Stanley Whitney on Dream Time and Going Where the Work Takes Him

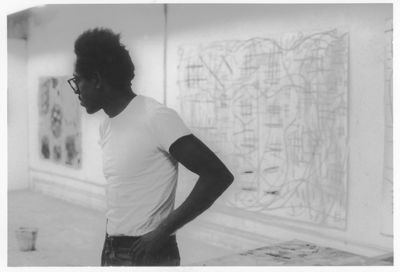

Stanley Whitney, 2023. Photo: © Aundre Larrow.

Stanley Whitney, 2023. Photo: © Aundre Larrow.

For many artists, accolades and praise come late, if at all. Stanley Whitney stayed true to his practice even when no one was looking, leading to a reputation as one of the most important American abstract painters of his generation.

With the exhibition Stanley Whitney: How High the Moon—presented first at Buffalo AKG Art Museum in New York (9 February–26 May 2024), and tapped to tour to Minneapolis' Walker Art Center and the ICA/Boston—the Philadelphia-born painter receives his first full-career retrospective.

The exhibition is testament to Whitney's consistency and artistic daring, even through times when very few people were interested in what he was doing. Over 50 years of experimentation with the rhythm and meaning of colour have resulted in works that pull viewers into complex spatial landscapes of human experience.

Consisting of close to 200 works, including never-seen paintings, sketchbooks, and drawings, presented chronologically from the 1970s to recent years, How High the Moon opens with early works that see Whitney experimenting with paint, composition, and subject. Paintings like Untitled (1979), with its globular shapes and pastel colours, show the artist grappling with figurative elements of foreground and background, object and field, offering glimpses of the artist's journey towards the large, grid-form paintings that anchor the show.

While attending an art programme over the summer of 1968 at Skidmore College in Saratoga Springs, New York, Whitney became friendly with his teacher Philip Guston, who encouraged him to move to New York.

In 1968, while living in Brooklyn, Whitney immersed himself in the downtown art scene, visiting galleries and mixing in the same circles as artists such as a Robert Rauschenberg, Donald Judd, and Frank Stella, among others. However, he felt he didn't fit in. He wasn't particularly interested in their approaches to painting, nor in the figurative work that many Black artists were exploring at the time.

Whitney enrolled at Yale and completed an MFA in 1972, focusing his time there on experimentation with materials, and citing painters Henri Matisse, Mark Rothko, Ed Clark, and Jack Whitten as influences. He references the latter two in relation to the work Untitled (1978), which can be seen in the opening stages of the Buffalo AKG retrospective. The large acrylic painting was made using a mop—an enquiry into how to use paint and colour to achieve the desired effects of density and weight.

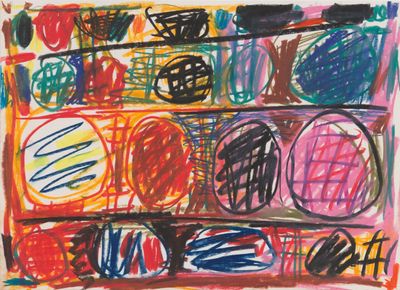

In Untitled (1991), Whitney's free-floating circular shapes are situated between horizontal lines that give the colours a structure in which to be contemplated. The grid leads the viewer to focus on the colours themselves, along with their relationship to each other, calling forward the artist's lifelong concern for rhythm, as well as call and response.

Whitney further solidified his grid-like paintings in the early 1990s, at a time when interest in abstract painting was at low point. Five years in Rome from 1992 with his wife, artist Marina Adams, proved to be a turning point for the artist, with the Italian architecture steering him towards the idea of the unification of space and colour.

In the early 2000s, Whitney completely moved away from the circular form and started to create the works he is today most known for. Large, square-format, gridded canvasses show blocks of vibrant colours stacked upon each other, suggestive of Roman architectural forms. Freed in this approach to focus on colour association and process, works such as Here and There (2001) exemplify Whitney's exploration of how colour and paint work through rhythm and association.

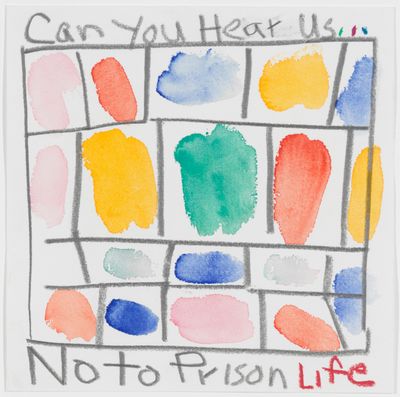

Despite having abandoned figurative art early in his career, with a view to slip the social and political strictures of representation, Whitney's most recent works have taken on political undertones through his use of title. His 'No to Prison Life' series (2016–ongoing)—colourful improvisatory crayon drawings that feature free-flowing lines within squares—demonstrate a concern for Black experiences in the U.S.

