credited in parentheses, receiving attributions for technical support, digital development, and videography. Yet technology is not an end in itself for this Hong Kong-based studio; it is a means to foster collectivity and theorise other 'modes of making'.1

Somewhere between production house, curatorial office, and technology consultancy, MetaObjects was founded in 2017 by curator and researcher Ashley Lee Wong and software engineer and technologist Andrew Crowe. It has since worked with artists and institutions to realise projects through various specialised processes, from virtual reality to blockchain.

In a sustained relationship with Lu Yang, the studio has been involved in rigging 3D models, mapping live motion capture data to 3D avatars, and developing the performance Electromagnetic Brainology Live for different motion-tracking systems—from consumer-grade HTC Vive to the more robust OptiTrack—for Powerlong Art Centre's inaugural exhibition in Hangzhou, Nine Tomorrows (4 May–4 August 2018), and as part of the programme for RAM HIGHLIGHT 2018: Is It My Body? at Shanghai's Rockbund Art Museum (29 September–4 October 2018).

For the installation Dance Dance Lu Yang Revolution at the 12th Shanghai Biennale (10 November 2018–10 March 2019), the studio collaborated with the artist on a game design inspired by Konami's popular eponymous Dance Dance Revolution (DDR), modifying a dance platform arcade cabinet so players could 'dance' Lu Yang's version on it.

MetaObjects also worked on Lu Yang's first live-streamed performance, Delusional World (11 November 2020), presented by ACMI, Asia TOPA, Arts Centre Melbourne, and Exhibitionist. As Wong explains, 'each performance is taken as an opportunity to upgrade the performance in increasing complexity. Lu Yang provides the assets and we program the interaction and systems.'

Other recent projects include the creation of three 3D printed mannequins for the sculptural work Falling Carefully (2020) by performance artist Isaac Chong Wai, included in Next Act: Contemporary Art from Hong Kong at Asia Society Hong Kong (8 May 2020–14 March 2021), as well as a 360 virtual gallery tour of the group exhibition My Body Holds Its Shape at Tai Kwun Contemporary (25 May–20 September 2020).

MetaObjects' collaboration on a blockchain project with artist and composer Samson Young, called Ensembl, will be presented at the DAOWO (Decentralised Autonomous Organisation With Others) Sessions (25 February 2021) supported by the Goethe-Institut London, Furtherfield/DECAL, and Serpentine Galleries. The M+ museum of visual culture has also contracted MetaObjects to advise on curatorial content for the large-scale LED media façade of its new Herzog & de Meuron-designed building.

All of this might leave the impression that MetaObjects' work is defined by technical expertise; but, their contributions are also conceptual, and theory is part of their practice.

Wong recently completed her doctoral studies at City University of Hong Kong and in her theorisation of the studio's practice, makes reference to physicist and theorist Karen Barad's challenge to the common notion of objectivity as a position outside.2 Wong conceives of collaborating through 3D printing as a 'transindividuation process' in which 'taking care of the object transforms both subject and object.'3

Combining Crowe's background in programming with Wong's training as an artist and experience researching creative economies, MetaObjects is, as Wong describes, 'a testing grounds to understand the social and material potentials of an environment . . . by making propositions that open up to new possibilities.'

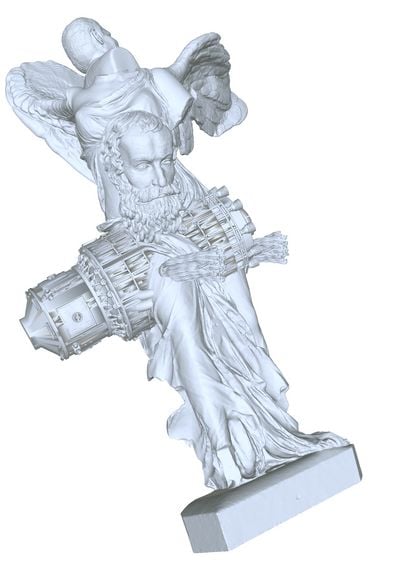

Artist Samson Young describes MetaObjects as 'resourceful'—an apt description that aligns with MetaObjects' own thinking about its approach as 'attuned to the "lure of the possible"'.4 Young's monumental 3D print for Palazzo Gundane (homage to the myth-maker who fell to earth) (2017), the M+ commission that represented Hong Kong at the 57th Venice Biennale, was the studio's first major project.

Before starting MetaObjects, Wong was involved in co-founding DOXA, a collective of artists, theorists, and designers, and Crowe regularly assisted artist friends with video interviews, photography, and web development. During this period, the two lived in London, where they started small home-printing jobs through 3D Hubs, a peer-to-peer online platform for 3D printing. Arriving in Hong Kong in 2017, they found the platform less popular, with low-cost services easy to access across the mainland boundary in Shenzhen.

