Art Encounters Biennial in Romania Finds Meaning in Disjunction

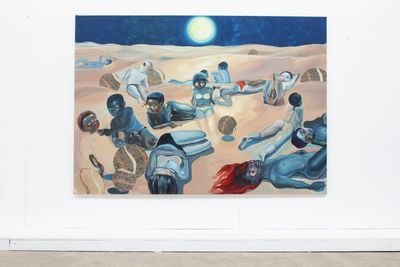

Exhibition view: How To Be Together, 4th Art Encounters Biennial, Timișoara (1 October–7 November 2021). Courtesy Art Encounters Biennial. Photo: Adrian Câtu.

Our Other Us, the 4th Art Encounters Biennial in Timișoara, Romania (1 October–7 November 2021) arrived at a time of crisis, opening as city-wide lockdowns and evening curfews were introduced in response to escalating Covid-19 infections across Romania.

Deftly, organisers adapted planned programming—events were changed to be outdoor where possible—and the Biennial has proceeded smoothly, and with proof of double vaccination status, international artists and visitors are still permitted to arrive.

This year's edition includes exhibitions and events across 16 venues and performance sites in Romania's third most populated city, located in the historically contested and multilingual Banat region, close to the Serbian and Hungarian borders.

Since the Biennial's first iteration in 2015, the city's investment in culture has continued to increase, no doubt influenced by the anticipation of Timișoara becoming European Capital of Culture in 2023. This year alone saw the opening of FABER Timișoara, an independent cultural centre, and the publishing of ARTSENS, the city's first art newspaper.

Continuing a precedent for two invited curators per iteration (in 2019, it was curated by Maria Lind and Anca Rujoiu), Our Other Us was organised by Mihnea Mircan, previously artistic director of Kunsthal Extra City in Antwerp, and Kasia Redzisz, soon-to-be artistic director of Kanal-Centre Pompidou, Brussels.

Perhaps surprisingly, this was not a creative collaboration but a bridging—an encounter, if you will—of two separate curatorial projects. 'There was never any attempt to cohere or to converge,' Mircan told Ocula Magazine. Rather, the Biennial has been 'constituted in their disjunction.'

Mircan's curated section, Landscape in a Convex Mirror, the title of which draws from Parmigiano's painting Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror (1524), departs from the shared subjectivity induced by the pandemic. As the curator is currently residing under lockdown restrictions in Australia, his exhibition was curated remotely, motivating Mircan to convey sensibilities of 'distance, anamorphism and vertigo'.

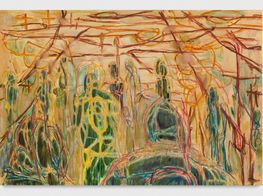

Works on view construct a dream-like, lucid, and sometimes violent sense of paranoia, beginning directly at the entrance, where Szabolcs KissPál's Silicone valse (2009), an open window installation with shattered glass panes, hangs on the wall.

Equally eerie are Jonathan van Doornum's simultaneously anthropomorphic, sterile, and tortuous sculptures distributed throughout the ground floor, including Untitled (TV antenna) (2017) and Tea Towel Rack (2018). Pre-modern and dystopian, they look like pieces of medical equipment intended for unsavoury surgical purposes, pairing well with Zsófia Keresztes's sculpture Smallest in Common (2019), where—in an almost sadomasochistic nature—cables bind and constrain biomorphic tentacular mosaic forms.

'The pandemic was an occasion for an accelerated shift into a calamitous direction,' says Mircan, and in keeping, disturbance, repetition, and parody are devices utilised by many artists in the show, such as Hito Steyerl, Achraf Touloub, Laure Prouvost, and Ana Prvački.

Critiques of consumerism and an increasingly embedded relationship with technology appear throughout. Sara Culmann's mockumentary Cargocento (2015–2021) imagines screen resolution as tomorrow's biggest indicator of quality of life and class. 'High resolution is cheaper than high life,' the film gleans with a wink.

The exhibition venue adds to the uncanny sensibility. Part of a 50,000-square-metre new development, the vast, empty concrete and glass ISHO Office 3 Building—conveniently owned by Ovidiu Şandor, CEO of a powerful local development company and president of the Art Encounters Foundation—has the strange feeling of a commercial building unsettlingly vacated during the pandemic.

Considering the show in relation to the Biennial's title—Our Other Us—the presentation certainly conjectures an innate desire to flee from forced and sometimes arbitrary restrictions.

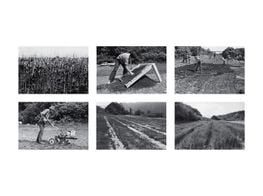

Across the courtyard is the smaller of Redzisz's two shows, Seasons End: Artists and Nature in Eastern and Central Europe 1965–85, located at ISHO House, which presents an alternative story to the now well-rehearsed Western canon of environmental and land art.