In the following interview, Whitney discusses his formative years as an artist and reflects on achieving late-career success, having time to think and dream, and possible shifts in his practice.

NPCould you tell me about the title of your exhibition, How High the Moon?

SWIt comes from an Ella Fitzgerald record, which my mother had. I liked the idea of continuing or always reaching for something, which it references. I think Ella once forgot the words during a performance of the song in Berlin, but she kept going anyway. I liked that whole idea. If a title feels good, I leave it. That's kind of the way I work too—I just go with it.

NPAre there particular combinations of works in this retrospective that you're excited to see for the first time?

SWIt'll be interesting—kind of like meeting old friends. Retrospectives allow an artist to look back and think about the decisions they made. It gives me time to ask myself, 'Why did I make that shift?' It's also a bit odd to look backwards because I'm always working—I'm working in the studio right now. Looking at earlier work will cause me to reflect on what was happening politically, or what I was thinking at that time. It'll be interesting to get a sense of whether I want to circle back and pick something up, or whether I am happy where I am currently.

NPYou were born in Philadelphia to family not particularly interested in art. When did becoming a working artist first seem feasible?

SWI was always the artist in the family. I always drew. But I also felt I had to wait to get out of high school to really start my life as an artist. I wasn't really a good student. It was the fifties, so it wasn't a great time for Afro Americans. Particularly for women, it was a difficult time. I went to a predominately white school where they integrated the small Black community—there were maybe ten Black kids in the entire school. I didn't adjust well to that environment at all.

I thought I could illustrate album covers. There were a lot of illustrations in magazines and newspapers. But I didn't know much about art at all. I went to the Philadelphia Museum of Art once. My parents were very good in terms of not getting in my way, but they didn't know what I was doing. I didn't know what I was doing either. I lived in Philadelphia, but I went to art school in Columbus, Ohio. I'd really wanted to go to New York, but there was the problem with the [U.S. military] draft, which had a big year when I got out of high school in 1964. It took me a while to figure things out.

NPYou've been candid about the hardships you've experienced in trying to make a career in art. You don't flinch from sharing financial struggles, needing to pay your rent, and so on. What's it been like to have this late-career success, and what has the recent focus on your work meant to you?

SWWell, I always tell people the stars line up when they line up. Sometimes success has to do with not just you but the rest of the world. I think about that in terms of someone like Ed Clark, who didn't see his success. Or Jack Whitten, who saw some of his. But you know, these were artists who were going to make the art regardless of success. I realised this about art early on because it was that important to me.

I'll go where the work takes me. I always tell people if it goes out the window, I'll follow it.

Luckily for me, I came from a family where things were difficult all the time, so I could handle my struggles. But a lot of people from my neighbourhood who were more talented than me didn't survive that situation. I'm happy for the success; it's been wonderful.

NPThere are some discernible shifts in your body of work. You stopped doing figurative painting fairly early, moving into abstraction. Could you share a little about that?

SWWhen I was in school, I loved to go to museums to see works by Munch or Cézanne or Velázquez and see how they made their paintings. I did a lot of self-portraits when I was learning how to paint and what paint was. Then one day it kind of died on me. I mean, I just arrived at a dead end. That was maybe during one of my last years in undergraduate school. And then I saw some Morris Louis paintings, which were these poured colour paintings, and I really loved them. I knew I could always make my work better with colour.

From 1968 to the late 1970s I was trying to figure out what I was going to paint and what my subject matter was. I was lucky that I had the time to figure it out. I can say 'lucky' now, but at the time no one was interested in the work. I would go see a lot of art when the galleries moved downtown [New York City], and ask myself, 'Do you want to do this?' And then I'd go back to my studio and do whatever it was I was doing, even though there was no success. Some of my colleagues had early success and then petered out. What I was doing wasn't very fashionable at the time.

NPYou often use a term to describe your practice that I love: 'dream time'. Can you unpack that and explore how it helped shape your career?

SWIt's about being left alone; being able to experiment and try things out. For example, with young artists coming out of art school today, you see this situation where if you're good, galleries take you right away. The problem is with developing your work, because once the work is out there it's difficult to make any shifts. It's like changing your clothes in public.

Dream time is really being able to work without knowing that they can sell your work for a lot of money.

