In Italy, Panorama Presents New Exhibition Possibilities

An hour northeast of Rome, on the hillsides of the Abruzzo region, sits the city of L'Aquila, fortified by mediaeval walls, where Baroque and Neoclassical structures lining narrow streets lead to resplendent piazzas. It is an unexpected, but striking place to find contemporary art embedded within the city's urban fabric.

Exhibition view: Luisa Lambri, Panorama L'Aquila, Italy (7–10 September 2023). Courtesy ITALICS, the artist, and Thomas Dane Gallery. Photo: Luca M. Fontana and Alessio Tamborini.

Curated by Christiana Perrella, the third edition of the city-wide exhibition Panorama (7–10 September 2023) attracted a significant crowd to L'Aquila last week. The event exemplified how gallery networks and local communities can work together to support the preservation of heritage while expanding the boundaries of exhibition-making.

Supported by UNESCO and Italy's Ministry of Culture, the yearly exhibition is organised by a partnership of over 60 Italy-based galleries, including Galleria Continua, kaufmann repetto, and Mazzoleni. Their plein-air presentation offered a refreshing contrast to ticketed fairs that opened in New York and Seoul the same week under Frieze.

L'Aquila has long been a centre of exchange, trading in raw materials such as saffron and wool, where religious ritual and artistic patronage abound. The Academy of Fine Arts, founded in 1970, has earned itself a reputation as an avantgarde institution, where students benefited from the teachings of instructors such as post-war artist Fabio Mauri.

Under golden sunlight, locals and visitors explored 20 locations, from historic churches and ornate palaces to homely bakeries and record shops, where works by some 60 artists were installed to show the 'regenerative power' of art on society and urban environments. Together, they cast light on the city's fragile but significant heritage, which has lived through cycles of destruction and re-birth throughout the years.

Indeed, remains of the earthquake that devastated L'Aquila in April 2009, the worst Italy had seen in 30 years, with over 300 casualties, are noted all around—from abandoned buildings and abundant scaffolding to the city centre itself fenced-in pending reconstruction. It is where a thousand art historians rallied in 2013 to urge the government to restore the city.

This responsibility of renewal trickles down into the cultural realm. Starting at the city's entrance, artist Alberto Di Fabio's mural depicts chaos and creation in the universe with earthquake debris. The swirling monochrome patterns in Enigma della Materia (2023) evoke a process of alchemic concussion, hinting at the possibility of new beginnings.

A small trek uphill, a 4.5-metre-tall mammoth skeleton found outside L'Aquila in 1954 opens the show at Museo Nazionale d'Abruzzo, a 16th-century Spanish fortress occupied by the Nazis during World War II. The fully preserved animal is complemented by artists Radha D'Souza and Jonas Staal's musical video Comrades Against Extinction (2022).

This harmonising of old and new to bring out distinct resonances throughout time is something Panorama does particularly well. Massimo Bartolini's In a Landscape (2017), for instance, plays a composition inspired by John Cage at the centre of a Baroque church. A small organ connected to concert chimes emits a soft melody inside a brutalist well.

Additional sound performances, film screenings, and discussions with artists over coffee further enlivened the four-day event. Visitors queued to see artist Darren Bader's band perform an oddly compelling blend of classical and rock music inside a compact space supported by metal scaffolding. The room could only hold eight people at one time, all of whom were given construction helmets before entering.

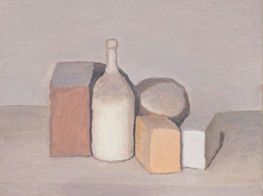

Modern and contemporary congregate at Palazzo de Nardis, where Giorgio Morandi's beautiful still-life drawing Natura morta (1948) and Lucio Fontana's crucified Gargoyle overlooking a prayer bench (Crocifisso, 1954–1955) are among the highlights.

Inside a reading room, two distinct vases by David Monaldi rest on a wooden table in surprising harmony with their environment. One presents an apocalyptic scene of tangled monsters, demons, and bodies (BAGARRE, 2023), while the other has its surface entirely covered in tiny, outstretched bats with pastel-pink genitals (Ravers, 2023).

Local gelato shops begin to fill around five, with many gathered around Caffé Fratelli Nurzia's window display hosting Alek O.'s pastel sculptures made of sugar paste. Its radical title, Il giorno della fine non ti servirà l'inglese (On the final day you will not need English) (2023), speaks to the adoption of politically autonomous positions and sustaining cultures made to last.

This spirit is shared by Pascale Marthine Tayou's The Spirit of L'Aquila (2023), a translucent quartz totem filled with bright crystals and surrounded by more gemstones scattered on the ground. The whole glimmers at the centre of the cream-coloured colonnade courtyard of Corte dei Conti, an auditors' court.

At the unfortunately damaged Palazzo Rivera, where the majority of works congregate, a monumental green ink-dyed canvas by Tatiana Trouvé recalls ghostly apparitions mid-forest, while Vincenzo Schillaci's Phàntasma #20 and #21 (both 2023) present harmonious blends of pigments with quartz and crystal powders, resulting in overlapping layers of primary colour that greet the eye like a whisper.

In casual conversation, a local elderly man shares that none of the works particularly resonated with him. He asks a common but unspecific question—whether contemporary art is art, from which a second question arises: whether these site-specific artworks must give up something of their own to integrate and support their immediate environment.

Until now, this kind of city-wide exhibition, which enacts a social and environmental conscience, remained mostly within the purview of the biennial exhibition and its ambitious curatorial statements. Similarly, at Panorama, artworks posed subdued statements, turning the spotlight towards the city's landscape, history, and architecture instead.

Back in 1967, Italian art critic Germano Celant introduced the term Arte Povera to describe a movement of young artists who protested the commodification of art and increasing industrialisation around Italy by making sculptures and assemblages out of mundane, costless materials such as soil, stones, clothing, and rope.

To reach audiences beyond conventional art galleries, they exhibited in warehouses and public squares and used their work to address social inequalities and injustices at times of student protests and labour strikes. Importantly, they reminded viewers of art's capacity to connect people, inspire ideas, and start discussions.

This sentiment was felt in L'Aquila last week, where artists, gallerists, curator Perrella, and local businesses created a space for discussions and gatherings, and art and resources were leveraged to support the restoration of a locality and cultural memory.

Panorama, while still a local affair, intends to gradually expand its commitment to create more gallery alliances. From this, perhaps new exhibition models can emerge, positioning gallerists as more than merchants, but active contributors to the wider cultural spheres in which they are embedded, both locally and globally. —[O]