Contextualising known figures such as Agnes Denes with Romanian practitioners and collectives, Redzisz highlights radical works that were concurrently made across the landscapes of Eastern Europe, as they were in the United States.

'Artists had to find other spaces of freedom in the landscape to escape restrictions of the communist regime,' artistic director Diana Marincu elucidates, reflecting the government's disdain for avantgarde art practice at this time.

A display of framed documentation reveals the colourful happenings of the Timișoara-based Sigma Group (1969–1978) who staged experimental summer camps in the wilderness, departing from Bauhaus philosophy and the pedagogy of Buckminster Fuller.

While in photographic documentation of Károly Halász's provocative Hommage for Robert Smithson (1973), the artist sets petrol alight within a snaking trench shaped to resemble Smithson's iconic Spiral Jetty earthwork from 1970.

Considering the show in relation to the Biennial's title—Our Other Us—the presentation certainly conjectures an innate desire to flee from forced and sometimes arbitrary restrictions.

Although not explicitly linked, How To Be Together, Redzisz's larger contribution located in the vacated, post-industrial Public Transport Museum, is an apt counterpoint to both its historical sibling and Mircan's show.

Largely featuring a younger generation of artists from the region, including new commissions, Redzisz looks 'to present proposals for meaningful co-existence in the world.'

Dardan Zhegrova's commission A way of pretending that I can fly, I cannot (2021) is a floating, glistening mechanical sculpture resembling a dragonfly: a coded celebration of the artist's queer, non-binary identity.

Differently, Hana Miletić's vibrant array of abstract hanging sculptures, produced by migrant women living in Brussels, highlights the community-building power of craft as a non-verbal form of communication (Felt workshops, 2018–2020).

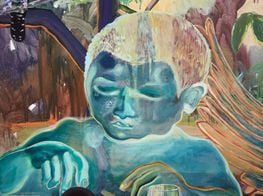

While Jura Shust's film Neophyte II (2019) explores the wilderness as a place for experimentation and shelter for lost generations of youth, Ndidi Emefiele's monumental painting Rehearsing Death (2020) depicts a youthful group sunbathing under a cool blue. It is unclear whether figures are in a state of calm, resignation, or ennui.

Wandering the show, writer Krisztián Török's postulation on Art Encounters in 2019 came to mind: 'What gesture does a biennale mean in Banat?'

These concerns are undoubtedly important when understanding the motivations for such a costly artistic project, especially in the tumultuous context of an ongoing pandemic. An impromptu encounter with city mayor Dominic Fritz, put rest to some of these concerns.

Fritz recognised Art Encounters as part of 'a wave of change that cannot be stopped.' As an institution, he noted, 'it understands that transformation is not just a political process but a spiritual one', and is 'making a conscious effort to mediate what contemporary art means ... by bringing young people to the event.'

Whether by chance or intention, it was interesting that the site of Redzisz's exhibition also functions as a Covid-19 vaccination centre, with the potential benefit of drawing more diverse groups to the exhibition.

Intersections continued at the satellite project Oasis. Green Identity at the Young Naturalists Resort (17 September–17 October 2021), where I observed children playing amid and with outdoor artworks, including Liliana Mercioiu Popa's expanded hammock Place for Doing Nothing (2021).

Situated on a working farm and horticultural laboratory on the outskirts of the city, Green Identity evidences an independent local commitment to ecologically minded practice. Curated by Maria Orosan-Telea, the exhibition features site-specific works by local artists from the Avantpost group, the first in the city to devise an exhibition confronting climate change back in 2014.

Among them is Oasis Radio (2021), an installation by Ciprian Chirileanu comprised of interconnected potatoes converted, with the insertion of zinc and copper, to generate electricity. The resulting 'semantic noises' (radio signals generated by the reaction) were amplified on speakers; a joyously absurdist potato symphony.

Another standout satellite commission at the centrally located non-profit Helios Art Gallery, is Carrier (2021) by Irena Haiduk. The installation showcases 'Yugoexport', an enterprise—part studio, part shop—that draws its conceptual and aesthetic identity from the communist factories and commercial corporations of the former Yugoslavia.

Engraved on a table made of decadent marble, resembling the palatial aesthetic of the U.S.S.R.'s Moscow Metro in Russia, are probing texts that speak to Art Encounters' search for meaning in disjuncture.

One orotund query particularly resonates: 'Do you think yourself lucky for being so hard, heavy and still? Do you wonder what it would be like if you could move?' —[O]