The opportunity to continue cultivating collectivity by redistributing resources returned after the Venice Biennale project, when Young acquired a Builder Extreme 2000 for large-format 3D printing. MetaObjects not only maintained the machine, made custom adjustments, and helped explore its creative capacities; they also facilitated its sharing. The printer became an agent of community-building.

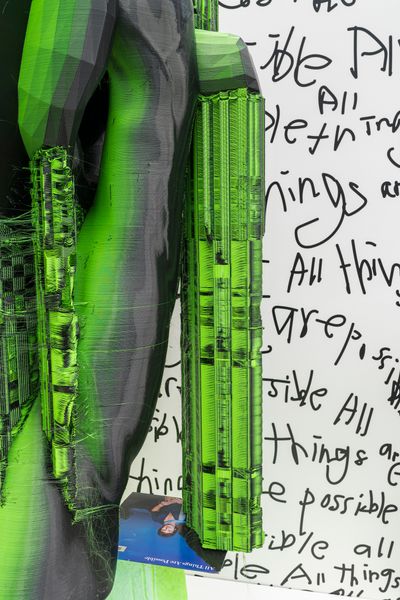

In further collaborations with Young, MetaObjects worked with the Builder Extreme 2000 on large-scale wall-mounted sculptures for Possible Music #1 (2018)—an installation included in the group exhibition One Hand Clapping at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York (4 May–21 October 2018)—and a 'playable garden' comprised of large 3D prints at the K11 Musea in Hong Kong for Big Big Company (Mini-Golf) (2019). Later, they planned projects for Young's printer with other artists like Chong.

While there are other studios in Hong Kong working with the cultural sector, they define themselves as using art and technology to create digital experiences; MetaObjects considers itself a studio for 'artist-led' technology-based inquiry. Similar post-critical studios like the New York-based Foreign Objects and The Hague-based The Rodina produce their own art; MetaObjects currently does not.

'I think of the studio as an art project, but I don't intend it to be explicit. I just want to demonstrate that we can do things that are not necessarily following the typical paths of the creative agency,' Wong explained during our conversation at their studio in Cheung Sha Wan. 'It's about finding sustainable economies to support artists knowing that common challenges are access to technology and technical skills to make work.'

EVBYou've worked with artists, designers, and institutions on a variety of different projects that involve virtual reality, augmented reality, 3D printing, motion capture, audiovisual production, software, and web development. Could you talk about how you started your work and developed the attitude of openness that you bring into each collaboration?

ACI come from a software engineering and web application development background, ranging from finance to social media startups to creative agencies.

I've always been a tech enthusiast, so we were early adopters of a 3D printer and VR. I wanted to do some more fun creative stuff as a career, instead of just staying as a web application programmer.

AWI was working with Sedition, the London-based online platform for selling and trading art in digital format, where I met a lot of artists, partners, and institutions, and became interested in building on those networks in ways that were not just about selling digital art but supporting artists and building more meaningful relationships through artistic production.

Andy also worked with some of his artist friends in London, photographing their events and doing their websites. At that time, it was purely a hobby. We just wanted to help. Then we also did some 3D printing. That's when we bought the FormLabs Form 1+ and started to run it as a service on 3D Hubs.

We don't have a goal, we just put ourselves and our propositions out there to support and enable others.

ACAnyone who owned a 3D printer could register it with 3D Hubs and people could pay you to run prints for them. Ours was a more expensive resin-based printer. There were certain pitfalls with it, but you get nice quality, so we immediately got a lot of work.

AWThat was around 2014 or 2015 when there was a lot of hype around 3D printing. Now 3D Hubs has changed their model to just support industrial-size on-demand manufacturing. They don't do peer-to-peer anymore.

Costs have come down so much that a lot of artists have their own 3D printer. I wrote a blog post about our 3D print experience just after we moved here and put it on Medium. We almost made back all the money we spent on the printer by doing these small jobs on 3D Hubs.

ACPrinting for other people, you get so many interesting jobs. Everything from detailed figurine board game pieces to fashion accessories, like intricate shoe buckles or design prototypes.

AWWe took the projects as a learning process and we do the same now. The artists we work with come up with so many different things. It might not be something we have worked with before, but we take it as an opportunity to learn with the artist.

We moved to Hong Kong because I was offered a PhD fellowship at City University of Hong Kong. But also it was a chance to start our own projects, which we always wanted to do, after leaving full-time jobs in London. MetaObjects also became a means to test out ideas as part of the research I was doing.

EVBYou've called your approach 'artist-led'. Can you talk about this in relation to the work you did on the Venice Biennale project with Samson Young?