You see what happened to Philip Guston. People start asking, 'Can you do that?' Dream time is really being able to work without knowing that they can sell your work for a lot of money. I had the time to just be involved with my own work and not have someone saying, 'Oh, I want that', or 'that's a good one', or 'I want you to do more of these.' I could dream about what I wanted to do or be.

NPWas it a lonely or isolating experience being a Black abstract painter in the 1970s? Who were your associates in those days? Who were you in conversation with?

SWThe generation ahead of me included Ed Clark, Jack Whitten, and Bob Thompson, who died before I got to meet him. But it really wasn't like there was a group of us in conversation. I mean, everyone was kind of on their own. Everyone was struggling. No one really had time to help someone else. When I got to New York, I invited guys like Alvin Loving and William T. Williams to my studio, but they were like, 'Hey, I'm struggling, too. Good luck.' So, you couldn't really complain or expect people to help you out.

At the time, the art world in New York was very small. When I got there, the minimalists were there. Barnett Newman was a focus at the time and then everyone went against painting. So, we were all struggling as painters. But at the same time, there were always parties and a lot of stuff going on, people gathering around—a very bohemian lifestyle. There was some relief in that kind of thing.

NPLet's talk about colour. You are interested in the connections between sound and colour, and you reference jazz quite a lot. Could you talk about colour and how it might relate to music? I'm thinking of that great story about the legendary jazz drummer Elvin Jones, who once said he thought of yellow when he heard cymbals. Is this similar to how you think of colour?

SWNo, I don't think of it that way. As you know, I came from a small Black community outside of Philadelphia, so music was always there. You'd go to bed with the radio on and you'd wake up with it on. Someone in the neighborhood had a Thelonious Monk record, and then I heard Eric Dolphy and Ornette Coleman. That's when I discovered what I wanted to do and how I wanted to think.

When I was in art school, I went to this little museum that had a Cézanne, and when I looked at it, the rhythm of it felt like Charlie Parker. I could see it in terms of the rhythm, not the colour. It was really about the rhythm. It took me a long time to figure out how to work with paints and what to do with colour. When I saw Frank Stella and Barnett Newman in New York, I didn't think much of what they were doing with colour. It seemed like decorative colour to me. I wanted to work with colour in a way that had more meaning, weight, and depth.

NPYou've given your grid paintings some interesting titles, particularly within your 'No to Prison Life' series. I've noticed you make pointed comments about race and politics in your interviews, but the works don't directly take up these topics in an obviously visual way.

SWWell, I don't illustrate. The works try to open up thought. It's like thinking about having a great piece of art in your house that you live with and contemplating how it feeds you, how it opens up what's possible, how it gives you courage, and how it allows you to think about what it means to be a human being. So, it's more about that.

The titles became a way for me to express another way of seeing who I am and where I come from.

The titles are there because most of my early works didn't have titles. Over time, the work started to come together with the politics. It was all coming together—the politics, the space—everything sort of came together. The titles became a way for me to express another way of seeing who I am and where I come from. They become a kind of diary of how I'm thinking and where I'm coming from. But there are so many ways of becoming involved with my paintings.

NPTell me how you arrived at the 'No to Prison Life' series.

SWThat came out of a book I was reading on Attica [prison uprising in New York]. I was in graduate school when Attica happened in 1971. I thought I had a sense of what that was all about, but the book really opened that up for me. It got me thinking about what it would mean to not see the night sky in over 20 years or forget what green grass looked like. I really do think they're trying to kill us off in prisons.

I don't title the works until after they're done. It gives me another way of talking about the work.

NPI know you're somewhat uneasy with the idea of a retrospective when you're still very much thinking and working. But are you sensing you might make any shifts in direction, or do you see yourself staying with the grid paintings?

SWWhen I was young, I saw a Mondrian show at the Guggenheim and at that point I wasn't even an abstract painter. But I loved how you could see how he built his body of work, step by step. He didn't miss a step. I loved how he moved. And I thought, 'That's the way I want to move.' I'm always drawing and I have different ways I go about it, whether it's the paper or the colour, or pencil or watercolour. The paper sometimes tells me what to do with it. I have lots of different possibilities, but I don't know what's next. That's an open question.

Maybe with the retrospective, I might be inspired to go back and reinvent or make the work more open. I've been thinking about de Kooning's late paintings, and how he made that shift. I've also been thinking about Guston, and wondering if he had lived longer, would he have had another shift? I really don't know. I'll go where the work takes me. I always tell people if it goes out the window, I'll follow it. —[O]