ACSamson does his own 3D modelling, so for the Venice Biennale print, he combined a series of objects, including the ancient Greek sculpture of the Nike of Samothrace, busts of Greek philosopher Pythagoras and President Ronald Reagan, and a space station, which we then printed as a single form. Cosmo Wenman applied the texture to the piece and helped to print it.

Most 3D models, especially 3D scans and freely available paid assets, are designed for on-screen 3D rendering, so they're not solid. They're just the equivalent of a hollow paper shell with nothing inside them. We were brought in to make the design printable and to apply special effects.

AWInitially, Samson wanted the print as a standing figure, but we were concerned the wings of the Nike of Samothrace would be too heavy and it would need internal metal supports. That posed a challenge, so Samson started to rethink it with us and together we came up with the idea that it could be lying down.

Samson thought it could symbolise a fallen empire, but then he asked us to figure out how to melt the wings and cut the statue so that it looks like it is embedded in the ground beneath it. Andy used the liquid simulator in Blender's physics effects for that. The technical limitations start to inform the creative process and the form of the work itself.

ACIt all happened through conversation. The same issue came up for Isaac Chong Wai in Falling Carefully (2020), a much later project we did for the exhibition Next Act: Contemporary Art from Hong Kong at Asia Society.

He wanted to make the figures life-size, but they would have been too heavy to support themselves, so we looked into how much it would cost to create an internal metal structure for them. He asked if it would work if he just made them smaller so that they'd be strong enough to be free-standing.

EVBAfter the Venice Biennale project, Samson Young bought a Builder Extreme 2000, an FDM printer that you then worked with for the wall-mounted sculptures in his installation Possible Music #1, presented at the Guggenheim. That's also the printer that you worked with for Isaac Chong Wai's Falling Carefully.

So, in addition to working with Young on the actual production of some of his objects, you've worked with him on his community-building efforts by facilitating the sharing of the printer that he purchased.

AWExactly. We opened that printer up for other artists and then shared the revenue with Samson. We did Isaac's print and some work for another young Hong Kong artist, Vvzela Kook, as well as some City U PhD students.

For Samson, having the printer allows him to work more closely with the medium and trial-and-error much quicker. For example, it has two feeds, so you can have two different colours running through it, so he started to play around with creating marbling and gradient effects.

EVBHe had a large standing hybrid figure—a cross between a drum set and a humanoid being—that used a green-black colour gradient in the exhibition Instrumentation at the Hong Kong Visual Arts Centre.

AWYes, and Big Big Company (Mini Golf) (2019) at K11 Musea, which we worked on, is multicoloured and uses gradients.

He also uses it to create frames for his sound drawings. They have a marbled effect. The K11 project was huge; it took months. He saved money on production and the shipping that he would have had to pay for if he had it done commercially.

It is important to Samson that he supports other artists. He's done this, for example, in his work with Contemporary Musiking, which he founded in Hong Kong in 2007 to promote cross-disciplinary practices in sound.

Samson may not have been comfortable managing the printer on his own. He knows the basics but if something goes wrong, like something gets stuck or one of the nozzles need replacing, then we help with that. Andy made some modifications to the printer to make it easier to manage.

ACThe printers have sensors to detect when filament runs out, but all they can detect is when the last of the filament gets pulled through a very simple switch sensor.

I think of MetaObjects as an experiment. It is constantly renegotiating what's happening in the world around us and the given possibilities in a time and space, especially now with the coronavirus.

There are so many other things that can go wrong: sometimes the filament gets clogged or snapped and the sensor can't detect it because there is still filament in the switch. In these scenarios, the print is typically ruined.

I use an Arduino with rotation sensors to check the reels are still turning. If they stop, it uses a relay to activate the printer's filament sensor and it pauses. I had read articles about how people had done similar things, so I incorporated those ideas into the physical layout of Samson's printer.

EVBAnother important collaboration has been with Lu Yang. You started working with her in 2018. Like the 3D printing work with Young, the projects with Lu Yang also developed over time in response to the systems and devices you were using in your work with motion capture, game design, and live-streamed performances.

AWLu Yang takes each performance as an opportunity to develop a project further. For the first one, Electromagnetic Brainology, we didn't have a budget, so we worked with very affordable consumer technology, HTC Vive Trackers.

ACThis is something people have been doing, using software developed by another company, IKinema.

AWEvery time it's performed, it's slightly different. The next time we did it was in Hangzhou at the Powerlong Art Centre. We worked with the VirREAL Center for Art and Technology at the Hangzhou China Academy of Art where Lu Yang studied.

Curator Yao Dajuin runs the lab there and had an OptiTrack system, which is much more expensive and harder to access. We spent a week there using the system to upgrade the performance.

After that, we did it again at Rockbund Art Museum. We learned that Chronus Art Center has OptiTrack and we had participated in a workshop with them, so Rockbund rented the OptiTrack from Chronus for the performance. They were able to have three dancers instead of one with a light-up stage, more characters, more scene changes, and more visual effects.

EVBSo, each time you worked on the performance, it got more complex, not only in terms of the technical equipment, but in terms of the concept and the network of social relationships it involved.

AWYeah, it is an ever-expanding universe. We didn't do the performance for a full year after that, but Lu Yang wanted a Dance Dance Revolution arcade game

ACLu Yang had a lot of old arcade cabinets, mainly just to play videos on their screens for her installations, but she had a second-hand DDR cabinet she wanted to make into a working DDR game, so she got us to create the game for her in the game engine Unity and we travelled to Shanghai to hack the arcade cabinet and play our software on it, still using the dance pad as a controller.

The DDR pad is just a bunch of microswitches under Perspex panels, so I brought a cheap USB joypad along, soldered the connectors of these microswitches onto the pads of the joypad, and then the DDR pad could be plugged into the USB port on a PC and it registered button presses on the controller when you stamped on the pad.

The arcade cabinet was built around an HDMI monitor, so we just brought our own PC, put it behind the cabinet, and plugged the HDMI into the monitor connection.

AWShe's now incorporated that DDR game into her ten-level game, The Great Adventure of the Material World (2019), first presented in her solo show, The Game World of the Material World Knight at CC Foundation in Shanghai, so that was the next game project. She wants to put it on Steam, a game app store.

You can't die in the game: it is very much an artwork. It is about navigating her world. You can fight the demons that are in the world and there are certain narratives around her universe, the characters, and objects that you encounter, but technically, you cannot die. Though you may have to fight or shoot, in the end, you are fighting yourself.

ACThere are games sold on Steam like that. They've been called 'walking simulators'—you're just exploring a world. Irish artist and game developer David OReilly's work Everything (2017) is like that. It has British writer Alan Watts's metaphysical narration of the existence of life in the universe from micro to macro.

EVBMetaObjects has been contracted by M+ for two projects and is working with Samson Young on a blockchain initiative. Can you speak briefly about M+ and blockchain?

AWM+ contracted us to assist in advising on the curatorial content and consulting on technical implementation, delivery, and workflows for the museum's large-scale LED media façade, and we're also working on a new multi-sensory installation within the museum.

We're always experimenting with what we are and what we could be.

As you said, we're also working with blockchain. Blockchain is a computational system that allows transaction information to be recorded and distributed across many computers, and the ledger's verifiable without going through a centralised third party.

There's been a lot of research on the potential to apply it to cooperative work and artistic practices by financialising a studio's governance and activities, like in the speculative art projects of Ed Fornieles and Jonas Lund.

We're collaborating with Samson on the DAOWO Sessions supported by Serpentine Galleries and the Goethe-Institut.

Samson wants to use blockchain technology to create a platform for copyright and mechanical rights in the context of musical compositions. Interdisciplinary musical compositions often involve things like improvisation in response to indeterminate notation, and he thinks this deserves more consideration when it comes to the question of value-sharing among composers and musicians.

So, basically the project is to produce an app called Ensembl that could help automate the processes of negotiation and distribution, making them more transparent. We're having conversations with him about both the technical and conceptual aspects and will participate in an online event about it for the DAOWO Sessions in February.

EVBIn what computer scientists call 'metaobject protocol', the metaobject implements itself and other objects in processes that make constant reference to the conventions within which it is operating.

I see your work with the studio as similarly self-referential in the sense that you use your studio practice to very deliberately reflect on the processes and conditions within which you are working.

AWI think some people think we just work with artists and make their work for them [laughs].

I think of MetaObjects as an experiment. It is constantly renegotiating what's happening in the world around us and the given possibilities in a time and space, especially now with the coronavirus.

I've heard people say it's quite unusual to have a studio like ours that specialises in working with art and artists, because it doesn't make money. A lot of agencies will only work with commercial brands because they've got big budgets.

So, people ask us, how do you sustain it? It's a balancing act. We're always experimenting with what we are and what we could be. We don't have a goal, we just put ourselves and our propositions out there to support and enable others.—[O]

1 Ashley Lee Wong, Emergent Economies of Art & Technology: Modes of Making, Circulating and Organizing in the Contemporary Condition. PhD Dissertation. School of Creative Media, The City University of Hong Kong (December 2020): p.9. Wong cites Giorgio Agamben's use of the term 'modes' in The Coming Community (1990).

2 Karen Barad, Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning, (Duke University Press: Durham, NC, 2007), p.185.

3 Wong, Emergent Economies of Art & Technology, p.339. This term is derived from Bernard Stiegler via Gilbert Simondon.

4 The phrase 'lure of the possible' comes from philosopher Alfred Whitehead. Wong, Emergent Economies of Art & Technology, p.330.